Abstract

Billions of dollars are spent each year, by firms of varying size and across different industrial verticals, on a software system class popularly labeled Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP). All the evidence points to the software class being solidly in the expansion phase of the product life cycle; that the main proponents continue to open up in less developed economies, seek to increase their penetration of medium and small-scale businesses, contribute to closing the gap for trained manpower, and grapple with competition from two directions all would seem to argue that the business of selling ERP systems has yet to reach the saturation point.

This PhD research defines the robustness of, and short-term prospects for, ERP systems in terms of decision-making needs that have historically underlined the need for resource planning. As well, this thesis embarks on an empirical, data-driven analysis of best practices among end-users and the strategic benefits of deploying such an extensive application. Finally, the research addresses the question of how well ERP has bolstered organizational strengths, identified market opportunities more readily, staved off competitive threats and redressed the shortcomings of firms that compete on a global (or at least international) scale.

Introduction

In many ways, ERP is the very significant nexus between enterprise reliance on IT, on one hand, and strategic management of the enterprise to arrest decline, for survival, to attain sustainable growth and realize growth goals, frequently by reaching out to overseas markets. Clearly, businesses benefitted from IT investments in epochal hardware improvements, that saw the evolution from vacuum tubes to integrated circuits to PC’s in the span of the last five decades.

The ability to manage the strategic direction of the firm grew as IT expanded from merely improving basic transaction processing to streamlining business processes and making available new information to help with management decisions.

With each advance touted by IT into management information systems (MIS) in the Fifties; decision support systems (DSS) in the next decade; computer-based information systems (CBIS) of the Seventies; executive information systems (EIS) during the 1980s and ERP from the 1990s onward, management grew hopeful about getting more timely information, creating sustainable competitive advantage and enhancing shareholder value. Attainment of these strategic guideposts, it became clear in hindsight, proceeded through the six stages postulated by Shank and San Miguel (2002):

- Updating basic transaction processing systems to hurdle legacy problems and achieve transnational capability.

- Attaining interconnectivity, both within each transaction process (vendor, customer, employee, and accounting processes) and among all four.

- Linking transaction processing across the supply chain.

- Building an integrated data warehouse (DW) for all the information generated by the above IT and automation efforts.

- Creating business intelligence: expanding beyond simply transaction data and presenting decision-makers with ease-of-use, “drill-down” analyses and synthesis capabilities.

- Ultimately, ensuring that the newfound data warehouse and business intelligence functionality empowers strategic management in point of sustainable competitive advantage, value creation, revenue goals and global markets penetration.

Ultimately, the goal of all strategic management in the business sector is financial in nature: the conservation of assets or maximizing of financial returns. All other goals are subordinate to this. Without liquid assets, a firm cannot long survive, much less invest in the R & D, physical plant, material stockpiles, training, advertising, and alliances needed to grow. Even sales growth is an illusory goal if it does not throw off healthy cash flows soon enough.

For centuries, therefore, management planning and control centered on oversight of financial resources and returns (Emery, Finnerty, and Stowe, J. D., 2007). Well into the 20th century, enterprises readily snapped up the counting machines, mechanical calculators, ledger printers, and electronic calculators that facilitated the work of their accountants. In the heady 1950s, however, several developments combined to create a new era of broadened resource planning and management.

Among these were urgent pressures to cater to both a booming domestic market and an endless procession of export markets as American producers became multinational marketers. Material resource planning (MRP) emerged as one answer to the need for manufacturing to cater to apparently-insatiable market demand (U.S. Dept. of State, 2008). The work study findings of Taylor (1911), the revealing conclusions of the long study series at GE’s Hawthorne plants, and the work of behaviorists drew attention to the state and well-being of a firm’s human resources.

And as the requirements for informed decision-making about inventories, production, market conditions, dynamic pricing, and employee relations proliferated, IBM and NCR brought their mainframe computers to market. And yet, the batch-processing computing model that persisted till the next generation, minicomputers, accomplished virtually nothing to make management reports more widely accessible.

The advent of desktop microcomputers and networking in the 1980s finally broke the mold of centralized computing and paved the way for SAP of Germany – initially engaged in real-time financial analysis since 1972 (SAP, 2008a) and already a modest success at transferring that core competence to production-side material resource planning – to introduce the novel idea of distributing server-stored information everywhere it could assist planning and decision-making. For the discipline of strategic planning that was then taking its place in the sun, widespread performance feedback and information distribution had intuitive appeal. The era of integrating the enterprise and multi-resource planning had arisen.

The term “enterprise resource planning” (ERP) is supplier-driven since it embraces a rather broad category of commercial software developed by independent software vendors (ISV’s) or providers. Often marketed under varied nomenclature and in software suites embracing a differing array of applications, ERP packages have in common the fact that they integrate vast amounts of information (Algeo and Barkmeyer, 2008) and every activity in the organization (Sane, 2005) that:

- Is amenable to performance measurement;

- Can be managed and planned; and,

- Contributes to business processes and goal attainment.

The third crucial element in any form of ERP comprises its defined purpose of decision support at the day-to-day or “tactical level” of operations and of fostering more systematic operations planning. If, as McGaughey & Gunasekaran (2007) maintain, ERP delivers the right information in up to date fashion to those who need it to make better decisions, then:

- Leaders can make better decisions about all the resources at their disposal;

- Predict, with business intelligence systems and other tools at their disposal, what ought to be done soon with the full panoply of resources; and,

- Thence, reduce costs or help the firm in its overarching goal of creating value.

Given its origins in MRP, it is natural to assume that usability and strategic benefit apply solely to industrial enterprises. However, ERP variants have been successfully developed and marketed to service organizations, such as those in health care or customer relations management (CRM).

Two decades on, enterprise resource planning (ERP) remains a valid model of a business strategy in which the outcomes optimize productivity in financial management, human capital management, order management, manufacturing and operations, and enterprise asset management processes. The total scope of the enterprise software industry extends to: database software, middleware (business intelligence, application integration, portal server, J2EE application server, development tools and identity management), collaboration, development tools, enterprise applications, consulting/systems integration and even operating systems/platforms (Gartner, 2007).

All this because ERP integrators promise that integrating all company data on a set of applications that work seamlessly with each other cuts costs involved in data transformations and ensures that every line and staff unit operates with a common knowledge base that is continuously updated in real time.

So many large industries agree with this basic benefit of ERP that the field of integrators has grown to include many of the best-known names in Information Technology (IT): IBM, Fujitsu, Oracle, Deloitte, Capgemini and Accenture, to name a few (Ibid.). (At Microsoft, the SharePoint “document management and collaboration” suite is integration by another name.) Equally important, ERP adaptation has expanded beyond the United States and Europe.

Purposes for Undertaking This Project

This programme of study continues personal research and professional practice in the field of Information Technology and Information Systems, particularly within the area of end-user systems accessibility.

Within Profit and Non-Profit Organizations, there is evidence of constant innovation and changing approaches to provision of systems integrations; however, the wide ranging and long term issue of user accessibility has clearly become a secondary consideration. My PhD research should underpin improved provision of the importance of the systems for the management to take in concentration when designing the strategies of the Enterprise Resource Planning issues for the organization.

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) implementation is a technological breakthrough that is challenging and changing the operations of businesses and organizations around the world. ERP offer a software-based system that handles an enterprise’s total information system needs in an integrated fashion, ERP focus in on all aspects of operations within a company from Finance, Accounting, Human Resources, Customer Relations, and Inventory to the end result which is the product output or service that the consumer receives. The successful strategic planning of the ERP incorporates the delivery of ERP and implementing the system into the Organizations.

This research and study will focus on ERP system Implementation from a strategic and technical prospective and In the Context of the Global Business Environment. Also it examines the successful or failure factors of ERP projects. It uses a case study methodology to compare a successful ERP implementation with an unsuccessful one. The study proposes that worked with functionality, maintained scope, project team, management support, consultants, internal readiness, training, planning, and will focus on the adequate testing, which will be critical to the successful of ERP project implementation and also dealing with organizational strategies,, development, diversity and budgeting are other important factors that are contributing to a successful implementation.

Aims and Objectives of the Study

The aim of this study is to contribute to the growing body of knowledge in this field by exploring the theoretical foundations underlying the process of the Strategic Planning of the ERP System, In the Context of the Global Business Environment and developing a better understanding of this process based on a holistic view by identifying the critical factors of the project and assessing their effectiveness in the implementation of the project.

I’m not proposing a generic model, just test this model in the context of the global business environment and how it’s affecting it, by looking at the CSF and build an ERP projects based on best practice perspective.

By way of informing the thoughtful decision-maker looking to embark on ERP or to optimize an existing installation, this thesis will:

- Determine what motivates enterprise decision-makers to adopt ERP.

- Define the tools and scope of ERP.

- Isolate the measurable benefits of ERP, notably how enterprise-wide integration strengthens the medium- and long-term strategic position of a firm.

- Critically account for organizational culture and cross-cultural behavior patterns as mediating factors in the success of ERP deployment and its contribution to strategy management.

- Determine the validity of the integrators’ strategy to seek growth by penetrating medium and small businesses (Gold, 2007).

- Scrutinize the opportunities and threats posed by “best of breed” specialist applications as well as the rising tide of remote, software-as-a-service (SaaS) and “pure play” operators (Schwartz, 2007).

- Critically examine lessons of success and failure to be had from a representative set of international case studies.

- Undertake a meta-analysis of the critical success factors and challenges attending implementation of ERP.

- To determine the sustainable advantages ERP endows firms with global operations.

Subsequently, the thesis will arrive at a reasoned judgment on the ROI, sustainable advantage and other strategic benefits of ERP.

Literature Review

Scope of Coverage

This section reviews the relevant literature from several fields of study that is associated with the issues of ERP, the strategic importance of ERP and system architecture and its implementation. These involve 1- ERP definitions, 2- evolution, 3- system structure, 4- system features, and 5- reasons for adopting ERP systems.

In general, this thesis draws on a review of the literature as a first step in understanding the imperatives, strategic significance and present outcomes of ERP as both software and tool for the management of large-scale, globally oriented firms. This is directly related to the question: what is the value of investing in ERP in relation to fostering the competitiveness and sustainable advantage of a firm?

One proceeds to critically examine the information gaps and decision points that encouraged development of appropriate tools and systems. Hence, the review retraces the origins back to the requirements of production planning, proceeds to the next stage of discovering the changes in management theory and the increasing sophistication of information technology (IT) products that both propelled the more insightful understanding, planning and management of the varied resources a firm had at its disposal.

By default, a great deal of the material on product features, components and benefits of ERP systems come from the software and service providers themselves. This cannot be helped since the scope of large-scale integration is ordinarily too vast and technical for anyone but Chief Information Officers (CIO’s), experienced industry analysts and old hands in the trade press to understand. Nonetheless, this review of literature endeavors to counterbalance such bias by obtaining and drawing lessons from applicable case studies.

More thoroughly, the literature review defines the essential elements of ERP, and synthesizes prior discovery and analysis around adoption costs, effects by industry and firm size, where expectations fall short, other drawbacks, and what sustainable competitive advantages have been realized.

Manufacturing Resource Planning (MRP)

The origin of ERP can be traced back to materials requirement planning (MRP). Partly as a result of the scrutiny given to the “just-in-time” supplier relations management practiced by Japanese automakers, the concept of MRP was already understood conceptually in the 1960s and some thought given to automating the process (McGaughey and Gunasekaran, 2007).

Whether done manually or on an automated basis, there are common threads to the understanding of an MRP system. The term was first proposed by Joseph Orlicky in the 1960s and he is therefore regarded as the father of modern MRP systems (Vollmann, et al., 1992). Since then, that system has been improving continuously (Chung and Snyder, 1999; Koh, et al., 2000). Hodson (1992), for instance, defined the system as a time-phased re-order point system for independent demands.

Farmer (1985), on the other hand, views an MRP system as a set of techniques designed to translate a Master Production Schedule (MPS) into time-phased net requirements for the subassemblies, components and raw material planning and procurement. Smolik (1983) and Turbid (1990) refer to an MRP system as a set of calculations that are used to develop a plan for the acquisition of materials needed for production. Thus, an MRP system can be defined as planning and creating a production schedule by integrating and aligning the inbound flow of manufacturing materials with production requirements to create a production schedule.

To sum up, MRP is a software system that is based on planning the entire production and inventory system. Given the vagaries of supply chain management and the complex nature of modern production processes, it is not possible to carry out MRP by hand anymore. If a company purchases fewer materials than what is needed, production commitments may unmet, consumer needs unmet, and market share suffer. On the other hand, a company that overstocks ties up too much working capital in warehousing raw materials and finished goods. Clearly, MRP is extremely important to the wellbeing of a firm.

Chung and Snyder (1999) report that MRP systems were introduced as high level scheduling, priority, and capacity management systems for the use of plant managers and their supervisory staff. Shtub (1999) suggests that the MRP system was developed for the order fulfillment process. He bases this finding on grounds that that the MRP system is a set of techniques that uses simultaneously, a Bill of Material (BOM), inventory data, and Master Production Schedule (MPS).

It combines the marketing information in the MPS with information on current inventory levels and standing manufacturing and purchasing orders, with technological information about the structure of each product and its manufacturing processes. It computes the order quantity and establishes a schedule of planned orders for each item (Figure 1) (Shtub, 1999).

The output of an MRP system includes recommendations on how many units of each product, component, parts or raw material to purchase, to assemble and when to issue the production or purchase order (Shtub, 1999).

Among the three major objectives of MRP, accordingly, primacy is given to:

- Keep the lowest level of inventory in stock and plan deliveries and purchasing. Companies have to control the type of materials that they purchase and they must have an optimal way to plan the products that are to be made and in what quantities the items are made so that the firm meets market and trade demand in timely fashion.

- Reduce cost of goods to the lowest that can be realized.

- While providing markets the type and quality of goods demanded.

Till 1963, however, the computing power just was not available. In existence then were many special-purpose “computers”, sharing no common framework or language. IBM changed all that with the introduction of the System 360 (S/360, for all points of the compass) that ushered in the era of a programmable and very speedy machine capable of replacing platoons of clerks running computations on slide rules and vacuum tube calculators (Kahn, 2004; Johnston, 2005).

To keep pace with more dispersed and complex operations, MRP needed the processing power and greater storage capacity of newer generations of PC’s. At the start, in-house IT staffs endeavored to develop MRP systems on their own and at great expense, rationalizing that there was proprietary interest involved. Eventually, however, third-party systems became robust enough so that MRP became one of the first off-the-shelf business applications (Orlicky, 1975).

From thence to the present, MRP covered taking a master production schedule, maintaining inventory records, and attending to the production bill of materials and planning schedules for material, component, and sub-assembly requirements.

No one gave much thought to forecasting requirements over the medium term. As long as the materials planning system was realistic, lead times known and predictable, inventory records accurate, and the Bill of Materials kept updated, MRP made it possible to calculate material, component, and assembly requirements. The sheer volume of calculations necessary for MRP with multiple orders for even a few items made the use of computers essential. Initially, batch processing systems were used and regenerative MRP systems were the norm, where the plan would be updated periodically, often weekly.

MRP employed a type of backward scheduling wherein lead times were used to work backwards from a due date to an order/start date. While the primary objective of MRP was to compute material requirements, the MRP system proved a useful scheduling tool. Order placement and order delivery were planned by the MRP system. Not only were orders for materials and components generated by a MRP system, but also production orders for manufacturing operations that used those materials and components to make higher-level items like sub assemblies and finished products.

During the 1970s, IBM continued to facilitate the emergence of MRP. First, there was the introduction of the second generation mainframe, the S/370. By the late 1970s, IBM offered the world’s first MRP system, MAPICS. It was an initial step towards providing manufacturing companies with timely information about what was needed to fulfill their customers’ orders. Since then the product, now called MAPICS XA, has been significantly enhanced and redeveloped to become the leading enterprise resource planning system to enable complete supply chain management for manufacturers (Bennett, 1999).

Material Resources Planning II

Due to the aforementioned limitations, over the years new facilities and capabilities were added to the MRP system. These enhancements included capacity planning modules to determine production schedules and reveal capacity shortages and shop floor control modules that utilized limited capacity efficiently (Chung and Snyder, 1999; Shtub, 1999).

Consequently, and since 1975, the MRP system has been extended from a simple Material Requirement Planning tool to become the standard MRPII system (Chung and Snyder, 1999). MRPII systems stand for Manufacturing Resource Planning (Plossl, 1994).

Consistent with the origins of MRP, Chung and Snyder (1999) attest, the second generation MRPII system evolved as an application of even more advanced information and manufacturing technology, plans and resources to raise the efficiency of manufacturing operations. Various sources – among them Gumaer (1996), Shtub (1999), Gupta (2000), and Kumar and Hillegersberg (2000) – are in agreement that MRPII packages are extensions and thus, natural successors of the earlier MRP system.

Other than the heritage of ensuring the efficiency of manufacturing operations, what is the basis for Goddard’s assertion (1990) that MRPII systems are strategic information systems for decision makers? Where Gumaer (1996) affirms that most MRPII systems are focused primarily on material requirements using an infinite capacity-planning model or Markus, et al. (2000) focused on managing a production facility’s orders, production plans, and inventories, Gattorna and Day (1986) take the more integrative view that an MRPII system can be defined as one that integrates the MRP engine with master production scheduling and capacity planning, shop floor control modules to determine production schedules, and discloses capacity shortages. Sarkis and Sundarraj (2000) also take Shop Floor Control (SFC) into consideration in defining the MRPII system as coordinating resource planning with SFC, inventory and other aspects of material management.

One thing is clear: MRPII in place is an information system used to plan and control all the manufacturing activities within the organization.

Transformation in Managing the Total Resources of a Firm

As with many other classes of software and systems, ERP did not come into being all on its own. In fact, ERP evolved from the narrow scope of MRP.

Software and systems packages evolve, adapting to end-user demands, changes in functionality specifications, requirements of the trade and ultimately, consumers. Academicians compare the process of software evolution to those of biological organisms. Software evolution is similar to Darwinism because survival of the fittest has been the rule in this extremely competitive business. Software evolution has evolved and changed as quickly as the human race.

Now that software has reached it peek performance level it is interesting to note that we are starting to see some noteworthy mutations. Stanford University in Palo Alto California seems to have been the breeding ground for the geniuses that have developed computer software to the extent that we use and depend on computers today.

Adaptation and modification is intrinsic to the process of software evolution, both internally and external to the firm. Taking place externally, software evolution is both inevitable and dynamic since it has led to discoveries of many other important uses for computer software, hardware and networks, among them the Internet. Evolution as refinement is also essential, typified by written language and codes being optimized to become efficient running programs and reusable modules. By way of example, the clear superiority of the Apple graphic user interface launched the software evolution that gave birth to Windows on the PC platform. The language of software has evolved to become one of the most sophisticated languages that has ever been spoken in the world. Man has allowed machine to talk to machine.

Meir Lehman (1980) has been carefully studying the process of software evolution since he was a researcher for IBM. According to Lehman, software evolution, i.e. the process by which programs change shape, adapt to the marketplace and inherit characteristics from preexisting programs has become a subject of serious academic study in recent years. Such serious scrutiny owes much to the impact of software systems on the operational efficiency of an organization and its ability to reach strategic goals.

The two most important influences on evolutionary software change has been debugging associated with QA and the effort to put more and more applications on the. As large-scale programs such as Windows and Solaris expand well into the range of 30 to 50 million lines of code, successful project managers have learned to devote as much time to combing the tangles out of legacy code as to adding new code. The most important implication of software evolution has most certainly been the invention of the internet and the World Wide Web. These software programs have evolved from simple chat relay systems to complex communication tools.

Electronic communication and “virtual reality” are the future, today. John Perry Barlow, a founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, says of the evolving realm of online electronic tools that “we are in the middle of the most transforming technological event since the capture of fire.” (Koch, 1996, p. 2). This was a very powerful statement that was made twelve years ago; however it is a noteworthy analogy about the development of the Internet certainly having done more for human history than even the invention of the wheel.

The internet is one of the most important inventions in history because it has allowed man to freely communicate on a variety of channels: VoIP, email, Internet chat and social networking sites. The monumental impact of the Internet on mankind, notably on those who have constant online access, manifests itself in, for instance, the fact that levels of Internet penetration even in Third World countries has exceeded predictions that were made just five years ago.

As MRP systems became popular and more and more companies were using them, practitioners, vendors, and researchers started to realize that the data and information produced by the MRP system in the course of material requirements planning and production scheduling could be augmented with additional data and meet other information needs. One of the earliest add-ons was the Capacity Requirements Planning module, which could be used in developing capacity plans to produce the master production schedule. Manpower planning and support for human resources management thus came to be incorporated into MRP.

Next, distribution and financial management capabilities were added. The enhanced MRP and its many modules provided data useful in the financial planning of manufacturing operations.

Business needs, primarily for operational efficiency and, to a lesser extent, for greater effectiveness, and advancements in computer processing and storage technology therefore brought MRP into existence and influenced its evolution. What started as an efficiency-oriented tool for production and inventory management had become a cross-functional information system serving diverse user groups.

ERP: Overview and Strategic Importance

Where Software Evolution Brought the Present Task Definition of ERP

The addition of ever more functionality and strategic benefits to MRP – in the form of Capacity Requirements Planning, followed by human resource management modules, distribution and financial reporting capabilities – ultimately gave rise to ERP as a comprehensive package software solution that seeks to integrate the complete range of business processes and functions of a firm in order to present a holistic view of the business from a single information and IT architecture (Gable, 1998).

The evolution of ERP has been a decades-long process. What was originally and rather grandiosely termed “ERP” was primarily focused on inventory control. Given that ERP was an offspring of MRP and MRPII, some historians place its origins in the 1960s when ERP systems remained focused on inventory control. Inventory control was important because companies could lose millions on shrinkage and carrying or inventory costs every year. (Ragowsky and Gefen, 2008).

For instance, ERP is the brain child behind large department store inventory control systems that allow merchandise to be tagged and accounted for. While this helped in controlling shoplifting and shrinkage, inventory control was just the beginning of the evolution of ERP. When material resource planning came into being in the 1970s, this became the kernel around which ERP was ultimately constructed.

But this would not have been possible had the majority of businesses globally not acquired computers by the end of the 1980s. With desktop PC’s came networking and distributed terminals that allowed line departments to input updates for decision-makers to access and perhaps act on.

In the view of some, ERP reached its zenith in the 1990s and that today, there are many who view ERP with a jaundiced eye. Nonetheless, ERP has made something of a comeback in the last five years (Stokdyk, 2008). Today interest groups, business, educational faculties and government agencies like forge ahead building networks to integrate their information-gathering and decision-making at a rate that surpasses the expectations of even ten years ago.

Definition: ERP Integrates All Management Resources

ERP systems seek to integrate management of the 4M’s – Manpower, Money, Materials and Machines (Telematica Intituut, 2000). ERP brings all four resources of a business system together so that they are synergized into one complete and total business system.

The different departmental modules of a typical ERP installation report on their own key performance measures and thus aid the company in keeping a closer eye on the totality of its day-to-day operations. At its most extensive, ERP aids a firm in every part of its operation, monitoring the entirety of the value chain from raw material inventory, what is coming off the production line, goods in stock, returns from the trade, accounts payable and receivable, cash in hand, and the company payroll. Thus, ERP potentially addresses almost every aspect of the day to day operations of any given company, educational institute or governmental agency.

Why ERP is Strategic

Decisions to acquire or upgrade an ERP system are not made lightly, considering the cost and investment of time on the part of senior, IT and line managers. Nonetheless, adoption continues apace, justified as it is by broad considerations of enterprise strategy and by hard-nosed cost-benefit analysis.

Many a company management readily agrees to adopt ERP because they believe in the rationale that better planning, integrating the various business areas more tightly, synchronizing decisions with up-to-date information, and optimizing all available resources will grant the business a sustainable competitive advantage (Ammar, 2008) and transform the organization into a more efficient one.

Specifically, the attainable benefits comprise:

- Bringing organizational barriers down by directing information to all those who need it.

- Better coordination across regions and countries for firms operating globally.

- Keeping costs down because the supply chain practices “just in time” deliveries.

- Promoting customer satisfaction by having order status ready to hand.

- More timely decisions and actions.

- Freeing up resources to develop more products or penetrate new markets

- Permitting firmer production, marketing, sales and financial forecasts.

- Raising return on assets by giving decision-makers greater visibility to the interaction between costs and revenue.

Major Components and Architecture of ERP

An ERP system is based on a common database and a modular software design. The common database allows every department of a business to store and retrieve information in real-time. The information should be reliable, accessible, and easily shared. The modular software design means a business should be able to select the modules they need, mix and match modules from different vendors, and customize modules of their own to improve business performance.

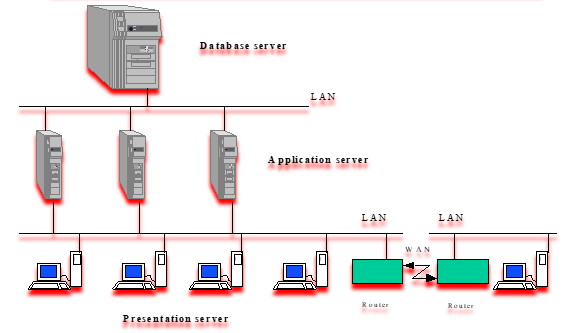

Figure 3 below depicts the core of an ERP system architecture. This is vastly simplified, given the integrative scope of such undertakings. The first clue is that there are multiple application servers and presentation servers, attesting to the variety of applications that have been customized for the firm and the volume of traffic that would not be handled by a single presentation server.

Today, the world has a need to develop ERP software that will allow information to flow freely between societies and global business systems. ERP implementation is a technological breakthrough that is challenging and changing the operations of businesses and organizations around the world. ERP offer a software-based system that handles an enterprise’s total information system needs in an integrated fashion, “Integrative” means that ERP seeks to embrace all aspects of operations within a company from Finance, Accounting, Human Resources, Customer Relations, and Inventory to the end result which is the product or service that the consumer receives.

In the context of adopting ERP, successful strategic planning of incorporates delivery, customization, testing, and implementation or rolling out the system to all end-users within the organization.

An ERP system will include all of the components charted below (Figure 4), the distinguishing characteristic being that they are integrated into one complete system. Research on the success or failure of ERP technology receives global attention since ERP is a major IT investment.

Hence, there is widespread sharing of best practices in implementation and design of ERP systems world wide. There are many companies who have been able to successfully implement ERP technology worldwide and every company who successful implemented ERP technology had at least seven best practice techniques in common. In a survey done in 1997, however, bitter experience ensured that two-thirds of CEO’s believed that there were more drawbacks than advantages to implementing ERP.

The above model represents the dominant progression pattern and implementation steps of ERP.

ERP systems can often be seen as the nervous system or backbone of a company. The ERP systems can perform a great variety of functions that include ordering products or services, materials planning, management of inventory in the warehouse, payables, receivables and other general accounting tasks. The ERP promise of simplicity has led companies around the globe to spend more than $70 billion dollars worldwide for licenses for the software.

It can take a company anywhere from around six months to six years to implant and properly implement an ERP system to a company. Integration is a process that depends on the business and how complex the ERP system is. An ERP system can take anywhere from six month to five years to implement; however, a medium-sized company can expect a mean time of about four years.

Addressing ERP Challenges with Best Practice

According to Welch (2000), there are seven global challenges to the implementation of ERP resource systems around the world. These seven challenges can be addressed by the corresponding seven major best practices.

The above (Figure 4), model represents the best practices in ERP. The companies ensured that all of the company leaders were on board with the implementation. The companies that have been the most successful in the implementation of ERP are the companies that anticipate that changes will be part of their plan and development strategy. The basic tool for a successful ERP architectural system to succeed is to the ability to have a well mobilized and engineered plan that can be adjusted and accept changes throughout the project.

The team must be able to make a commitment to insure that the ERP systems can handle the changes that will be a part of early, middle and late stages of ERP implementation. The company must be on the same page because the fiscal spending for a typical ERP project can run into millions of dollars. In the ERP system that was most successful four Key factors were seen in the majority of research.

- One senior executive took accountability for each project milestone by assigning tasks to managerial staff and rewarding staff with bonuses when goals were achieved.

- The company generally set aggressive, but achieved goals the goals were simplified so that employees could see a clear small picture rather than a huge ERP objective.

- In successful companies each ERP goal was different and the business task that each goal would perform was clear.

- The financial impact was clear the exact cost of each goal was clearly marked. Source: (Welch, 2000)

The second major success of a company’s ERP implementation depended on the right of the governance of the given model that the company hoped to establish. Third the company was responsible for implementing and visualizing the transformation that the ERP system will make on the overall business. Fourth the business must make sure that it can ensure that there will be ongoing level of support and that the support is organized so that no unexpected problems arise in implementation.

Fifth the needs of the organization must be met in terms of ERP implementation this means that research must be done to determine the extent of the ERP system. The company must be extremely specific on what they want to achieve from their ERP system. The sixth and seventh best practices are to always be keen on the business goal and to manage to the ERP system constantly. The ERP system will not manage itself in the early stages of development.

According to Rego (2007), Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) integrated application software systems and Automated Data Collection (ADC) tools are experiencing an uptrend in use. In part, this is due to legislation that encouraged both Canadian and United States companies to acquire one or both applications to meet business needs and financial reporting requirements.

All in all, ERP systems are well-established IT application in today’s medium to large multi-national organizations. They have evolved into fully integrated supply chain tools, including customer relationship management (CRM), business-to-business transaction support, vendor-managed inventory tools and customer self-service interfaces and portals.

The ERP Vendors and Their System Packages

The available ERP products and systems all come from a fairly limited set of companies: SAP, Oracle, PeopleSoft, Microsoft and about two dozen secondary competitors. One of the latter is Taiwan’s Acer group, long a respect name as computer OEM maker and currently looking to leverage global presence of its own server, desktop and laptop lines as penetrate the ERP systems market.

Early on, these companies were struggling affairs, wobbly legs and unstable. Consequently, software developers chose to automate only the most computation-intensive (i.e., labor-intensive) activities. Between the early days of computing and today’s business environment of crippling resource constraints, however, ERP integrators received the boost they needed to grow.

Germany’s SAP is the pioneer and its core product line, SAP R/3 (for release 3), the most widely-used and highly regarded ERP system bar none.

In 1991, PeopleSoft, Inc. was the first company formed around the nomenclature of providing ERP systems. Later acquired by Oracle, PeopleSoft was a company that provided human resource management systems (HRMS), customer relationship management (CRM), Manufacturing, Financials, Enterprise Performance Management, and Student Administration software solutions to large corporations, governments, and educational institutions.

In the beginning, the PeopleSoft product line was built around Client-Server architecture. Round about the release of People Soft 8, however, the entire software suite was shifted to a web-centric design called Pure Internet Architecture (PIA). The new format allowed all of a company’s business functions to be accessed and run on a web client. Originally, a small number of security and system setup functions still needed to be performed on a fat client machine; however, this is no longer the case. The inherent nature of Internet-based applications allowed for a straightforward transition from a client-server model. One important feature of PeopleSoft’s PIA is that no code is required on the client there is no need for additional downloads of plug-ins or JVMs such as the Jinitiator required for Oracle Applications.

The architecture is built around PeopleSoft’s proprietary PeopleTools technology. (Development platform similar to a 4GL). PeopleTools includes many different components a developer needs to create an application, including a scripting language called PeopleCode, design tools to define various types of metadata, standard security structure, and batch processing tools. The metadata describes data for user interfaces, tables, messages, security, navigation, portals, and so forth.

The benefit of creating their own development platform allowed PeopleSoft applications to run on top of many different operating systems and database platforms. Currently, it is not tied to any specific database platform. PeopleSoft implementations exist or have existed on Oracle, Microsoft SQL Server, Informix, Sybase, and IBM DB2.

Aside from acquiring PeopleSoft, Oracle itself had already furthered the evolution of ERP. Independent analysis of marketing and promotional materials (e.g. Bern, 2008) revolved on four categories of benefit end-users could derive:

- Improved coordination between various departments within a business, making them much more productive and hence, generating operating efficiencies and cost savings.

- Manage day to day business matters more effectively. This is premised on gaining visibility to real-time performance reports.

- More rapid transfer of crucial information from one section of the business to another. This means that responding to anything of importance can happen more quickly and this raises the overall effectiveness of the organization.

- All of the above benefits ultimately have to do with more timely and better-informed decisions.

Oracle advanced rapidly after taking over PeopleSoft to become the largest and most powerful company in the industry. At the height of the ERP revolution Oracle was working round the clock.

Such are the cash flows generated by ERP projects that many a team of systems developers have, through the years, set themselves up as Oracle clones. One of these companies was Siebel which lasted only a few years.

On the other hand, robust revenues have also attracted ERP offerings from other IT sectors. There is IBM Business Solutions, for instance, evolving from decades-long core competence in hardware to continue the diversification into knowledge process outsourcing and consulting on solutions.

Nor has PC platform inventor Microsoft been immune to the attractions of the ERP business. At Redmond, Microsoft brought together four product lines under the ERP umbrella, rather ambitiously promising that licensees would receive supply chain management (SCM), customer relationship management (CRM) and business analytics on top of core financial management functionality. And yet, the recommended “suite” is heavy on financial reporting.

- Great Plains® for financial management – across industry segments, for midmarket businesses, with extraordinary out-of-the-box functionality and a broad set of add-on solutions.

- Axapta® — supports advanced manufacturing and supply chain management for the upper midmarket segment and for divisions of large organizations or multinationals.

- Navision® — financial management for the lower midmarket to midmarket segments, customizable for local market practices.

- Solomon – with features similar to Great Plains

In common with many competitors in the business, marketing appeals for ERP integration tout “customer-centric technology themes” that the ERP products will center on moving forward: Best Total Cost of Ownership, Adaptive Processes, Empowered Users, Connected Business and Insightful (Microsoft Business Solutions, 2004). One notes that, far from talking up product and system features, the company markets on the basis of customer need.

ERP in Action: The Perspective of the End-User Firm

Success Factors in Implementation

A canvass of the literature on ERP implementation (e.g., Holland et al., 1999; Sarker and Lee, 2003; Rosario, 2000) reveals that there are at least seven distinct groups of success factors:

- Business plan and vision (essentially meaning leadership)

- And this is related to senior management conviction and active support

- Change management styles

- Quality of top-down and down-up communication

- The departmental composition, skill sets and incentives put in place for the ERP implementation team

- Quality of project management itself

- System analysis and technical implementation.

Employing case studies of a firm that had adopted ERP for the first time and another that embarked on an upgrade, Nah and Delgado (2007) suggest that the impact of such success factors vary according to implementation phase. Employing the concise four-phase model of Markus and Tanis, the team showed that the leading success factors were quite similar, though varying substantively, as implementation progressed:

Industrial Sectors That Benefit

Were the ERP vendors to be believed, such versions as SAP R/3 would be deployed across the board as a “one size fits all” solution regardless of industry or situation. This is “horizontal integration”. But the industry has matured to the point where vendors admit that there are customization lead times and costs involved in embracing ERP. Hence, Linthicum (2008) asserted, the concept of horizontal integration applies solely to fundamental process or network components such as the goal of transformation, routing hardware, or the need for flow control and adapters.

What has emerged, more logically, is specialization by industry or “vertical integration”. This makes more sense, given the disparate resource mix, threats, standards and opportunities characteristic of, say, health care, CRM, financial services, education, a law practice, or logistics as opposed to the manufacturing world that initially accepted ERP so warmly. Examples of similar integration imperatives owing to externally-imposed or commonly accepted standards are:

- The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) that protects insurance coverage of workers when they switch jobs. Among other things, this U.S. law mandates the use of electronic data interchange in the health care vertical at all levels.

- For retailers, UCCnet is concerned with the supply chain and is based on the universal product codes imprinted on bulk packs and individual packages.

- In the high-tech (IT, E-commerce) sector, there is RosettaNet that purveys PIPs and enforces standards for transaction-centred data exchanges.

Other research, including one by Stratman (2007) suggests that ERP systems and firms that operate under heavy manufacturing fall into basic strategic groups in order to get the task completed. These groups are variously characterized as caretakers, marketers, innovators, defenders, and analyzers (Figure 5).

Firm Size

Given that the market of large, globally-operating firms is close to saturation and is in any case hotly contested by every ERP integrator, rivals SAP and Microsoft have adjusted their marketing strategy to target new geographic markets (the up-and-coming BRIC nations, for instance: Brazil, Russia, India and China) or medium and small-size businesses. Size is relative, true, but it is revealing that SAP defines “small business” as equivalent to annual revenues of $1 billion or less.

Mid-sized Aberdeen Group, for instance, typify themselves as part of the “largely underserved and fragmented global midmarket segment” (cited in Microsoft Business Solutions, 2004). Beyond a certain uniformity in financial reporting that national and continental reporting standards permit, Aberdeen Group is grateful for evidence that an ERP systems integrator recognizes and customizes modules according to the industry, unique requirements and situation of smaller firms.

The ERP System Today

Opportunities Leveraged

Case studies of successful ERP implementation reveal that one of the most fundamental requirements are the expectations of, and support given by, senior management.

The goal of contemporary ERP systems is focused on streamlining and integrating operational processes and the flow of information within a company that promotes cooperation, coordination, synergy (Nikolopoulos, Metaxiotis, Lekatis, & Assimakopoulos, 2003) and ultimately, greater organizational effectiveness. Given that the latest versions of many ERP systems have expanded beyond the back office to promote the efficiency of front-office activities (e.g. CRM), firms implementing ERP evidently seek to sweep away the smorgasbord of departmental systems that could not even communicate to each other with a single integrated system that does it all faster, better, and cheaper.

The Hidden Story of Failure

Unfortunately, the shining promise of “business and technology integration technology in a box” (Koch, 2005) has also very often not been fulfilled. While there are some success stories, many companies devote significant resources to their ERP effort only to find the payoff disappointing (Dalal, Kamath, Kolarik,& Sivaraman, 2003; Koch, 2005).

While ERP consultants can be faulted for deficient planning and erroneous force-fitting of non-customized solutions, the plain fact is that IT systems are subject to unpredictable events that are, by definition, outside the control of either the ERP consultant or the end-user: requirements change because the marketplace changes, competitors change, parts of the design are shown wrong by experience, people learn to use the software in ways not anticipated. Notice that frequently the unpredictable event is about people and society rather than about technical issues. Such unpredictable events lead to the needs of the parts which must be comfortably understood so they can be comfortably changed.

The Evidence for Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Contrary to the popular view, ERP is not a magic wand that one waves to generate competitiveness for a business enterprise. Prior to even planning an ERP purchase and implementation, a company should be prepared and competitive in order to make optimal use of ERP.

“Sustainable advantage comes from systems of activities that are complementary. These “complementarities” occur when performing one activity and gives a company not only an advantage in that activity, but it also provides benefits in other activities.” -Michael E. Porter.

One way to frame the justification for the above statements is, what if SAP A.G. with its vaunted skill in manufacturing, were to somehow succeed in convincing all European manufacturers to adopts its S3 software? If S3 was the magic bullet, all manufacturing customers would gain a measurable boost in competitive advantage. But everybody would wind up in the same relative position as before, albeit having moved forward a step at considerable expense.

Rather, companies obtain sustainable advantage by pursuing excellence in at least one of three areas (and if at all possible, very good at the other two):

- Product differentiation: Rolls Royce, Daimler Benz and BMW acquired sustainable advantage not by producing cheap, fuel-efficient compacts as Toyota does but by designing powerful and durable vehicles.

- Customer service: Call center agents in India are dirt-cheap but Filipinos have durable competitive advantage in being friendlier and bridging the cultural divide with American callers by at least two orders of magnitude.

- Operational efficiency: Crude oil reserves in the Caribbean island-nation of Trinidad and Tobago have fallen since 1982 but the government offered power-intensive manufacturers (e.g. aluminum smelters) affordable rates in a special economic zone where pipelines for the fourth-largest supply of liquid natural gas in the world all converged. Result? A ready market for LNG and more employment in what is otherwise a resource-poor nation.

Hence, the real path to sustainable competitive advantage is to pursue one of the above strategies and then select the software vendor and system package that will support that strategy.

Conclusions

This review of the literature on ERP has enabled the researcher to place this class of system product in its proper historical perspective, to understand the fit with enterprise strategy seeking sustainable competitive advantage in the marketplace, and gain visibility to the operational requirements that impel firms to invest in ERP.

Notwithstanding its origins in Material Resource Planning, in optimizing manufacturing and resource inventories, enhanced ERP exists precisely as a stable, timely and dispersed tool for management decision-making. It is stable because vendors tout integration: one code base and one platform for an extensible range of departmental modules. ERP is dispersed because user firms have realized just how vital it is to collate performance metrics from production, procurement, warehousing, distribution, finance, marketing and HRD. And it is timely because ERP systems operate in real time, accepting new data, updating databases and making available management reports immediately rather than at the end of the month, quarter or fiscal year.

To date, we have seen how empirical research in this area has covered at most a ten-country sample frame in a European study of cross-cultural adoption rates. More often than not, field studies have focused on one market (e.g. ERP adoption among firms of various sizes in Tunisia) or case studies on a limited number of firms.

Given a business milieu likely to remain adverse for the time being, there seems to be scope for:

- Updating the state of knowledge about the rationale for adopting ERP;

- Being comprehensive by taking into account operational effectiveness and end-user satisfaction in every operational area of the firm covered by an ERP implementation.

- Testing the hypothesis that operational effectiveness and limitations apply across departments within the firm, by firm size, across industries, national borders and cultural barriers.

Research Plan

Aims and Objectives

The aim of this study is to contribute to the growing body of knowledge in this field by critical examination of the strategic role ERP systems play. In scope, the study will commence with exploring the theoretical foundations underlying Strategic ERP systems as implemented globally, continue to a scrutiny of the inherent strengths and weaknesses pertinent to this category of IT systems and analyze near-term prospects. We shall develop a vision of the outlook for ERP via an in-depth understanding of growing demands of IT systems; how success or failure is linked with corporate culture and leadership styles; and identifying critical success factors.

Subsequently, the objectives of the study shall cover:

- To develop a holistic view of strategically managing the acquisition and deployment of an ERP system via an authoritative review of the literature, buttressed by an empirical field investigation using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods.

- To explore the case study approach for a synthesis of the dominant success factors for an ERP implementation.

- To highlight the major challenges commonly encountered when acquiring, implementing and maintaining ERP systems.

- To critically investigate successes and drawbacks by firm size, implementation strategy, markets or countries, centralized versus decentralized organizational management.

- To extract best practices and other recommendations for those planning for, or already making a career of, consulting for ERP implementation.

The Range of Methodology Options

In light of the stated objectives, the research process for this study shall proceed as shown in (Figure 6). Having already done an exhaustive review of recent literature to this point, we shall now craft the research design and assess the methodology options.

Given the time constraints imposed on academic research, the appropriate research design in this case is that of a post-hoc, cross-sectional study of the universe of firms that have implemented ERP. To assure sufficient grounds for post-hoc evaluation of an ERP deployment, we recommend that only organizations that have already passed at least the first-year mark since full rollout should be included in this study.

For a cross-sectional study, the methodology options cover: case study, qualitative depth interviews, qualitative focus groups, content analysis of published reports, quantitative customer satisfaction surveys, and secondary research on corporate performance.

Recommended Field Survey Methodology

As we have seen, ERP is not without its strong adherents and detractors. Where feelings are strong and emotions run high, it is always advisable to maintain objectivity. Since this study is concerned with strategic issues that confront firms operating globally – homogenous companies with differing national origins and heterogeneous firms that count multi-cultural staff – the issue of test/re-test reliability gives primacy to quantitative methods.

On the other hand, one must also be pragmatic about issues of proprietary information, competitive advantage and corporate IT staffs feeling slighted about implementation hurdles or outright systems failures. Hence, provision must be made for closing the gap by obtaining qualitative feedback or anecdotal evidence.

Hence, one proposes that the core research method of a large-scale customer satisfaction survey be supplemented by:

- Case analyses, both published and sourced from the ERP integrators themselves.

- Depth interviews with a selection of information gatekeepers or key opinion leaders.

- Analysis of financial performance, most readily available for ERP-using firms listed on the stock markets of their respective countries.

Study Instrument

The quantitative Departmental End-user and Customer Satisfaction Inventory (DECSAT-I) shall be formulated by the author based on the more robust and theoretically sound items of internal end-user post-deployment surveys in respect of ERP. The most likely information areas are:

After suitable pilot tests, the questionnaire shall be administered as an online survey. Online administration is entirely logical since Internet access can be presumed at the level of all decision-makers (see details in Sampling Frame below) of a firm that already implements Web-based ERP. Secondly, an online survey grants the researcher seamless access across national boundaries, a vital consideration for an investigation of global conditions. Thirdly, the online format is more cost-effective in point of “fieldwork time” and data-entry lag time (since many online survey services do running tallies in formats suitable for popular spreadsheets and statistical software).

Market Coverage, Sample Frame and Sample Size

The survey shall be global in scope, sampling the Fortune 1,000 (and their national equivalents) in the United States, Canada, Europe, the Middle East, South and East Asia. The rationale for multi-country coverage is based on the work of Van Everdingen and Waarts (2003) and others pointing out that there are cultural and IT adoption differences that impact the penetration of ERP and other technologies across nations with comparable stages of economic development.

In the “Eurozone”, the likely country coverage shall be Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Russia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Mideast coverage shall likely comprise Turkey, and such members of the Gulf Cooperation Council as Saudi Arabia, Dubai, Kuwait and UAE. In South Asia, Pakistan and India will be part of the study. Finally coverage in the rest of Asia shall embrace South Korea, Japan, the Republic of China/Taiwan, Hong Kong, mainland China, the Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand.

In both the United States and Germany, where ERP penetration is hypothesized to be higher than average globally, we propose to solicit participation from a minimum of 400 companies classified as either large or mid-size in operations and revenue. For all other countries, the mail-out count by company shall be 200 each. In total, participation shall be solicited from a total of 6,600 companies, an unknown fraction of which may or may not be ERP adopters.

Within each company, we propose to solicit participation from a minimum of five target respondents:

- CEO’s for their high-level view of the investment in ERP and resultant operating benefits

- CIO’s for a more technical appreciation of alternative integrators and systems

- One each from IT, manufacturing and finance since these are the “core sections” around which ERP integration usually revolves. The more fully-integrated a company is, the more departments and target respondents will be obtained.

Popular listings such as the Fortune 1000 or the Financial Times 1000 shall be the source for names of top-level executives. Assistance of the Human Relations or Employee Relations Departments shall be vital, however, in securing referrals to departmental-level sources. Once contact is made at this level, response bias is obviated by the fact that respondents can encode their satisfaction ratings online without need of clearance with, or observation by, other company staff.

Owing to the voluntary nature of this survey, accomplishment rates will likely be low. I have rejected the option of offering an incentive (a drawing, say, for a $500 gift check) as unnecessary in view of the interest that ERP implementation is presumed to have provoked among the key staff whose cooperation is solicited.

Data Analysis Plan

The data shall be subjected to:

- Cross-tabulation by company size, region, country and cultural dimensions (the macro, meso- and micro-level factors) predicted in the (Figure 7) model overleaf (Morden, 1999; Hofstede, 2001).

- ERP penetration and satisfaction levels explained by national culture variables.

- Inter-correlation matrix among the key independent and dependent variables.

- Logistic regression analyses against the dependent variables adoption and satisfaction.

Table 1: Characteristics of companies with low / high scores on the Hofstede dimensions and the expected influence on the adoption of innovation (Hofstede, 2001)

Table 2: Low- and High-Context Countries and Their Characteristics.

N.B. Adapted from Van Everdingen and Waarts, 2003.

Bibliography

Algeo, M. E. A. & Barkmeyer, E. J. (2008) An overview of enterprise resource planning systems in manufacturing enterprises. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Web.

Ammar, S. A. (2006) ERP – A rising need of enterprises. WebProNews. Web.

Bennett, S. (1999) All systems go! Works Management: Manufacturing into the Millennium, pp. 68-69.

Bern, D. (2008) A bit about Oracle ERP. Ezinearticles. Web.

Chung, S. and Snyder, C. (1999) ERP initiation – A historical perspective. Proceedings of the Americans Conference on Information Systems (AMICS), Milwaukee, WI.

Dalal, N.P., Kamath, M., Kolarik, W.J., & Sivaraman, E. (2004) Toward an integrated framework for modeling enterprise resources. Communications of the ACM, 47(3), pp. 83-87.

Emery, D. R., Finnerty, J. D. & Stowe, J. D. (2007) Corporate financial management. New York: Pearson Education.

Farmer, D. (1985) Materials management handbook. Aldershot, Gower.

Gartner Inc. (2007) Magic quadrant for ERP service providers: North America. Web.

Gattorna, J. & Day, A. (1986) Strategic issues in logistics. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 16 (2) pp. 3-42.

Goddard, Walter E. (1990) MRP II helps drive Rolls-Royce. (Manufacturing Resource Planning) (JIT/MRP II Report). Modern Materials Handling.

Gold, L. (2007) SAP charges towards small and midsized market. Accounting Today, pp. 20-22.

Gumaer, R. (1996) Beyond ERP and MRP II. IIE Solutions, 28(9), pp. 32-35.

Gupta, A. (2000) Enterprise resource planning: The emerging organizational value systems. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 100(3), pp. 114-118.

Hall, E.T., 1976. Beyond culture. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press.

Hodson, W. (1992) Maynard’s industrial engineering handbook. New York, McGraw-Hill Inc.

Holland, C. P., Light, B. and Gibson, N. (1999) A critical success factor mdoel for enterprise resource planning implementation. Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Information Systems, Copenhagen, Denmark, pp. 273-297.

Hofstede, G., 2001. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Sage Publications, second edition.

Johnston, J. (2005) VSE: A look at the past 40 years, Z Journal, Thomas Communications. Web.

Kumar, K. and Hillegersberg, V. (2000) ERP experiences and evolution. Communications of the ACM, 43(4), pp. 22-26.

Lehman, M. M. (1980) Programs, life cycles, and laws of software evolution”, Proceedings of the IEEE, pp. 1060–1076.

Linthicum, D. (2008) What is the difference between horizontal and vertical integration? TechTarget. Web.

Kahn, M. (2004) The beginning of I.T. civilization – IBM’s System/360 mainframe. The Clipper Group Inc. Web.

Koch, T. (1996). The message is the medium: Online all the time for everyone. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Koch, C. (2004). Koch’s IT strategy: The ERP pickle. Web.

Markus, M., Tanis, C., & Fenema, P. (2000) Multisite ERP implementation. Communication of the ACM, 43(4), pp. 42-46.

McGaughey, R. E. & Gunasekaran, A. (2007) Enterprise resource planning (ERP): Past, present and future. International Journal of Enterprise Information Systems, 3(3) pp. 30-43.

Microsoft Business Solutions (2004) Microsoft Business Solutions showcases ERP strategy and road map: Customers benefit from five development themes and ongoing product investments. Microsoft Corp. Web.

Morden, T. (1999) Models of national culture – A management review. Cross Cultural Management 6 (1) pp. 19-44.

Nah, F. F. & Delgado, S. (2006) Critical success factors for enterprise resource planning implementation and upgrade. The Journal of Computer Information Systems 46 (5) pp. 99-113.

Nikolopoulos, K., Metaxiotis, K., Lekatis, N., & Assimakopoulos, V. (2003) Integrating industrial maintenance strategy into ERP. Industrial Management + Data Systems, 103, (3/4), pp. 184-192.

Orlicky, J. (1975) Materials requirements planning. NY: McGraw-Hill.

Plossl, G. (1994) Orlicky’s material requirements planning. New York, NY, McGraw-Hill.

Ragowsky, A. & Gefen, D. (2008) What makes the competitive contribution of ERP strategic. Database for Advances in Information Systems. 39 (2) pp. 33-49.

Rego, R. (2007) CMA management. Hamilton: 80, (8) pp. 19-21.

Rosario, J. G. (2000) On the leading edge: Critical success factors in ERP implementation projects. Business World (Philippines), p. 27.

SAP (2008a) SAP history: From start-up software vendor to global market leader. Web.

Sane, V. ( 2005). Enterprise resource planning overview. Ezine articles. Web.

Sarker, S. & Lee, A. (2003) Using a case study to test the role of three key social enablers in ERP implementation. Information and Management, 40 (8) pp. 813-829.

Sarkis, J. and Sundarraj, R. (2000) Factors for strategic evaluation of enterprise information technologies. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 30(3) pp. 27-36.

Schwartz, E. (2007, April 10) Does ERP matter – industry stalwarts speak out. IT World Canada, InfoWorld (US). Web.

Shtub, A. (1999) Enterprise resource planning (ERP): The dynamics of operations management. Norwell, MA, Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Smolik, O. (1983) Material requirements of manufacturing. New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Stokdyk, J. (2008) ERP – Evolution of a computing acronym. FinanceWeek. Web.

Stratman J. K. (2007) Realizing benefits from enterprise resource planning: Does strategic focus matter? Muncie, 16(2) pp. 203-216.

Taylor, F. W. (1911) The principles of scientific management. New York: Harper Bros. pp. 5-29.

Telematica Instituut (2000) ERP, XRP & EAI _in virtual marketplaces. Web.

Turbid, T. (1990) What every manager needs to know about MRP. Manufacturing Engineering, 8 (1) pp. 46-48.

U. S. Department of State (2008) The post war economy: 1945-1960. Web.

Vollmann, T., Berry, W., & Whybark, D. (1992) Manufacturing planning and control systems. 3rd ed., London, Irwin Professional Publishing.

Van Everdingen, Y. M. & Waarts, E. (2003) A multi-country study of the adoption of ERP Systems. ERIM Report Series Reference No. ERS-2003-019-MKT.

Welch, Ivo. 2000. Views of financial economists on the equity premium and on professional controversies. Journal of Business, 73: pp. 501-537.