Introduction

The interactions between dividends payouts and the effect this has on the stock prices is an issue that elicited mixed reactions amongst academicians and scholars alike. This is mainly because dividend impacts on stock valuation, in addition to tax policy, as they apply to the stockholders of a firm (Docking & Koch 2005). Ultimately, there is a spill-over of this interaction to the economy of a country, through the stock market.

The taxes that shareholders are normally subjected to upon receiving dividends payouts tend to impact the prices of a stock since such taxes usually gets imposed on the shareholder’s earnings, as well as the offloading of a firm’s shares by means of share repurchases, trades, and also liquidating distributions, in effect lowering an investor’s cash flows after taxation (Fama & French 1992). There is also compelling evidence to support the claim that dividend policy normally impacts the volatility of a stock market.

When a firm pays its stockholders large amounts of dividends, this helps to lower the risk that is associated with the firm’s stock price, in effect impacting the price of a stock. Moreover, such a development also acts as an index for a firm’s future earnings (Baskin 1989). Miller and Rock (1985), opine that the announcement of dividends helps to shed light on the lacking pieces of information regarding a firm.

In addition, dividend announcement gives room to the stock market to approximate the current earnings of a firm. As such, investors are best placed to gain more confidence in the announced dividends (Frankfurter & Lane 1992), and they may tend to buy more of these, as opposed to the investors of a firm that fails to announce dividends. The expectations of an investor also benefit from a cushioning effect against irrational fear. Nevertheless, there is a need to question the value attached to dividends issuance by a firm.

Payment of dividends ensures that there is a flow of cash to a shareholder, and a reduction on investment resources, on the part of a firm, and this may very well impact on the share of the stocks of such a firm. Thus far, numerous empirical and theoretical researches have been carried out to explore the effect that the payout of dividends has on the price of a stock (Hartono 2004). Hypothetically, cash dividend implies that shareholders receive rewards from the firm, in the form of cash. Consequently, the issuance of dividends shall more than be compensated for by a reduction in the value of the stock of such a company.

This research study is concerned with the assessment of the relationship that exists between dividends and stock prices. To start with, a description of dividends shall be provided, followed by the various types of dividends, as they apply at the corporate level. The various theories of dividend, such as the signaling, tax-adjusted, agency cost, behavioral and free cash flow models shall all be explored, as they apply to the corporate dividend policy. There is evidence in literature to support the claim that dividend policy usually has an effect on the volatility of a stock price. Consequently, this issue shall also be examined in depth.

There are several elements that affect the stock price, and these include the internal as well as the external factors of a firm. These have also been exhausted to great lengths. The various ways through which the prices of a stock are affected by dividend payouts have also been examined. In this regard the association between dividends and the value of the stocks of a firm is explored, along with the existing argument on dividends and tax.

Ultimately, several cases studies on the correlation between dividends and stock prices have been provided. These case studies have examined the stock markets in the United States, the UK, and the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) countries.

Dividend

Dividends refer to those payments that shareholders receive from the corporate in which they have a stake. According to Sullivan and Shefrin (2003), a dividend is that portion of the profit realized by a firm that is usually paid out to the stockholders of such a firm. At a time when a firm realizes a surplus in terms of earnings, or realizes a profit, the management of such a company has two options to utilize such monies: first, the management may decide to re-invent the earnings so realized, and such monies are usually referred to as retained earnings.

Alternatively, the firm may choose to pay out this money to its stockholders, usually in the form of dividends. A majority of the corporations chose to retain a certain percentage of the earnings that they make, and then decide to pay out the rest of the money to their stockholders in the form of a dividend (Lee 2006). In case of a joint stock firm, the allocation of a dividend is usually in the form of a standard amount for every share that a stockholder has in the firm in question. Consequently, the dividend that a shareholder receives is in tandem with the number of shares that they have in the firm.

Dividends payments are usually not regarded as an expense, in the case of a joint stock company, but are instead viewed as an act of distributing the assets of the company amongst the various shareholders (Lee 2006). For the public companies, the payment of dividends usually takes place on the basis of a fixed schedule. However, there is the possibility of a public company announcing the issuance of a dividend any time, in which case it is referred to as a special dividend, in a bid to draw a difference between this bond, and the regular one.

In contrast, the allocation of dividends by cooperatives is on the basis of the activity of the individual members. Hence, the dividends of a cooperative are usually viewed as ‘a pre-tax expense’ (Mukherjee, & Atsuyuki 1995). The settlement of dividends is normally on the basis of cash. However, there are other forms of issuing dividends, in the case of a cooperative, and these include company shares or store credits, a trend that has really gained popularity amongst the consumers of retail cooperatives.

Moreover, a majority of the public companies now provide reinvestment plans for dividends, and these automatically utilize the cash dividends for purposes of buying extra shares, for the firm’s stockholders.

Forms of dividends payments

Cash dividend

Cash dividends are usually the most common and normally, the mode of payment for this is through the use of a cheque. These dividends act as an investment income, meaning that they are normally subjected to a taxation exercise, at that financial year in which they are paid out. Cash dividend stands out as the most common technique that different corporations utilize ((Lee 2006), for purposes of sharing the profits that they make with their stockholders.

The declared amount of cash to be paid as dividend depends on the number of shares that a given shareholder owns. For example, for an individual who owns 100 shares in a firm, and that firm decides to issue dividends at the rate of $ 0.50 for every single share held by a shareholder, such a shareholder therefore stands to benefit from a 50 dollar cheque.

Property dividends

Sometimes, a firm may decide to give its shareholders’ company property, in place of cash, to represent the issuance of dividends. However, it is worthy of note that there are a number of tax ramifications that usually accompany this exercise. To start with, the amount of property that a firm chooses to distribute to its shareholders symbolizes the property’s fair market value (Rodriguez 1992) , usually lowered by any form of a liability that shareholder may assume, or even any other liability that such a property in question could be subjected to.

The amount of property that a firm distributes is usually considered to be a dividend at a time when the firm has adequate profits and earnings (E&P), for purposes of ensuring that their distribution is even (Rodriguez 1992). Should the E&P be less than that value attached to the property that a firm wishes to distribute, it is important to note that such an excess is often not considered as being a dividend. Rather, such an excess symbolizes a return on capital (nontaxable) first to use against the basis of a shareholder in question, up to a time when its value has been reduced back to zero. At this point, it is a symbol of a taxable gain, on the part of a shareholder.

Then again, a shareholder’s basis with regard to the distributed property has an equivalent value with the property’s fair market value, during the time when it is being distributed (Zhao 1999). For the sake of a basis, this value so attached to the property is not usually lowered by any debt that such a property could be associated with. A shareholder’s basis acts as a yardstick to either the future loss or gain of an individual investor, at a time when such a property is to be sold.

Alternatively, an investor’s basis could also be an index of the property’s depreciation deductions, in case such a property depreciates in value before the shareholder has disposed it of. It is important to put in mind here that the basis of an individual shareholder may not necessarily be similar to that of the firm (Modigliani 1982). For this reason, there is a need to carefully make a choice about the property that is to be distributed.

The act of distributing property in the form of a dividend to stockholders in a firm has been shown to affect the E&P of a firm (Rodriguez 1992). In this case, any gain that a firm may recognize, following the distributions of property, shall affect the E&P of a corporation, thereby increasing it. On the other hand, such a gain could also be reduced by the larger basis of a firm, with respect to the value of the distributed property. In case such a property is saddled with a debt, what this means is that such a debt shall act to lower the E&P.

Stock dividends

Stock dividends are those dividends that a firm pays out to its stockholders, usually as extra stock shares (Shiller 1984). Stock dividends are normally issued to reflect the number of shares that shareholder has in a company. For instance, in case an investor has a total of 100 shares in a given firm, and this firm decides to give stock dividends at the rate of 5 percent, based on the number of individual shares, then this particular shareholders stands to benefit from 5 additional shares.

In case this kind of payment entails new shares being issued, then we have a scenario that resembles the activity of a stock split, seeing that the cumulative amount of shares that a shareholder has tends to increase, and at the same time, the price of individual shares reduces, but this does not alter market capitalization, nor does it change the cumulative value of the shares that a given stockholder has at their disposal.

A case example:

XYZ Corporation has realized profits and earnings to the tune of $ 100,000. The corporation then decides to distribute one of its assets to a shareholder in the corporation, by the name of Jane. This asset that is distributed to Jane is valued at $ 10,000. The basis of XYZ Corporation on the asset to be distributed to Jane is to the tune of $ 6,000. At the same time, this asset is faced with a debt that amounts to $ 1,000. Jane gets taxed a dividend that is equivalent to the value of the asset being distributed to her, less the debt, translating into $ 9,000. In this case, Jane’s basis with respect to the asset stands at $ 10,000, because the value of the assets is not yet reduced by the debt.

The rate of taxation to XYZ Corporation is at $ 4,000, with regard to the gain that the fi5m gets, following the distribution of the asset (that is $ 10, 000 less $ 6,000). At first, the corporation’s E&P rises, thanks to the gain of $ 4,000. Nonetheless, the firm’s E&P is lowered by $ 9,000 (that is, $ 10,000, less the debt of $ 1,000), translating into a total reduction of E&P of $ 9,000.

Divided decision policy

One of the principal corporate finance theories is that of dividend decision policy. Dividend signaling model has been amongst a number of enduring points of discussion, amongst academicians and researchers alike, with a wide range of studies outlining circumstances under which the management of a firm could utilise cash dividends as a way of conveying information regarding a firm’s level of profitability.

According to DeAngelo and colleagues (2000), the exiting juxtaposition regarding the continues robust hypothetical interests between on the one hand, the signal models and on the other hand, inadequate experimental; support, has ensured that dividend signal gains relevancy as a vital; and unsettled issue within the field of corporate fiancé. Miller and Modigliani (1961) suggest that owing to the assumptions of rational behavior, perfect capital markets, as well as zero taxes, what this implies is that a firm’s value is not tied to the rate of payout over dividends that such a firm may adopt.

On the other hand, evidence exists to support the claim that the prices of stocks usually counteract announcements on changes in dividends within an equivalent market. One of the leading characteristics of an equivalent market is information asymmetry, meaning that the managers of such a firm have vast knowledge regarding the prospects of the firm, when compared with the investors themselves. Consequently, managers of such a firm choose to utilize dividends as a channel for transmitting the future prospects of such a firm.

A majority of the studies provide that subsequent earnings have a higher chance of bearing a positive association with changes in dividends, with the assumption that such earnings usually assume a random walk. Such an observation appears to perpetuate and reinforce the beliefs of individual investors, regarding the relative interaction between earnings and dividends. Therefore, the reactions of the price of a stock, along with a firm’s future earnings performance, are usually triggered by dividend policy.

The model of partial adjustment that was proposed by Lintner (1956) however provides an alternative line of research. This author postulated that an increase in dividend acts as an indicator of a permanent is change in terms of a firm’s earnings, as opposed to an index of future growth earnings.

Further, he opines that the dividend policy of a firm tends to act like the managers of a firm have already set in mind a target dividend (usually a standard proportion over a firm’s current earnings). In effect, the managers regulate such a target dividend, from the previous year’s level, to the new target level. The model by Lintner turned into a hypothetical base for a majority of the present-day models on dividend decisions.

In recent times, Fama and French (2001) have indicated that those firms that trade publicly in the United States are increasingly becoming reluctant when it comes to the issue of dividends payment, for the past 20 years. The authors have issued a report that suggests that there has been an increase in the number of those firms that are leaving out cash dividends. In 1978, 33.5 percent of the firms were seen to omit payments of cash dividends. In 1999, this figure had risen to 79.2 percent.

A rational explanation for this development could be that firms deem it valuable to do without dividend signal. The fundamental theory as regards dividend signaling has been greatly challenged, an indication that there is a need to carry out a further assessment of this area.

Dividends vs. Value: the theory

Perhaps a question that we ought to ponder at this point is if by paying its shareholders more dividends, a company stands to gain an investment portfolio that is more attractive. Surprisingly, the answers to this question that are available in literature suggest a wide varying disagreement, within the context of corporate financial theory.

The ‘Miller-Modigliani theorem’ stands out amongst the propositions regarding corporate fiancé that have received a wide circulation, to this day. According to this theorem, dividends are neutral, implying that they bear no effect on returns (Shiller 1984). One may then tend to wonder how this could possibly be the case.

In a case whereby a certain firm pays extra in terms of dividends on an annual basis, like for example, 4 percent of the price that it holds in stock, as opposed to say, 2 percent which is the normal rate of payment for dividends, would such a development not result in a rise in the cumulative returns of the firm? As per the Miller-Modigliani theorem, this does not happen.

Based on the Miller-Modigliani theorem, the anticipated price increase with regard to this stock shall observe a drop that is equivalent to the value by which the dividend increases, for example between 8 and 10 percent. The result is that we are left with a gross return of a value of around 12 percent.

Even as there still are many scholars and researchers that subscribe to this particular view, nevertheless we still have other theorists who have sought to disagree with the theorem, pointing out that a company could signal its confidence with respect to future earnings through a rise in its dividends. For that reason, the prices of a stock shall be seen to go up at a time when we have an increase in the value of dividends.

Conversely, the stock process shall also fall, in the event that there is a resultant cut in terms of the dividends that are to be issued to a firm’s shareholders (Loughlin 1982). Still, we also have a number of other theorists who contend that by being issued with dividends, shareholders stand to be exposed to higher taxes, with the result that the value of the stocks held by such shareholders reduces. Accordingly, dividends have the potential to decrease, increase, or better still have no impact on the stock price value.

This assertion is nevertheless supported by any of the three arguments that an individual may wish to pursue, at any given time. Dividends have no impact: the ‘Miller-Modigliani theorem’ argues that the idea behind the notion that dividends have no impact on the stock prices is quite simple. Those firms that pay higher dividends shall often provide a reduced price appreciation, in addition to providing similar cumulative returns to its shareholders (Modigliani 1982).

The reason behind such an argument is that the value that is attached to affirm emanates from the various investments that such a firm may have ventured into. Such would include equipment, plant, as well as real estate. In addition, there is also a need to assess is these investments that a firm makes are capable of yielding low or higher returns.

If we have a firm that is paying extra cash to its shareholders in the form of dividends, and such a firm also is capable of floating new shares to the stock market, realize equity and at the same time also assume similar investments like it would have done if at all it had not issued its shareholders with dividends, the result is that the overall value of such a firm would often be impacted upon by the dividend policy of the company.

In any case, the assets that are owned by such a firm, in addition to its generated earnings, will remain the same, regardless of whether or not the firm in question issues its shareholders with large amounts of dividends, or fails to issue any dividend. For an investor, there is a need for one to become indifferent when it comes to the issue of either receiving capital gains, or dividends, in order that this suggestion may hold.

When an investor gets a high rate of taxation on their dividends, when compared to the rate of taxation on capital gains, it may be expected that such an investor would not be very amused with higher dividends, even as their cumulative returns could still remain the same, for the simple reason that they have any obligations to pay more, thanks to the issue of taxes.

Dividends vs. Tax Argument

Historically, there has been a tendency to treat dividends in a less favorable manner, in comparison with capital gains, at least from perspective of tax authorities. For the larger part of the 20th century, dividends have received a similar treatment to ordinary income, with the result that their rates of taxation have been above that of price appreciation, usually taxed and treated as capital gains (Masulis &Trueman 1988). As a result, the payment of dividends acts as a disadvantage to an investor, with regard to tax.

Hence, the payment of dividends ought to lower the returns to stockholders following a deduction on personal taxes. In addition, stockholders need to respond by way of lowering the prices of the stock held by a firm, and which is responsible for settling these payments, as opposed to those firms that do not issue dividends to their stockholders (Masulis &Trueman 1988). The implication of the scenarios so created is that it would be to the benefit of firms not to payout dividends to their stockholders.

There is also the issue of the double taxation that dividends are subjected to; at both the individual and the corporate level. It is important to note that this issue has not received a direct addressing within the confines of the tax laws in the United States, although it has extensively been dealt with in other countries, like Britain.

In such countries as Britain, individual investors usually benefit from a tax credit, to go towards the corporate taxes due to cash flows, and which the stockholders in a company usually receive in the form of dividends (Ibrahim 2003). However, this is not the case in such other countries as Germany, whereby that portion of the earnings of an investor, usually paid out in the form of dividends, gets to be taxed at a reduced rate, when compared with that portion that a firm decides to re-invest.

Even as we explore the various tax disadvantages that surround the issuing of dividends, a majority of the firms still opt to payout dividends to their stockholders. Additionally, investors in such firms characteristically look at these types of payments positively (Ibrahim 2003).We have a number of practitioners and academicians contending that dividends are in fact good, and as such, they have the potential to increase the value of a firm.

To support this assertion, proponents have provided a number of reasons. To start with, these proponents argue that investors favor dividends. Such investors could be paying little in the form of taxes and as a result, they are not bothered by the issue of tax disadvantage, and which has been seen to bear a connection with dividends.

Alternatively, these same investors could be in need of, or attach a great value to, the cash flow that the payment of such dividends usually generates (Ibrahim 2003). One wonders then, why firms fail to sell the stock that they hold, as a way of realizing that cash which they are in need of. It is important however to note that the transaction cost, coupled with the challenges that surround the act of breaking up small stock holdings, and the consequent selling of these shares, could very well cause that activity of offloading stocks that are in small amounts quite unfeasible.

Owing to the enormous variety of institutions as well as individual investors that are to be found in the market, one may not be surprised that with time, there is a tendency for stockholders to invest in those firms that have dividend policies that are in line with their preferences (Fama & Jensen 1983a). For the stockholders that are to be found in the high tax brackets, and who are not in need of the cash flow that results from payments of dividends, there is a tendency for such investors to make an investment, in those firms that issue no dividends at all, or if they do, at very low rates.

On the contrary, those stockholders that are to be found in the low tax brackets, and whose require cash in the form of payable dividends, shall often tend to invest in those firms that issue high dividends (Fama & Jensen 1983a). Such a clustering of stockholders within firms that possess dividend policies that are in line with their preferences is a concept that has been referred to as ‘the clientele effect’. In this case, the clientele effect could perhaps offer an explanation as to why some firms both pay out dividends to their stockholders, and at the same time also seeks to increase such dividends, in due course.

Another reason that proponents have offered to suggest that dividends are good is that markets usually look at dividends as forms of signals (Docking & Koch 2005). In this case, financial markets are seen to explore every single action taken by a firm, in order to assess the possible implications in the days ahead. At a time when firms issue alterations in dividend policy, they are in effect putting across valuable information to the markets, intentionally or otherwise.

Through a rise in the value of dividends, firms are in fact committing themselves to settle such dividends, eventually. As a result of the willingness by firms to assume such kind of a commitment, the impression this creates to investors is that firms are convinced that they are capable of generating the desirable cash flows, ultimately. This kind of a positive signal should hence cause investors to raise the price of the stocks (Docking & Koch 2005).

A reduction in the value of dividends acts as a negative signal, mainly due to the fact that firms are usually less inclined to resort to a reduction in dividends (Docking & Koch 2005). Accordingly, at a time when a company opts to assume this action, the implication is that the markets view it as a sign that such a company is not substantial, and that it could be riddled with long-term financial woes. For this reason, these kinds of actions result in reductions in terms of the process of stock.

Thirdly, we have proponents who harbor the argument that with some managers, it is not an easy task trusting them with cash. It is important to point out here that not all firms possess competent management and sound investment teams.

Should the investment prospects of a firm turn out to be poor, and at the same time, the managers of such a firm do not appear to be careful custodians of the wealth that investors have in such a firm, in the form of stocks, what this means is that by paying out dividends, this will act to lower the amount of cash that such a firm holds, and a possible wastage, with respect to investments.

Theories of dividend

Signaling Models

The asymmetric information for market imperfections acts as the foundation for three discrete attempts to give an explanation to corporate dividend policy. The alleviation of the asymmetries of information that exists between the owners of a firm and the management through unexpected alterations in terms of dividend policy acts as the foundations stone of the signaling models, with regard to dividends (Fama & Jensen 1983a).

The agency cost modes utilize dividend policy in a bid to better support the corporate managers’ and shareholders’ interests (Easterbrook 1984). On the other hand, the models of free cash flow act as an ad hoc amalgamation of both the agency cost and the signaling paradigms; that dividends payout has the potential to reduce available funds levels for gratuity consumptions by the managers of the firm in question (Easterbrook 1984).

Akerlof’s hypothesis of 1970 involved the market for used cars to symbolize a collective equilibrium, without the use of signaling activity. In this case, this model helped shed light on the costs associated with information asymmetries. In 1974, Spence sought to generalize the model by Akerlof, a paradigm that turned into a prototype for the entire financial signaling theories.

The Spence model offers an explanation to a specific and unique signaling equilibrium that enables individuals looking for a job to signal to their prospective employer those qualities that they are in possession of. Even as the basis for the development of this scenario is the employment market, nevertheless Spence opines that there is the possibility of extending this model to incorporate additional settings, such as promotions, admissions procedures, as well as credit applications. There are also a number of authors that have provided signaling models with respect to corporate dividend policy (for example, Kale and Noe1990; Rodriguez (1992).

Those in support of the signaling model are of the opinion that when a firm’s dividend policy is utilized as a tool for conveying across quality issues, then, this model may be said to enjoy reduced costs, when compared with other models. By using dividends to acts as signals, the implication here is that optional signaling techniques are not perceived as being a perfect substitute (Spence 1974).

Tax-adjusted models

The theory of tax-adjusted theorem deduces that investors not only secure elevated and expected earnings over those shares held by the stock-paying dividends, but they also require these. Tax liability obligation over dividends results in an increase in the payment value of a dividend and by extension, the pre-tax return of a shareholder also increases. The capital asset pricing hypothesis postulates that investors give a reduced price to acquire shares on the basis of the tax liability that surrounds dividend payment, in future.

One of the repercussions of the model of tax adjustment has to do with investors’ divisions into clienteles’ dividend tax. This proposition was for the first time put forth by Miller and Modigliani (1961), in one of their decisive work. Modigliani (1982) discovered through later research that the clientele impact accounts for just a nominal change with respect to portfolio composition, as opposed to the foremost differences that Miller (1977) had predicted.

Masulis and Trueman (1988) represent the payment of cash dividends in the form of differed dividend costs. The model by these authors forecasts that those investors that are faced with contradictory tax liabilities may not experience uniformity, with respect to the dividend/investment policy of the ideal firm that they seek. When tax liability tied to dividends decrease or increase, the payment of dividend also increases. Alternatively, it may decrease. At the same time, there is a resultant decrease or increase in earnings reinvestment.

Investors’ segregation into the clienteles results in a reduction of differences so observed. Farrar and Selwyn (1967) develop a model that presumed that the after-tax income of a dividend is usually reduced by investors. Within a framework of partial equilibrium, investors within a firm are usually faced with two options. First, individual investors have the choice to decide on the total amount of corporate or personal leverage.

Alternatively, they may also make a choice if they wish to receive capital gains or dividends, as a symbol of corporate distributions. This model, as postulated by Farrar and Selwyn (1967) argues that there is no need for a firm to payout to its stockholders any dividends. Instead, the model contends that use should be made of share repurchase, in a bid to distribute the earnings of such a firm.

The model by Farrar and Selwyn (1967) has also received an extension by Brennan (1970), in the form of a general equilibrium framework. The resulting setting ensures that investors are in a position to increase the wealth utility that they expect. Even as this model appears to be quite robust, nevertheless its predictions bear a resemblance with those that have been featured by the model by Farrar and Selwyn model; that there lacks an equilibrium with respect to those firms that are paying dividends, and that such an equilibrium does not measure up to the requirement of a zero return for every unit of dividend that is issued. Separately,

Auerbach (1979a) has endeavored to create an infinite-horizon, discrete-time model that enables the stockholders (other than the marketed value of a firm) to increase their wealth. In the event that a dividends tax/capital gains differential is present, what this implies is that wealth maximization ceases to symbolize the maximization of the market value of a firm. Consequently, Auerbach (1979b) argues that the distribution of dividends happens as a result of the long-term and consistent undervaluation of a firm’s corporate capital.

It is important to note that undervaluation occurs due to a dynamic process that takes into account a manifold of total reinvestment of the entire profits made by a firm and subsequently the returns of a firm that are below an investor’s expectations. Tax-adjusted models have been the subject of criticism, on grounds that they lack compatibility as far as rational behavior is concerned.

As a result of this kind of a criticism, Miller (1986) was promoted to opine about a tax sheltering strategy with respect to income, by those individuals that are in the income brackets that are subjected to the highest rates of taxation. In this case, individuals have the choice of desisting from buying those shares that eventually yield dividends, as a way of avoiding the liability that is usually tied to such payments.

On the other hand, through the applications of a strategy that Miller and Scholes advanced for the first time in 1978, stockholders may buy these dividend-paying stocks, followed by the receiving of distributions. Concurrently, the stockholders may decide to borrow funds, with a view to investing in securities that are non-taxable.

Agency Cost model

For over three centuries now, differences with respect to ownership and management separation have been recognized. The present-day agency cost theory attempts to give an explanation to the capital structure of a corporation, as a consequence of efforts at reducing those costs that are related to the control and ownership separations in an organization.

Research findings indicate that those firms that are characterized by strong managerial- ownership relationships also tend to have stocks of lower value. This is due to better alignment of the goals of manager, along with those of the shareholder (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). This is also the case for those firms that are characterized by a huge backlog of stockholders, but are still in an ideal position to assess the activities of their management (Shleifer and Vishney 1986).

Potential transfer of wealth from the holders of bonds to stockholders via high-return and high-risk projects acceptance by the managers of a firm, information asymmetry, as well as the inability of corporate managers to acknowledge NPV (net present value) projects (Barnea, Haugen, and Senbet, 1981).

The aforementioned reactions are usually influenced by dividend policy in two ways. To start with, Fama and Jensen (1983a, 1983b) advocate that potential bondholder and shareholder conflicts could very well be reduced by giving priority to a claim on covenant governance. There is the possibility of circumventing such kinds of orderings through way of large dividend payments.

According to John and Kalay (1982), debt covenants ought to be viewed as important elements when it comes to the issue of dividend payments, as they help to mitigate the transfer of wealth from the bondholders to the shareholders. Even as it occupies a central position with regard to agency costs precipitation, nevertheless its dividend policy should not be viewed as a significant source of expropriation of bond wealth.

In a majority of the firms in which the payouts of dividends are usually restricted by bondholder covenants, the levels of dividend payout still appear to be far less than the allowable maxims level, due to such constraints so adopted (Kalay, 1982b). Another way through which dividend policy may impact the agency cost is through a lowering of these costs via a rise in the levels of monitoring, by the various capital markets. In this case, the payment of large dividends seeks to lower the available funds for purposes of gratuity consumptions, as well as investment opportunities, with the result that managers are often called upon to source financing means from the capital markets.

When the capital markets are monitored in an efficient manner, what this does is that it results in a lowered ‘less-than-optimal investment activity’, in addition to surplus gratuity consumptions. Consequently, those costs that are linked to control and ownership separations are also reduced (Easterbrook, 1984).

Behavioral Models

There are not many paradigms that have endeavored to completely offer an explanation to the behavior that is exhibited by corporate dividends. Even then, Shiller (1984) has opined that attitudes and societal norms substantially impact investor behavior. Sadly though, financial theorists have opted to ignore this motivation, primarily due to the difficulty associated with the activity of introducing investor behavior when it comes to the conventional models of financial pricing (Arbel, Carvell and Postnieks 1988).

Shiller (1989) opines that the incorporations of these influences in an effort at modeling may very well assist in the creations of a theory that would seek to offer an explanation to the activity to corporate endurance over dividend policy. The ordinary investors, usually have to contend with uncertainty, as opposed to risk, such as the absence of objective evidence, as well as concise judgment.

In addition, trading and judgment errors due to shareholders’ activities may result in social pressures. Such judgmental errors are not lapses that could impact rational investment activity, but are more of mistakes. According to Shiller (1984), the aggregate market activity is significantly impacted by mass investor psychology.

It is also important to put in mind that there is a certain level of inconsistency between on the one hand, the dividend policy and on the other hand, a shareholder’s wealth maximization. Such a phenomenon is better explained through the incorporation into the models of economics, a behavior-socioeconomic paradigm.

Additionally, the payouts of dividends may be received as a corporate evolution’s socioeconomic repercussion (that is, the existing information asymmetries between the shareholders on the one hand, and the managers, on the other hand, an interaction that results in an increase in dividend payout, thereby increasing equity issues attractiveness) (Frankfurter and Lane, 1992).

Michel (1979) has talked of a systematic interaction between dividend policy and industry type, implying that the actions were taken by executives for firms that are competitive in nature, usually influences managers, at a time when they are assessing the levels of dividend payouts. When managers realize that the desire of shareholders is to increase dividends, they then opt to increase or pay these dividends, in a bid to mollify the stockholders (Frankfurter and Lane, 1992).

By paying stockholders dividends, ought to assists in increasing the stability of a corporation, by way of acting as ‘a ritualistic reminder’ of the relationships between ownership and management (Ho and Robinson, 1992). Frankfurter and Lane (1992) opine that dividend policy is to some extent, a kind of a tradition and to some other extent, a tool that is used to dispel the fears of an investor.

Free Cash Flow model

Far-sighted managers that have the best interests of the shareholders at heart should see it as their obligation to ensure that they have invested the stocks of the company in as many profitable opportunities as they possibly can getting their hands on. Thanks to the ownerships and management separation action, through the agency cost, the corporate management of a firm is afforded the temptations to either waste extra funds, or consume these.

The idea that the management of a firm could excessively use the funds of a firm beyond what is recouped from profitable investment opportunities was explored for the first time in 1932 by Bearle and Means. This assertion was later on updated in 1986 by Jensens, through his free cash flow model, which sought to integrate the asymmetries of market information with the agency model.

That amount of funds that remain following the financing of the entire positive NPV (net present value) projects leads to conflicts of interest amongst the shareholders and the managers alike. The payment of debt interest, along with dividend payout, serves to lower the amount of available free cash flow to the managers of a firm, for purposes of making investments into marginal NPV projects, in addition to the gratuity consumptions by the management. Such an integration of signaling theory and the agency model ought to act as a guideline to dividend policy, as opposed to top theory per se.

Nevertheless, the theory of free cash flow is touted as a better form of such an explanation, mainly because it seeks to rationalize the takeover frenzy that was a characteristic of many corporations in the 1980s (Myers, 1987 and 1990), more than it does by way of giving an observable and comprehensive dividend policy.

Effects of dividend policy on the volatility of stock price

In as much as a lot of years in empirical and theoretical research have been dedicated to studying the issue of dividend policy, nevertheless it still remains controversial. Allen and Rachim (1996) have sought to explore the kind of interaction between the risk of a stock price and dividend policy. Gordon and colleagues (1980) observed that when a firm pays its stockholders large amount of dividends what this does is helps to lower the risk that is associated with the firm’s stock price, in effect impacting on the price of a stock.

Moreover, such a development also acts as an index for a firm’s future earnings (Baskin 1989). There are several hypothetical mechanisms that have thus far been suggested, and which have been seen to result in an invariable variation of the ratios of dividend payout and yield, with respect to the volatility of common stock. These theoretical mechanisms include the effect of rate of return, duration effect, information effect, as well as arbitrage pricing effect.

By a duration effect, the implication here is that those dividends that are capable of a high yield, give a cash flow that is near term. At a time when we have a stable dividend policy, what this means therefore is that the stocks with a high dividend shall also enjoy a lesser duration. The Gordon Growth Model may be employed for proposes of forecasting whether high-dividend shall experience a lesser sensitivity as a result of fluctuations in the rates of discount, in effect resulting in a reductions in the volatility of prices.

The argument of the agency cost, according to Jensen and Meckling (1976) argues that the payment of dividends results in costs reduction, and a resultant increase in the amount of cash flowing into a firm. The implication here is that when dividends are paid, this acts to motivate the management of an organization, so that they are now in a position to dispel cash, as opposed to investing the same at a rate that is far less below capital; cost, or even squandering of such cash on inefficiencies of the firm (Rozeff 1982; and Easterbrook 1984).

A number of authors have underscored the amount of significance that is tied to an information content, with respect to dividend (for example, Asquith and Mullin 1983; Born, Moser and officer 1983). According to Miller and Rock (1985), the announcement of dividends acts to shed light on the lacking pieces of information as regards a corporation. In addition, dividend announcement gives room to the stock market to approximate the current earnings of a firm. There is the possibility that investors could gain more confidence that those earnings that are reported by a firm are a pointer to the economic profit, at a time whence such announcements are made in the company of sufficient dividends.

As long as investors have a certain level of certainty with regard to their individual opinions, then they could respond to sources of information that they deemed as being questionable in a less reactive manner. Furthermore, there is a chance that their expectations with regard to value could benefit from a cushioning effect against irrational influence.

Gordon and others (1980) have explored the effect of rate of return. This effect provides that a corporation that is characterized by low dividend yield and low payout has a tendency of receiving a higher valuation with regard to investment opportunities in the future (Donaldson, 1961). As a result, the stock price of such a firm is more susceptible to a higher level of sensitivity, due to alterations in rate of return estimates, for an extended period of time. In this regard, although those firms that are in the process of expanding could be characterized by reduced dividend yield and payout ratio, nevertheless such firms tend to show signs of price stability. The reasoning behind this could be that dividend payout ratio and yields act as a yardstick for a firm’s forecasted growth opportunities.

If profit projections as a result of growth opportunities of a firm appear to be somewhat less reliable when compared with projections on return on the assets of a firm, then those firms that exhibit low dividend payout and yield have a chance of showing greater price volatility. On the other hand, the effect on rate of return indicates that the payout ratio and dividend yield are both significant.

Dividend policy could act as an index for a firm’s investment and growth opportunities. The effects of rate of return, along with the duration effect, have been seen to presume differentials when it comes to the issue of timing for a firm’s underlying cash flow. Should the interactions between dividend policy and risks still persist, even after growth of a firm has been accounted for, what this would appear to suggest is that there is some evidence for the existence of either the information or the arbitrage effect.

Experimental research studies have attempted to explore the variation that exists between on the one hand, CAPM beta coefficient and on the other hand, dividend payout ratios. Beaver and colleagues (1970) projected CAPM betas for a total of 307 firms in the United States. Results show that this study yielded a profound link between the dividend yield and beta. Rozeff (1982) discovered a high rate of association between betas and value line CAPM, and the payout for dividends for a total of 1000 firms in the United States.

Fama and French (1992) have concentrated on dividends as well as additional variables of the cash flow, like investment, accounting earnings, and industrial production, in a bid to offer a better explanation to stock returns. Baskin (1989) has opted to assume an approach that is slightly different from the other scholars, and explores the influence that the dividend policy has over the volatility of stock price, and not returns.

The challenges in any form of experimental work that seeks to assess the association between the volatility of the price of a stock or returns on the one hand and dividend policy on the other hand, lies in the creation of sufficient control that would take care of the additional factors. For instance, the accounting system yields information regarding a number of interactions that are assumed by a majority of the individuals as a potential indicator for risk.

However, Baskin (1989) proposes the application of a number of control variables, as a way of testing the importance of the interaction between on the one hand, price volatility and on the other hand, dividend yield. These control variables include firm size, operating earnings, debt financing level, growth level, and payout ratio. These variable not only impact the stock returns, but they also tend to affect dividend yield.

Elements affecting stock price

Over time, we have had a huge number of experimental studies that have been carried out in order to assess stock process determinants. Such elemental factors, as they impact the process of a stock, have been explored from divergent perspectives. A number of researchers have explored the kind of relationships that exists between the stock prices, and chosen external or internal elements.

The outcome suggests a multitude of findings that are based on the scope of a research study in question. A number of these elements might very well be common to nearly all the stock markets. Nevertheless, it becomes quite hard to take a broad view of the results, owing to the diverse conditions which envelop an individual environment to a stock market. For example, an individual market is characterized by unique rules and regulations, the investor types, country of location, in addition to additional elements that ensure that it remains quite unique, in the face of other stock markets.

It has been the conclusions of a number of studies that the fundamentals (for example, valuation multiple, and earning) are the most important elements that impact the prices of stocks. Still, we have other research studies that indicate that economic conditions, the behavior of an investor, inflation, liquidity and market behavior, appears to be the elements of a stock price that are most influential.

Nevertheless, this research study wishes to explore a firm’s fundamental, along with the external factors of a firm, as the elements that impact the most on the stock price of such a firm.

A Firm’s internal factors

On the whole, such fundamentals of a firm like dividend per share, earnings per share, in addition to a host of other elements that acts as a sign of the performance of a company, are often regarded as internal factors to a firm. Hartono (2004) sought to explore the impact of a series of both negative and positive earning and dividend information on the prices of a stock. The data that this study utilized was obtained from the United States for the period between 1979 and 1993 using CRSP (Center for Research in Security Prices) tapes.

The ensuing results from this study indicate that the positive information on the recent earnings of a firm bears a significant connection to the prices of stocks, if it is preceded by dividend information that is negative, and that the recent information on negative earnings has an important link to the prices of stocks if it is preceded by positive dividend information. Conversely, recent dividend information that is positive bears a strong correlation with the prices of stock at a time when it is preceded by negative earning information.

At the same time, recent dividend information that is negative enjoys no substantial correlation with the prices of a stock, if it is preceded by positive earnings. This study indicates a reaction to the process of a stock that is short-term, relative to the information on dividend and earnings, but fails to shed light on a dynamic relationship that is long-term.

Lee (2006) has made use of two forms of cumulative index data: the annual S&P(Standards and Poor’s) 400, and annual DJIA(Dow Jones industrial average) index data. This data was for a sample period that spanned from 1920 to 1999, in the case of the DJIA, and from 1946 to 1999, in the case of the S&P.

According to the revelations of this research study, it emerged that investors usually have a tendency to overreact when it comes to non-fundamental information. However, with respect to fundamental information, Lee (2006) found out that investors usually have a tendency to under-react, without a profound reversal connection with such fundamental information, ultimately. In this case, fundamental information would include the book value, dividend, and earnings.

Further, the study also discovered that the models on residual income offer a far better valuation, when compared with the model on dividend discount. In a study in which they attempted to explore the reaction of investors, following a decrease or an increase in dividend, Docking and Koch (2005) illustrates that the announcement of a change in dividend draws out a far greater change with respect to the prices of stocks, at a time when the nature of this kind of new (whether bad or good) directive fails to conform with the existing market directions when the conditions in the stock market are quite volatile.

To start with, an announcement by a firm that they intend to raise dividends to be issue to their stockholders has a tendency to bring forth a large rise in the prices of a stock, at a time when the returns within the stock market have either been down or normal, as well as more volatile. Nonetheless, such a tendency is deficient in terms of statistical importance. Subsequently, an announcement that a firm intends to lower the rate o payment of dividends to its stockholders has a tendency to bring forth exceedingly larger decrease interns of the prices of stocks, when the returns from the stocks market are both more volatile, and they have been up.

Separately, Al-Qenae and colleagues (2002) made a significant input through an assessment of the impact so earnings, along with other variables of macroeconomics, as they affect the prices of stocks at KSE (Kuwait Stock Exchange) for the period between 1981 and 1997. The variables of macroeconomics that these authors sought to explore include GNP (gross national product), inflation, and interest rate.

The study that was carried out by these authors revealed a high and profound sense of ERC (estimated earning response coefficient), in relation to the stock market’s leading period returns. Furthermore, interest rate and inflations were both found to possess negative as well as statistically important coefficients, in virtually all the various cases that affected the prices of stocks.

On the other hand, GNP was found to have a positive effect, albeit with another limitation; its significance is only realized in the presence of certain return measure intervals, and usually, such measure intervals tend to be high. In light of this, the study by Al-Qenae and colleagues (2002) appears to augment the notion that those stockholders that have invested at the KSE are capable of predicting earnings, and this attempt to indicate that the features that are exhibited by the KSE market are those of semi-strong efficiency. What this means is that a scenario is created, one that allows the prices of stocks to integrate all the information that is available publicly.

A firm’s external factors

As has previously been indicated, consumer prices, interest rates, gross domestic product, as well as oil prices, rank amongst the most fundamental external elements of a stock price. In 2001, Ralph and Eriki undertook an empirical study that endeavored to explore the link between the rates of inflation on the one hand, and the process of stocks, on the other hand.

This study was carried out at the stock market in Nigerian, and it gave ample evidence to support the claim that indeed, inflation exercises a profound negative influence as far as the stock prices behavior is concerned. In addition, this study has also indicated that the prices of stocks tend to be influenced in a strong way by economic activity levels, usually assessed using such yardsticks as the interest rate, GDP, financial deregulation, and money stock.

In contrast, the study by Ralph and Eriki indicated that the volatility that usually characterizes the prices of oil does not have a profound impact on the prices at the process of stocks. In 1999, Zhao examined the interaction among output (industrial production), inflation, and the price of stocks within the economy of China.

This study by Zhao sought to make use of monthly values for the period between 1993 (January) to 1998 (March). Results of this research study reveal a negative and profound link between on the one hand, the prices of a stock and on the other hand, inflation. Further, the results of this research study also show that the prices of a stock are significantly and negatively affected by output growth.

Dimitrios Tsoukalas (2003) has sought to explore the connection between macroeconomic factors and the prices of a stock, by examining the Cypriot equity market, as an emerging economy. The author, in this particular study, has sought to utilize VAR (vector autoregressive model). Industrial production, exchange rate, consumer prices, and monetary supply are the macroeconomic factors that were assessed by Dimitrios Tsoukalas (2003), in a study that covered a period spanning 23 years (from 1975 to 1998).

According to the results of this research study, there emerged a strong connection between the macroeconomic factors under scrutiny, and the prices of the stock. Dimitrios Tsoukalas (2003) asserts that a strong association between exchange rate and the prices of a stock ought not to be a source of surprise, given that the economy in Cyprus mainly relies on such services as off-shore banking, as well as tourism.

Dimitrios further opines that the association between the prices of a stock and money supply, industrial production, as well as consumer prices, is a depiction of those policies of macroeconomics that the fiscal and monetary authorities in Cyprus have implemented.

Separately, Ibrahim (2003) has utilized both VAR modeling as well as cointegration, in a bid to assess the dynamic relationships and long-term association between the equity market in Malaysia, a variety of economic variables, and also a number of major equity markets that are to be found in Japan and the United States. This study utilized aggregate price level, real output, exchange rate, and money supply as the macroeconomic variable. Consequently, two fundamental findings emerged from this research.

First, there is a positive interaction between the Malaysia stock index on the one hand, and industrial production and consumer price index, on the other hand. Secondly, this study revealed a negative association between exchange rates movement and the Malaysia stock index.

Another pair of scholars from Japan, Mukherjee and Naka (1995) have also endeavored to explore the link between a total of six macroeconomic variables, as they impact the stock price at the Tokyo Stock Exchange, though the application of a VECM (vector error correction model ). The research study by Mukherjee and Naka (1995) was made up of a total of 240 monthly observations.

These observations exhausted the six different variables of the study for a period that spanned from 1971 (January) to 1990 (December). According to the research findings of this study, the interactions between on the one hand, the stock prices at the Tokyo Stock Exchange and money supply, exchange rate, and industrial production, was a positive. On the other hand, the kind of interaction between the stock prices at the Tokyo Stock Exchange and interest rate and inflation, was somewhat mixed.

Chaudhuri and Smiles (2004) have attempted to put to test the ultimate interaction that exists between the prices of stocks, and the ensuing real changes with respect to real macroeconomic activities, with a special focus on the stock market in Australia, for the period between 1960 and 1998. Real private consumption, real oil price, real GDP and real money are some of the real macroeconomic elements that were being investigated by this study.

According to the research findings of this study, long-term interactions between real economic activity and the prices of a stock emerged. In addition, this study also revealed that such foreign stock markets as New Zealand and American markets impacted the movement of stock return at the Australian stock exchange, in a profound way.

As an attempt to experiment with the informational efficiency that characterizes the stock market in Malaysia, Ibrahim (1999) has sought to examine the dynamic relationship between a total of 7 variables of macroeconomics, and the prices of a stock, for the period between 1977 and 1996. Ibrahim (1999) opted to apply the Granger causality assessment and cointegration.

The variable of the macroeconomics that this author opted to employ includes consumer prices, credit aggregates, industrial production, M1, M2, exchange rates, as well as foreign reserves. On the basis of the results that emerged out of this research study, there is strong evidence that points towards the existence of information efficiency with the stock market in Malaysia. What this means is that a cointegration exists between the macroeconomic variables that this author utilized, and the stock prices.

This research study is also an indication that the movements of the prices of a stock act as a predictor of a discrepancy in money supply, industrial production, as well as exchange rate, even as these react to alterations from long-run path courtesy of credit aggregates, consumer prices, as well as foreign reserves.

The dynamic interactions that exist between the stock markets in Singapore and macroeconomic variables have been explored by Maysami and Koh (2000), by utilizing such tools as the model of vector error correction. Short term and long-term interest rates, domestic exports, exchange rates, industrial production and inflation are the macroeconomic variables that were of interest to this particular research study.

Furthermore, the data that was being utilized by this research study that encompassed the period between 1988 and 1995, was also subjected to a seasonal; adjustment. This research study indicates that money supply growth, alterations in long and short-term interest rates, inflation, as well as alterations in the rates of exchange, collectively contributes to a co-integration association with the alterations in the market levels at the stock market in Singapore.

In addition, this study also sought to assess the link between the stock markets in Japan and the United States, in addition to the stock market in Singapore. According to the research findings of this study, all of the three stock markets so mentioned, were characterized by a high rate of co-integration.

The interactions existing between the future prices of oil by NYMEX and the stock markets among GOC (Gulf Cooperation Council) countries have also been examined by Hammoudeh and Aleisa (2004). This assessment was concerned with data that covered the periods starting from 1994 to 2001.

Hammoudeh and Aleisa (2004) contend that the export of oil to a great extent, determines not just the earnings that a country stands to gain, in terms of foreign exchange, but also contributes significantly to the expenditures and the budget revenues of the government of such an economy.

For this reason, we have fundamentals determinants of the cumulative demand that impact their domestic price level and corporate output, and which in the long term, affects the prices of a stock and the corporate earnings.

Results from this research study reveal that the index of the stoic market in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) symbolizes the nation that is second in rank (together with Bahrain, but after the market in Saudi Arabia). Going by the review of the literature that has already been explored in this research study, one may then arrive at a conclusion that for the most part, there exists a robust relation between the earnings and the prices of a stock, even as a strong long-term dividend-stock price lack.

Reports also indicate a negative association between interest rates (in the long-term) and prices, while there is evidence of positive associations existing with interest rates in the short term. Industrial production, GDP, and GNP (gross national product) as measurers of real economic activity have a higher probability of experiencing a positive interaction with the prices of a stock. Similarly, money supply seems to experience a positive association with respect to the prices of a stock.

The prices of a stock seem to move in the opposite direction to that of the rate of inflation, courtesy of a negative interaction. On the other hand, the association between the prices of oil on the one hand, and the prices of a stock on the other hand, bears little significance. In summary, the prices of a stock are impacted upon by financial as well as economic elements, and more so by the macroeconomic variable.

Effects of the dividends on the prices of stock

The main objective of any corporate entity is to ensure that the investments made by shareholders in a given firm increases in value. For this reason, managers seek to pursue this goal by way of ensuring that they arrive at sound financing and investment decisions. With regard to investment decisions, these are mainly concerned with the selection of those projects that have a net present value that is positive.

On the other hand, financing decisions are more concerned with choosing a capital structure with the intention of reducing a firm’s capital cost (Chaudhuri & Smiles 2004). Other than financing and investment decisions, there is a need for managers to frequently make a choice regarding whether or not shareholders’ earning should be paid out, effectively minimizing the agency problem (Chaudhuri & Smiles 2004).

Nevertheless, a question that we ought to ponder is whether or not the payment of shareholders’ earnings in the form of dividends would in effect result in value creation, on the part of the shareholder. It is important to note here that the payment of dividends ensures that there is a flow of cash to a shareholder on the one hand, and a reduction on investment resources, on the part of a firm, and this may very well impact the share of the sticks of such a firm.

Towards this end, we have had numerous empirical and theoretical researches that have over the past few decades been carried out, to explore the effect that the payout of dividends has on the price of a stock. Hypothetically, cash dividend implies that shareholders receive rewards from the firm, in the form of cash, given that these shareholders are the one who owns the company, anyway. Consequently, the issuance of dividends shall more than be compensated for by a reduction in the value of the stock of such a company (Porterfield 1959 and 1965).

In the absence of taxes and other financial restrictions, what this means is that the payments of dividends to shareholders would ideally have no effect on the value of the shareholders (Miller and Modigliani, 1961. This however, could only happen in an ideal world. In the real world however, the institution of changes with regard to dividend policy is usually preceded by an alteration in the value of stocks within the market.

Graham-dodd (1951) is credited with postulating the economic argument regarding the preference by investors for income in the form of dividends. Consequently, Walter (1956), followed by Gordon (first in 1959, and later in 1962), advanced the idea of dividend relevancy, which was later to be officially made into a theory.

The idea on dividend relevancy, as forwarded by Walter and Gordon, hypothesizes that the prevailing price of a stock is a reflection of the current value of the entire dividend payments that are expected to be settled in future. We also have a number of other researchers who endeavored to better comprehend the controversy surrounding the issue of dividends, and how they impact the stocks. Some of the notable scholars who made this attempt includes Brennan (first in 1970, and later on in 1973), as well as Litzenberger and Ramaswamy (1979, then later in 1980).

Separately, these scholars indicated that in the event that the rate of marginal taxes subject to an investor is more than zero, then it is more than likely that such an investor would stand a chance to receive nay dividends. Further, these scholars asserted that the discount rate of an investor (that is the ‘after-tax expected rate of return’) hinges upon the systematic risk, as well as the dividend yield (Chaudhuri & Smiles 2004).

The result of this is that we have tempted to harbor the notion that at the very least, dividend could somewhat impact the price of a share, an effect that is tax-induced. The average investors, depending on the tax rates to which they are subjected, would usually desire to experience reduced cash dividends, as long as there are being taxed.

In addition, there is evidence to support the claim that the idea of dividend policy irrelevancy stands, even when we stop presuming the idea of an ideal economy. However, Black and Scholes (1974) postulated that all investors are not subject to a uniform tax effect, owing to the fact that various investors are exposed to varying tax rates based on income and wealth levels.

On the other hand, Chaudhuri and Smiles (2004) hypothesize that there exists an in reverse relationship between on the one hand, optimal dividend and on the other hand, the tax rates that are subjected to personal income. For this reason, there is a tendency for the prices of stocks to decline, at a time when the management of a firm announces that the dividends to be issued to their shareholders have increased.

Nonetheless, experiential studies indicated mixed evidence, through the utilization of data that was sourced from the stock markets in Japan, the United States, and Singapore. Several studies revealed that there exists a considerable positive relationship between on the one hand, the price of a stock and on the other hand, the payment of dividends [Gordon (1959), Ogden (1994), Stevens and Jose (1989), Kato and Loewenstein (1995), Ariff and Finn (1986), and Lee (1995)].

Still, we also have a number of other researchers who discovered negative relationships (for example, [Loughlin (1989) and Easton and Sinclair (1989)]. We may anticipate a negative relationship to exist between the announcement of the issuance of dividends and the ensuing returns on the stocks owing to the tax effect.

Nonetheless, researchers were inclined to connect the positive association between the announcements of dividends and stock prices based on the effect that the available information had on such dividends. According to the dividend information theory, cash dividend is the bearer of information on a firm’s future cash flows, and which are to act as a sign of the price of the stocks in the market, following the announcement that dividends are to be issued, and more so at a time when there is an increase in the value of dividends issued [Bhattacharya (1979) Bar-Yosef and Huffman (1986) and Yoon and Starks (1995)].

The hypothetical literature as regards the effects of the dividend has received extensive attention from researchers and scholars alike. It is generally accepted amongst researchers that on their own, dividends bear no effect on the value of stock owned by a shareholder, from the point of view of an ideal economy. On the other hand, when we turn on to the real world, the announcement of dividends, this is a very significant development to nay shareholder, owing to not just its information content, but also the effect this has on tax.

Cases of dividend-stocks interaction from different markets.

A case study on the impact of prices of oil on stock markets: an assessment of GCC countries

The above-mentioned study was carried out by Mohamed el Hedi Arouri and Chirstophe Rault in a 2009 publication titled, ” On the influence of oil prices on stock markets: Evidence from panel analysis in GCC countries”. The aim of this study was to assess the prevailing long-0term interactions between stock markets in the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) nations on the one hand, and the prices of oil, on the other hand.

From the outset, it is important to note that there are a number of patterns that are common to all the GCC countries. Collectively, these countries account for 20 percent of the oil that is produced globally. In addition, these countries also have a 36 percent controlling stake in the oil exports, on a global scale.

Furthermore, they also account for 47 percent of the global oil reserves that have thus far been proven. Table 1 below is an indication of the level of liquidity of the stock market for the various GCC economies.

Table 1: GCC countries’ stock market (2007).

(Sources: Arab Monetary Fund and Emerging Markets Database, Numbers in 2006).

The authors revealed that fluctuation in oil prices has the potential to directly affect GCC markets on the basis of the influence that they have over import prices. Furthermore oil price increases usually act as a measure of inflationary pressure on the economies of the GCC countries.

Such inflationary pressures, the authors reckon, have the potential to determine the kinds of investments to be made in future, as well as affecting the interest rates. Therefore, amongst the GCC countries, fluctuations in oil process shall usually impact corporate earnings and output. In addition, such a fluctuation shall also affect the sharing process, not to mention domestic process.

Nevertheless, unlike in the case of those countries that are net importers of oil, in which a negative association between stock markets and oil process is expected, GCC countries may be susceptible to additional phenomena: the mechanisms of oil price transmissions onto the returns of a stock market may at bets, be said to be ambiguous.

Furthermore, the overall effect of the prices of oil, and the shock this subjects to the returns of the stock market, shall de be determined by the number of negative or positive effects that act to counterbalance one another. Given that the GCC countries are major players in the exporting and production of oil, it may therefore be expected that the stock markets of these nations are prone to shocks in the prices of oil.

This study by Arouri and Rault (2009) was founded on two distinct (weekly and monthly) datasets that encompassed a period of time spanning two-time frames. First, there was one dataset for the period starting June 7 2005, up to October 21, 2008. The other dataset was from 1996 (January) to 2007 (December).

The results of this research study indicate the existence of evidence regarding the cointegration of the stock markets and oil process, within the GCC countries. These are findings that ought to draw interest from regulators, researchers, and also the market participants. Particularly, GCC nations as part of the policymakers for OPEC, requires watching keenly the impact that the fluctuation of oil prices has on the individual countries’ economies in general, and the stock market in particular.

With regard to investors, the profound interaction between the stock markets and oil prices is an indication of a certain level; of predictability, as far as the stock markets from the GCC countries are concerned.

Case 2: ‘Dividend changes and future earnings performance: evidence from UK market’

The above is a title of a study that was carried out by Gaoliang Tian Hanyue Zhang in 2006 to explore the effect of changes in dividends on the future earning performances of firm, with a special focus on the stock market in the United Kingdom. The paper that was authored by these two authors sought to examine the connection between dividends changes on the one hand, and a firm’s earnings performance in the future on the other hand, on the basis of projections.

First, the study presumed that there is a positive relationship between a firm’s future earnings and dividend changes. That is to say, dividend decreases (increases) shall usually precede earnings decreases (increases). The vice versa is also true. Secondly, this study hypothesised that a positive relationship also exists between on the one hand, dividend changes and on the other hand, the future profitability levels.

The authors sought to undertake a sample that was made up of a total of 406 firms, and which had announced the issuance of dividends to their stockholders between the month of January 1989 and December 2000. However, there are a number of criteria that had to be met by these firms, before they could be taken as samples.

To start with, each of the firms so chooses should have been on the London Stock Exchange list, for the period already described. Secondly, non-British firms were also not included in this assessment. The firms should also payout dividends to their stockholders at the very least, once during the previous as well as the current financial year, often termed as ‘ordinary dividend payment’.

The criteria for selections that were adopted by this study augment the sample’s homogeneity that is made up of a total of 3922 observations, according to table 2 below.

Table 2: ‘A Frequency of Firm-year Observations with at Least One dividend Event by Fiscal Year’

In addition, the samples had a total of 448 decreases, 2588 increases on dividends, and 886 non-changes. The study also indicates that the magnitude that characterizes dividend decreasing firms appears to be somewhat less when compared with that of those firms whose dividend is decreasing. The table has also provided frequency numbers of changes in dividend. Selected firms have been fairly scattered throughout the sample period.

A fascinating phenomenon that is worthy of exploration is that there is a gradual growth of those firms that are characterized by non-change dividends. Initially, this number was 21 in 1989, but had drastically increased to 101, by the year 2000. Nevertheless, this increase in the number of non-change dividend firms does not surpass the scale of increases in dividend.

Case 3: Stock Market in the US

The third case study for this research paper focuses on an article by Jeremy Siegel titled, ‘Stock Market’ that featured on ‘The concise encyclopedia of economic’. The author, buy focusing on the stock market in the united states, argues that the price of a stock, as a financial asset, is equivalent to “the present value of the sum of the expected dividends or other cash payments to the shareholders, where future payments are discounted by the interest rate and risks involved’ (Siegel ).

In this case, this author observes that a majority of the payment that the stockholders in a firm usually receive emanates from dividends. The payout of such dividends comes from the earnings of a firm, in addition to additional distributions following a liquidation or sale of a firm’s assets.

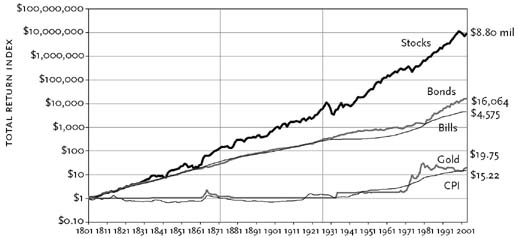

With regard to a rise in return on stocks, Siegel (2008) notes that this could be a result of two causes: capital gains and dividends. With time, the cumulative return on stocks appears to be greater than the positive earnings realized from other forms of assets. An indication of this has been explained by figure1 below, in which the overall returns on stocks, gold, short-and long-term government bonds, as well as commodities (as estimated by CPI-Consumer Price Index).