Introduction

Global corporations are sophisticated institutions, which organize their business with the goal of delivering value to their different stakeholders. To permit quantification and exchange of such value, financialization becomes important. Diverse views exist on how and the manner in which multinational and national corporations have evolved to take their current configurations where they operate as economic institutions (Dore 2008). Amid the varied explanations of the evolution process of modern organizations, businesses can be analyzed and explained in terms of different processes that serve the function of economization of organizational transactional costs. Other issues such as quests for gaining organizational monopoly and the adoption of technological savvy may also explain the operations of national and multinational corporations (O’Sullivan 2001). This claim suggests that power constitutes an important factor in determining the influence of an organization in the international domain.

Corporations need to measure their effectiveness, their degree of influence in the international arena, their economic performance, and corporate governance among other crucial operations elements. Thus, an instrument for measuring all these aspects to allow comparison with other corporations is necessary. The development of financialised performance indicators constitutes a common instrument for measuring almost all performance indicators. This paper claims that the need to develop a means of measuring various aspects that define the operations of today’s corporations has led to the emergence and development of the concept of financialization. The main objective of this paper is to conduct a critical analysis of the concept of financialization and its usefulness in understanding today’s economy.

Defining Financialisation

There is no scholarly agreement on the precise definition of financialization. Over the last three decades, global money matters have undergone massive transformations. In particular, the contribution of the government in regulating economies has incredibly dwindled. This situation has led to the emergence and subsequent growth of free markets (Dore 2008). Indeed, there have been increasing financial transactions among nations, domestic corporations, and multinational corporations. These developments are associated with the growing globalization of organizations, the development of neoliberalist approaches in organizational operations, and the increasing financialization (Dore 2008, p.1099).

Different scholars describe financialization without establishing its precise definition. For example, Kripper (2004) only offers a historical background of financialization. He describes its impacts without defining them. Some writers deploy the term to imply ‘ascendancy of ‘shareholder value’ as a model of corporate governance; some use it to refer to the growing dominance of capital market financial systems over bank-based financial systems’ (Kripper 2004, p.12). Dore (2008) asserts that financialization implies the rising deployment of both economic and political powers to create people of diverse classes. This observation suggests that financialization denote the amplified deployment of financial instruments in executing financial trade across the globe. According to Kripper (2004), it means profit accumulation through both national and multinational trading via various financial channels as opposed to increasing financial capacity via commodity production. This description of financialization implies that the concept does not require the production of commodities and their trading in free markets for any organization to increase its financial resources. Rather, financialization also occurs due to trading in non-tangible financial instruments such as securities, government bonds, and economic rents.

The above description captures some, if not all, issues that underlie the concept of financialization. This paper adopts Epstein’s (2009) definition of financialization. The scholar defines it as ‘the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors, and financial institutions in the operation of domestic and international economies’ (Epstein 2009, p.3). Although not all economic scholars can agree on this definition, the implication of financialization in understanding today’s economy is sound. Indeed, financial motivates for corporations and financial institutions are critical in controlling the current world economy. Financial actors regulate the inflow and outflow of resources into the global free-market economy. They create surpluses or deficits.

Financialisation and the Increasing Effectiveness of Financial Economies

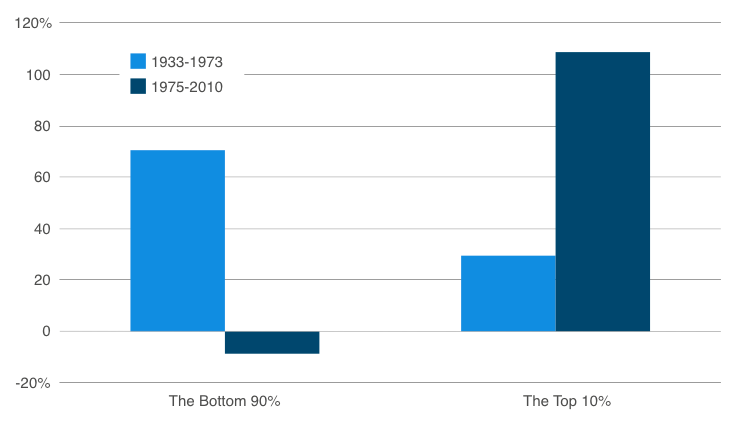

After 30 years following the Second World War, the US emerged as a middle-class economy. The nation’s poverty levels were reduced by nearly half. The economic scholars deployed the term economic great compression to describe this phenomenon (Turbeville 2015, p.1). As shown in graph 1, the great compression had the ramifications of increasing disposable income among the 90% of the American households. At the same time, inequalities in wealth among US citizens were at the lowest ebb.

In more than three decades after the great financial depression, economic gains for the majority of low earners was reversed. Indeed, over recent years, the largest percentage of the US households has encountered little, and in some cases, absolute zero gain in their real income. On the other hand, the least populous and the richest groups of the American people have been experiencing continuous growth in their real income. Indeed, between 1992 and 2012, 1% of the US population gained 70% of the total income increment (Saez & Piketty 2003). This situation has transformed American society into the post-great compression era. These changes have been accompanied by different structural alternations. For example, in today’s US economy, tax codes are much less progressive with weak labor unionizations, which hinder the struggle for equality in salary and wage allocation (Johnston 2005). The private sector has also become increasingly strengthened. The implication has been making the rich population segments richer. The reasoning behind such changes is that market liberalism and the adoption of the principle of higher capital allocations are the fairest mechanisms of running an economy. However, the 2008-2009 financial crisis perhaps taught something different. The Financialisation of the economy to permit the existence of unregulated free markets is an infeasible economic model.

Before the onset of the global financial crisis, the major economic debate in the US surrounded the need for mitigation of financial risks. There was particular concern over the increased exposure of financial institutions to financial risks. This case culminated in the enactment of Dodd-Frank legislation in 2010. Now, the major debates and concerns of economic scholars are on the role of financialization of virtually all economic systems in today’s economy and the risks that are likely to arise from the move.

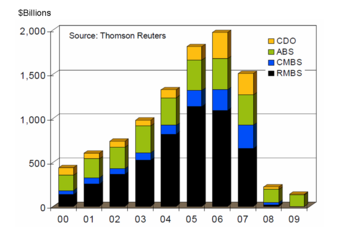

The global financial crisis, blamed on increased financialization, increased susceptibility of economic systems to credit risks. This form of risk encompasses the perceived risks by investors. It accrues from the failure of borrowers to make payments as agreed. Precisely, credit jeopardy denotes the danger of failing to attain a monetary remuneration following a borrower’s letdown to reimburse a credit or otherwise fulfill a contractual responsibility (Cornett & Saunders 2006). The risk has negative ramifications since some structures of a financial organization may collapse in totality upon the occurrence of a financial crisis. For example, as depicted in graph 2, the 2007-2008 global financial crisis influenced severely the US securitisation markets.

In the context of the European nations, financial institutions borrow money from superfluous expending bodies, namely the SSUs, and then loan it to arrears expending bodies, namely the DSUs. SSUs put their funds into the financial institutions that anticipate securing a preset amount of profits on their funds. They also anticipate being immune to various risks of investments. Eken, Selimler, and Kale (2012) claim that DSUs make efforts to borrow money from the banking industry in an effort to fix costs that relate to their borrowings. They also aim at protecting themselves from potential risks that arise from an imminent financial crisis. Such an effort is pivotal in ensuring that DSUs and SSUs deal with financial uncertainties. During the global financial crisis, SSUs and DSUs pushed banks to assume unwanted risks in the EU banking system. Consequently, financialization had the implication of increasing exposure of the financial institutions to unprecedented risks in the quest to make high gains. Indeed, today’s economy can be interpreted as an economy of increasing exposure to risk with expectations of high gains in the future.

In today’s financial systems, through strategies such as providing customers with various intermediations, banks acquire certain risks, which customers do not want. Consequently, one of the major concerns for banks is to manage their risks in an efficient way in the effort to gain returns on investments whilst protecting their shareholders’ equities. This goal is realized when there is financial prosperity within different countries. Increased financialization exposes financial institutions to major threats in their effort to mitigate risks and/or increase their profitability and market value. However, although high financialization may lead to a financial crisis, it is important to note that the financial crisis influences economic systems differently depending on their risk resilience capacities. Sensitivity and volatility constitute the building blocks of financial risks in the case of risk-prone banks. Such banks have high levels of sensitivity and low levels of volatility. This situation implies that during the global financial crisis, risk-prone banks experienced negative effects in a more severe manner than the risk-averse banks.

Borrowing from the global financial crisis experience, increased financialization has the ramification of raising volatility levels. The 2007-2008 situation had the implication of shrinking investor preferences in terms of ignoring the associated risks (Eken, Selimler & Kale 2012). In such situations, risk-prone investors also make strategic decisions to deploy risk-averse strategies in the effort to keep exposure to non-financial and financial risks at the lowest levels. To this extent, De Haas and Van Horen (2011) assert that the financial crisis forces economic-financial systems to raise their efforts to conduct a thorough scrutiny of the borrowers to ensure that they eliminate the risks of loan defaults. Ivashina and Scharfstein (2010) support this assertion by adding that banks reduce their lending activities during a global financial crisis. For instance, during the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, the largest decline in lending occurred for banks that had had low accessibility to financial deposits.

Financialisation implies increased financial transactions that characterize today’s economy. However, economic scholars describe the term differently, although they indicate its role in devastating the global economy. Turbeville (2015, p. 5) describes financialization as ‘the transformation of one dollar of lending to the real economy into many dollars of financial transactions. Dore (2008) describes it as the mounting significance of monetary management as a basis for getting income in the fiscal system. However, such descriptions may not provide a clear understanding of the concept in terms of how it increases the effectiveness of the financial sector. The principal role of financial systems entails the intermediation of capital flow in an economy. Financialization controls the flow of money and the transfer of risks (Turbeville 2015). Capital intermediation operates as the key indicator of the desired directions of today’s economy through strategies such as investment prioritization. Institutions that increase the living standards of a country as opposed to the accrued remuneration fail to guarantee fair and resourceful capital allocation in favor of the community. Unfortunately, this turned out to be the effect of increased financialization in the 2008-2009 period.

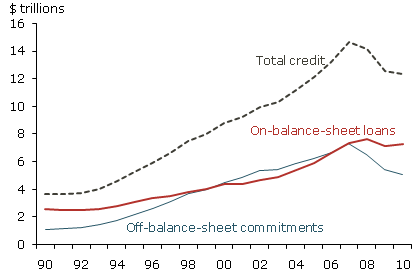

Financial organizations provide liquidity to creditors and/or depositors by putting in place programs for giving money on demand. Liquidity risk arises from outflows in deposits and the process of making lending arrangements between banks and other associated financial bodies (Barajas et al. 2010, p.13). Such arrangements consist of any pending credit dedication and the requirements to acquire securitized property. Banks lend money by developing credit lines on which the borrowing people tap after declaring their commitment. When borrowers take advantage of the available credit services, banks are exposed to higher financial risks. In fact, the falling supplies in liquidity compel borrowers to massively draw money in the form of credit from accessible credit lines (Eken, Selimler & Kale 2012). During the 2007 to 2008 financial crisis, the non-financial sector organizations had no access to short-term loans, following the drying up of the commercial paper markets. People who utilized the commercial paper resorted to prearranged credit lines from the bank to help them finance their paper whenever necessary. Since financial institutions had the responsibility to subsidize the credit, funds that were available for lending became incredibly limited. To help in stimulating the economy, the government considered deleveraging the economy, which resulted in high financialization.

Financial institutions sponsor their balance sheets in varied ways. Some of the most important ways are fair play investments and deposits, wholesale of uncovered deposits, and reacquiring of unprotected contracted equipment. In the condition of a monetary emergency, as evidenced by the witnessed international monetary catastrophe, these interventions became limited. For instance, repos were used in financing highly risky assets among them the ‘private-label mortgage-backed securities’ (Eken, Selimler & Kale 2012, p. 25). According to Gorton and Mentrick (2011), by the middle of 2007, all these securities were possible to fund through short-term loans that were acquired from the repos.

Upon the occurrence of the large-scale economic catastrophe, the above approach was transformed. By the end of 2008, only about 55 percent of all such securities were possible to fund from repos. Consequently, financial organizations that deployed repos to finance themselves encountered unattractive choices (Eken, Selimler, & Kale 2012). Hence, they suffered huge losses, as the only available option was to sell securities in a collapsing financial market. Increase financialization may lead to escalated liquidity risk, which is a key component of today’s economy. Graph 3 below depicts the impacts of liquidity risks on the US financial institutions.

Financialisation has driven and fostered incredible growth of the US financial sector. Nevertheless, this achievement only accounts for one side of the whole picture. While it has transformed today’s economic-financial sector, it has also had the ramification of the non-financial sector, including households, which have now been integrated into today’s financialised economy. Major non-financial businesses operate under the influence of the stakeholder theory, which insists on the necessity of engaging in socially responsible conduct. The stakeholder theory directly relates to the concerns of financialization. CSR principles, which characterize the activities of major organizations that operate in today’s economy, make them operate as hedging fund entities where their performance is determined by the market share value, which is expressed in financial terms (Aguilera & Gregory 2003).

In the case of households, financialization influences them directly. For example, the financialization of retirement securities has a direct impact on individuals and US households. Krippner (2004) supports this assertion by claiming that individuals continue to experience the implications of financial market dynamics via market manipulated issues such as retirement savings. Some people even wish to reach the extent of influencing public defense savings alternatives. Whether this strategy is the most effective way of controlling social security in the US or not, financialization is a real characteristic of today’s economy. Hence, it is critical to the understanding of modern financial systems.

The real estate bubble, which busted in 2007, leading to the global financial crisis, perhaps constitutes one of the best examples of the manner in which financialization defines today’s economy by controlling individuals’ and households’ investment behavior. Many people invested in mortgages above their capacity to finance them. They invested without control on the continuously increasing home values. They were encouraged to do so by financialised mortgage securitization bodies. Households and individuals retained large portions of leveraging derivatives for real estate. The implication of financialised mortgage securitization was damaging the US economy in a massive manner.

In today’s economy, education plays a critical role in availing skilled and knowledgeable labor forces to drive the production and service sectors as a way of yielding income to the economy. To understand how education functions in enhancing the performance of today’s economy, the concept of financialization finds a key position in appreciating the operation of education systems. In the US, there is a sharp decrease in state funding of post-secondary education. This situation has caused a sharp rise in tuition fees, resulting in a rapid increase in US student debts. Financialisation of education has the impact of making the US citizens analyze the importance of higher education through making comparisons of the expenditures in it and the anticipated financialised earning capacity. As opposed to the previous situation, the current financialization of education means that social gains from having an educated citizenry do not count in the equation of the contribution of education to the growth of the US economy. People are only interested in the current and future financial gains of investing in education.

Financialisation and the Dynamics of Capitalism

Financialisation refers to the reduction of all terms of exchange involving tangible, intangible, current markets, and even future market terms into some sort of financial instrument. This attempt corresponds to the characteristics of the modern economy that is characterized by increased calls to ensure the flourishing of free global markets. In the modern economy, there is a need to adopt a common formula for valuing tangible goods and services, intangible goods and services, and even future promises. This formula can act as a tool for measuring relative financial positions or the performance of one organization against the other.

In Keynesian capitalistic markets, organizations aim at outdoing their competitors (Crouch 2009). Businesses that are likely to succeed in the long term are those that are effective in building their competitive advantage. In today’s economy, this situation occurs when an organization can measure its performance and all its operational components under a common measurement tool, mostly financial values, which are expressed in terms of financial positions with respect to a dollar. Indeed, organizations that have a higher financial position have enormous corporate power (Gourevitch & Shinn 2005). This claim means that they can compel or influence weaker organizations to behave in certain ways. In today’s economy, various leading financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have the power not only to influence the conduct of other organisations but also different states.

Different approaches are deployed in building the competitive advantage of any organization that operates in today’s economy. Some organizations market their products through push-and-pull strategies, while others focus on pricing strategies among other tactics. For instance, in the airline industry, many organizations focus on price reduction strategies and/or building customer experience to freely compete in the airline operational routes. In open bazaars, organizations have the freedom to fix the cost of their commodities and services based on the concept of requirement and provision, but not through authorities, governments, or price-setting monopoly powers. These observations suggest that free markets differ from the controlled markets where ‘the government intervenes in supply and demand through non-market methods such as laws that create barriers to market entry or directly setting prices’ (Bockman 2011, p.105). However, in both the controlled and free markets, a tool is necessary to indicate the financial position and the relative performance of an organization in comparison with other organizations that operate in the same industry. Reducing all tangible, intangible, and even future promises of an organization permits the government to set ceilings for controlling the market. The move provides an organization with instruments for making vital decisions in free markets.

In capitalistic economies, private firms mainly own trade and factors of production. The businesses maneuver them to make the best possible returns. Capital accumulation, wage labor, and competitive markets characterize such economies (Gourevitch & Shinn 2005). Financialization is important in measuring capital accumulation and wage labor of such markets. In the capitalistic economy, parties that make trade transactions are involved in the setting of prices for exchanging assets and goods and services (Harvey 2014). Setting the prices is impossible without the financialization of all tangible and intangible inputs of the production process. The case of major airlines operators in Europe evidences that a reduction of all tangible and intangible goods and services and future promises into financial instruments is critical in making vital decisions in today’s economy.

The airline industry in Europe experienced immense government deregulation in the 1990s. This move was to ensure that the industry could solely set prices for its services in a bid to make the airline markets capitalistic, and hence competitive. In the airline industry, two types of capitalism can be differentiated, namely socio-market economy and the free-market economy. Open bazaar financial systems adopt an investment plan in which the cost of services and commodities are established by the monetary demand and supply rules. The forces are permitted to reach an equilibrium point without any intervention of the government in ways such as price control. A free-market economy fosters the development of competitive markets. It also encourages private ownership in a bid to enhance the existence of highly productive enterprises. Free markets manifest themselves in the airline industry through the permission of the organizations that operate in the industry to set their own prices without any governmental regulation. Prices are impossible to set without the knowledge of expenses and revenues generated by an organization. Making a relative comparison between revenues and expenses means that all aspects of an organization should be reduced to a common instrument; say a dollar or a pound.

A socio-market economy constitutes a free-market economic system in which government intervention in the control of prices is kept at minimal levels. In the airline industry, any government intervention manifests itself in the form of regulations on labor rights, social security, and employment benefits. With these regulations, the European airlines’ stakeholders make the final decision on the best prices, which help them to cover the costs that are imposed by the government to protect workers in the industry and/or make substantiated profit margins. To ensure that an airline industry covers its fixed and variable costs competitively, it must seek ways of becoming large enough so that it can take the advantage of economies of scale. Analyzing potential partners to form mergers or even acquisitions with players in the European markets reduces all assets and liabilities of potential partners into a financial instrument to determine the attractiveness of the likelihood of the partnership helping to build a competitive advantage.

Financialisation provides a mechanism for determining the effectiveness and efficiency of an organization. In today’s economy, efficiency and effectiveness imply more gains to all organizational stakeholders. The management of an organization cannot negate emphasizing increasing competitive advantage through increased organizational operational efficiency and effectiveness if it has to build the capacity to have a long-term performance. Failure to follow this path, organizations cannot even deliver optimal welfare to their employees. Such failure has the impact of lowering employee productivity due to low motivation levels.

In a capitalistic market, all stakeholders invest in activities that lead to increased personal capital accumulation (Harvey 2014). This plan implies that even employees in an organization are more motivated if the increased profitability of an organization that has employed them translates into increased personal gains in terms of higher salaries and wages. With the deregulation of the mergers operating in the European airline industry, each organization develops policies for increased profitability while employees respond to such policies by working harder to achieve higher gains in terms of salaries and commissions, especially in the case of air ticket vendors. Since the salaries received by the air ticket vendors depend on the number of sold tickets, such tickets should be reduced to a financial instrument to permit the calculation of commissions.

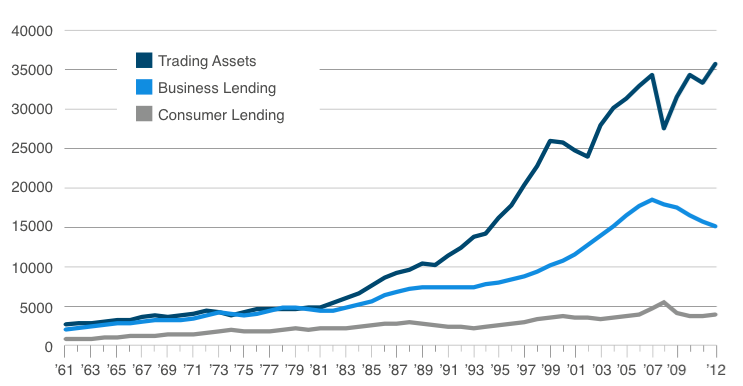

Financialisation explains almost all aspects of today’s economy. For example, via financial instruments, people acquire an opportunity to not only trade mortgages, but also future promises for homes. Financialising the anticipated risks leads to the creation of insurance firms. Through the financialising pledges by the administration via bonds, it becomes achievable to guarantee arrears expenditure. Economic rents rely on financialization. The disproportionate growth of financial institutions of the US economy over the financialization era occurred dramatically. Financialisation has occurred mainly in two major areas, namely capital intermediation and derivative trading. Intermediation of capital constitutes the main facet of intermediation. This plan has out-phased conventional lending of financial institutions. Through business, shares are availed to derivative bazaars in a bid to elevate new funds for organizations. Turbeville (2015, p.7) asserts that via secondary markets ‘previously issued securities are made available for purchase or sale on a relatively continuous basis at prices that are, to some extent, related to the widely accessible price signals.’ This claim means that financialization explains the creation of ancillary markets to various primary markets through securities and shares trading, which dominates today’s economy. Graph 4 below shows the increasing importance of assets trading and consumer leading due to financialization in today’s US economy.

Trading in secondary markets provides the pillar for capital intermediation. People who invest in the markets depend on the changing price signal as the basis for conducting evaluations for holdings. Liquidity defines the values of secondary markets. Without financialization, it would be impossible to provide capital intermediation in secondary markets that constitute today’s economy. Currently, rent grows exponentially in the US economy. Inferior bazaars act as an important supply of rent. Turbeville (2015) asserts that while derivatives grow by over 60 trillion US dollars every year, globally, financialization has made it possible to ensure more than double the growth of derivatives. The experiences of the 2007-2008 financial crisis indicated the importance of providing economic leveraging systems. To this extent, derivatives form important mechanisms for mitigating risks, as key determinants of the ability of governments to control their economies to prevent a sudden downfall.

Today’s economies are characterized by overleveraging. They possess more borrowed capital to run the economy compared to their capital. Overleveraging is an important aspect of financialization. To understand today’s economy, this concept suggests that understanding financialization cannot be negated. Some of the important derivatives that are traded in secondary markets entail swaps and future treaties among others. In the finalized markets, the richest portion of the population acts as the biggest gainer. This claim means that when financialization equations yield success, capitalism becomes the dominant force that controls many world economies.

Conclusion

Financialisation constitutes one of the significant features that mark today’s economy. Although financialization came into the scholarly limelight in the 1980s, its importance was recognized by most economists after the global financial crisis, which occurred in 2007-2008. The current economy evidences various features of financialization such as CDOs, securitization, and shadow banking. The implications of these features include high investments, rising inequalities, and instabilities. All organizations now express tangible and intangible items of trade and future promises using standardized financial instruments. Consequently, the claim that financialization constitutes the pillar for understanding today’s economy is sound. The current fluctuations of economic capitalism support the claim.

References

Aguilera, R & Gregory, J 2003, ‘The cross-national diversity of corporate governance: Dimensions and determinants’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 28 no. 3, pp. 447-465.

Barajas, A, Chami, R, Cosimano, T & Hakura, D 2010, U.S. Bank Behaviour in the Wake of the 2007–2009 Financial Crisis, IMF Working Paper, WP/10/131, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Bockman, J 2011, Markets in the name of Socialism: The Left-Wing origins of Neoliberalism, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Cornett, M & Saunders, A 2006, Financial Institutions Management: A Risk Management Approach, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Cornett, M, McNutt, J, Strahan, P & Tehranian, H 2011, ‘Liquidity Risk Management and Credit Supply in the Financial Crisis’, Journal of Financial Economics , vol. 101 no. 2, pp. 297–312.

Crouch, C 2009, ‘What Will Follow The Demise of Privatised Keynesianism?’, The Political Quarterly, vol. 80 no. 3, pp. 302-315.

De Haas, R & Van Horen, N 2011, Running for the Exit: International Banks’ and Crisis Transmission, EBRD Working Paper, no. 124, Routledge, London.

Dore, R 2008, Financialisation of the global economy. Industrial and Corporate Change vol. 17 no. 6, pp. 1097-1112.

Eken, M, Selimler, H & Kale, S 2012, ‘The Effects of Global Financial Crisis on the Behaviour of the European Banks: A Risks and Profitability Analysis Approach’, ACRN journal of finance and risk perspectives, vol. 1 no. 2, pp. 17-42.

Epstein, G 2009, Introduction: Financialisation and the World Economy, 2015, Web.

Gorton, G & Metrick, A 2011, ‘Securitised Banking and the Run on the Repo’, Journal of Financial Economics vol.104 no.3, pp. 425–451.

Gourevitch, P & Shinn, J 2005, Political Power and Corporate Control, The New Global Politics of Corporate Governance, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Harvey, D 2014, Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ivashina, V & Scharfstein, D 2010, ‘Bank Lending During The Financial Crisis of 2008’, Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 97 no. 11, pp. 319-338.

Johnston, D 2005, Perfectly Legal: The Covert Campaign to Rig Our Tax System to Benefit the Super Rich and Cheat Everybody Else, Portfolio Trade, New York, NY.

Krippner, G 2004, What is Financialisation? Mimeo, Department of Sociology, UCLA.

O’Sullivan, M 2001, Contests for Corporate Control: Corporate Governance and Economic Performance in the United States and Germany, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Saez, E & Piketty, T 2003, ‘Income Inequality in the United States (1913-1998)’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 1 no. 3, pp. 123-137.

Turbeville, W 2015, Financialisation and Equal Opportunity, Web.