- Introduction

- Theory of Reasoned Action

- Limitations to the Theory to TRA

- Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

- Limitations to the Theory of Planned Behaviour

- The Health Belief Model (HBM)

- Limitations to the Health Belief Model with Regard to the TRA

- Justification for the TRA for this study

- References

- Appendix 1

Introduction

The research undertaken for this study examines the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of oncology nurses as related to the management of pain in the clinical oncology setting. In the nursing context, there are various beliefs related to pain management that may influence nursing decisions. Identifying those beliefs and the influence on their nursing actions allows this research to work out a certain nursing policy. In this respect, it is necessary to identify reasons of nurses’ action. In order to examine their knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, we needed to discover the tools that allow us to investigate that. There are a number of theories, such as Health Beliefs Model, the Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behaviour, etc. In this respect, TRA was selected because it is aimed at predicting the influence of a number of human and social factors on behavioural intention, attitude and behaviour. Behavioural intentions, therefore, are immediate antecedents of behaviour, selling information beliefs about the likelihood of performing that behaviour. Interpreting this, beliefs, being antecedents of behaviour, are identified to behavioural enormity of sense, the underlying influence on a person’s attitude, and behavioural beliefs. Thus, we apply to the TRA because it allows us to define the individual attitude toward pain relief; we also refer to the tool because it is related to behavioural beliefs.

In the TRA, intention is what really determines the behaviour of an individual; unintended actions do not fall under the theory. As pain management is considered an “intentional” activity, this conceptual framework will guide this study which will inform the development of nursing policy related to pain management practices. Individuals are rational, and information they have about certain behaviour is very important in determining how they behave. This study, therefore, explains the relationship between attitude and behaviour using both dependent and independent variables, which are attitude, beliefs, behavioural intentions and behaviour. The dependent variables in this study have been identified as behavioural intention and behaviour, while the independent variables are attitudes toward behaviour and subjective norms.

In order to understand patient’s beliefs shaping their attitude toward behaviour, nurses should refer to the main attributes forming intention behaviour concerning pain management. In this respect, because behavioural intention is formed as a combination of person’s attitude along with subjective norms, which is perceived expectation from the individuals that a patient respects, nurses engaged in pain management should know whether patients’ attitude are based on negative or positive beliefs (Eagly & Chaiken, 1995). In other words, nurses should define the antecedents of belief shaping their behavioural intention.

At this point, Sasane (2008) states that attitude toward behaviour is premised on behavioural beliefs and evaluation of behavioural consequences. In this respect, the specificity in attitude evaluation was necessary to define behaviour precisely. Fishbein (2008) has stated, “…external variables such as cultural differences, moods, and emotions and differences in a wide range of values should be reflected in the underlying belief structure.” (p. 840). Regarding person’s beliefs concerning pain beliefs, some people from Asian countries, including Saudi Arabia and China, hold the belief that medication should not be used to relieve pain (Glanz et al., 2008, p. 103). In this respect, beliefs can be a result of social and cultural norms existing in different counties. Judging from these assumptions, attitudes cannot be considered as purely negative or positive because they depend on a mixture of cultural, moral, and social aspects.

Regarding the cultural determinants, nurses should also possess knowledge of cultural and social aspects and contexts influencing patients’ attitude to pain management. It is argued that knowledge about behaviour influences nurses’ attitude. Possessing necessary background knowledge about patients’ beliefs allows nurses to build an effective nurse-patient communication that would provide greater mutual understanding, patient satisfaction, and patient involvement in decision-making. For instance, a nurse can alleviate emotional stress by telling a patient that the results of diagnosing are normal. Alternatively, a nurse can provide clear explanation to help patient experience lower levels of distress and improve his/her sleep and appetite. Effective communication, hence, is possible if a nurse possesses sufficient knowledge about patients’ attitudes that affect their behaviour. Nurse’s knowledge, attitudes and beliefs towards pain management make it necessary to set policies that will help improve the nurse’s pain management. This research will be used to develop pain management policies in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Theory of Reasoned Action

The theory of reasoned action (TRA) was introduced by Fishbein (2008) in the 1960s to predict behavioural intention, attitude and behaviour. The theory claims that the intention of an individual determines their behaviour. The intention of a person behaving in a certain manner is a function of their attitude towards that behaviour and the person’s subjective norms or the person’s belief in relation to the activity. In this theory, intention is the important predictor of behaviour. Intention is the immediate precursor of behaviour and shows the person’s readiness to behave in a particular manner. In this theory, only two things determine the intentions of an individual to behave in a certain manner. These are attitude and subjective norms. Subjective norm is the perception of an individual about whether the people around them think the individual should perform the behaviour. It is through the opinions of others that an individual feels motivated to practise behaviour.

Apart from beliefs about outcomes of performed behaviour, a person’s attitude is also premised on person’s evaluation of those consequences. In other words, people analyse potential outcomes a specific behaviour will have for his/her health. Based on this assumption, Miller (2005) exemplifies that a person might have a set of beliefs that are have a positive correlation. For instance, some people belief that an exercise has a positive influence on health because it helps them look good and attractive whereas others believe that exercise is useless because it is very time-consuming. Regarding the above, patients’ refer to a causal relation to outline whether consequences are negative or positive. Similar to Miller (2005), Belleau et al. (2007) refer to the TRA and attains much importance to engaging evaluation of behaviour into assessing the behaviour intention. It is an inherent components a person’s decision either to perform or not perform a specific action.

The Theory of Reasoned Action can help provide evidence based information that will inform development of policies since it has been identified by Azjen (1991) as providing a clear understanding of human behaviour. The model can be simplified to mean that the intention that is determined by attitude determines the behaviour of an individual. The concern about behaviour can be determined by a suggestion that there are outcomes that “come from a certain behaviour” and “evaluation of those outcomes” (Ajzen, 1991). For example, nurses may believe that by administering pain relief, the pain reduces and the patient feels better, which will lead them to administer the pain relief (Ajzen, 1991). In addition, Ajzen (1991) suggests that the individual looks at what others think about the behaviour and what they want them to do (subjective norm). The individual is then motivated to either behave in a certain way or not (motivation) (Ajzen, 1991). Theory of Reasoned Action is, therefore, used as a tool to identify the attitudes, along with subjective norms to help address the issues that relate to behavioural beliefs since it allows people to identify the individual attitude towards pain relief. Based on the TRA, the issues related to behavioural beliefs such as nursing practice in pain management can be addressed (Ajzen, 1991). The TRA, thus, explains the limiting factors on attitudinal influence through the separation between behaviour and behavioural intentions (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

Behavioural intention is defined as an individual’s intention to behave in a certain manner. The thoughts of an individual towards behaviour influence their attitudes towards behavioural intention and behaviour. Attitude drives one into behaving in a particular way. For example, if the nurse has an attitude that pain relief should not be administered, the nurse will practise that behaviour will never consider it right to administer pain relief. In addition, a nurse should also possess knowledge; external information flows about patients’ cultural and social background, to define in what way pain can be managed. Such a perspective identified subjective norms.

This Theory of Reasoned Action involves social influences so that it can be used to examine how societal norms influence the behaviour of the nurses towards pain management. For somebody to make a decision, the many available options are evaluated by them, depending on the strength of the conflicting pressures (Fishbein, 2008). For example, a nurse will decide to give pain relief to an old patient depending on patient’s belief about pain relief, the norms of the society regarding giving pain relief and the nurse’s attitude. This means that the behaviour or consequence related to pain relief in this example is determined by beliefs, societal norms and attitude.

Limitations to the Theory to TRA

The Theory of Reasons Action can be effective for certain situation only. IN particular, evaluation of behavioural intention will predict the behaviour of a volitional act, in intention prior to performance meet the behavioural criteria regarding action, context, target and time (Sheppard et al., 1988). In this respect, there are three limiting aspects regarding the use of subjective norms and attitudes, as well for using behavioural intention to predict the behaviour (Sheppard et al., 1988). First, there should distinction between goal intention and a behavioural intention. Second, a choice can also change the character of intention, as well as the role of behavioural intention in performing behaviour (Sheppard et al., 1988). Finally, there is an evidence difference between what a person intend to do and what he/she actually plant to do.

More studies are needed to investigate the additional component of perceived behavioural control over behaviour to show its reliability. The component of attitude in this theory shows that behavioural outcomes are determined by the beliefs about the outcome of the action without providing a guide to the important beliefs societal norms that will vary from context to context (Glanz et al., 2007). For example, in this study, the theory does not give standard beliefs that will help formulate policies since different cultures have different beliefs which may be opposite to those held by another different culture (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). While the theory has been used in behaviour determination with different professionals such as health providers, it does not provide cues for the proper component to predict behaviour. The theory has a significant limitation, which is the assumption that behaviour is under volitional control (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) shows how attitude and behaviour are linked. This theory was authored by Icek Ajzek as a continuation of the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen, 1991). TBP is an extension of the TRA and includes an additional component of “perceived behavioural control”. In this theory, action does not require reason and consciousness, thereby accommodating non-intentional behaviours. This theory expands on the assumption that behaviours are only volitionally controlled. The self-efficacy component in the TPB is therefore the most important component to behavioural change. Behavioural intentions that lead to behaviour are then determined by the attitude towards the behaviour, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control, which is not tested in the current study (Armitage & Conner, 2001). In the Theory of Planned Behaviour, as opposed to the Theory of Reasoned Action, perceived behavioural control is a component added to determine behavioural intention and behaviour. In this respect, there is the necessity to distinguish between intentional behaviour and actual behaviour. To enlarge on this point, Ajzen (1991) proposes that circumstantial limitations prevent behavioural intention from leading to actual behaviour. Because behavioural intention cannot be considered a determining factor to perform behaviour due tot he incompleteness of the individual control, Ajzen (1991) introduces “perceived behavioural control”. Such behaviours are not straightforward and may be under non-volitional control. In this study, the nurse’s practices are volitional and only few constraints if any exist, thereby disqualifying the use of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. The study will use the theory of reasoned action, because pain management is volitionally controlled and never accidentally done (Godin & Kok, 1996). Additionally, more studies are needed to investigate the additional component of perceived behavioural control over behaviour to show its reliability (Armitage & Conner, 2001).

Limitations to the Theory of Planned Behaviour

As it has been discussed above, perceived behavioural control is the third element influencing behaviour intention, as presented in the Theory of Planned Behaviour. In order to define the major differences between the TPB and TRA, several testings should be considered. At this point, Madden et al. (1992) have tested two hypotheses. The first stated that the introduction of perceived behavioural control would greatly advance the prediction of behavioural intentions. The second hypothesis posited that prediction intensification of target behaviour would be associated with the extent of perceived behavioural control. The researchers have concluded that the TPB provided more variation as compared with the TRA. Thus, “increased precision in the prediction of intentions and target behavioural control could be achieved by assessing perceived behavioural control over the behaviour” (Madden et al. 1992, p. 9). As a result, it is purposeful to formulate the strategies that change intentions through altering perceptions of control. As per the second hypothesis, the results have also approved the contribution made by perceived behavioural control. Specifically, low level of perceived control, target behaviour was not controlled by intentions. In contrast, high level of perceived control blurred the differences between perceived behavioural control and behavioural intention. In this respect, it is rational to state that perceived behaviour can provide pertinent information for predicting behavioural intentions.

Regarding the above-presented testing, certain differences should be identified between the TPB and TRA. First, person’s attitudes are affected by perceived behavioural control, which means that certain pressures have a potent impact on anticipated behaviour. The newly emerged concept of perceived behavioural control derives from self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997). Thus, according to Ajzen (1991), self-efficacy is defined as a “conviction that an individual can perform the behaviour to produce the results”. In this respect, the outcomes expectancy is associated with a person’s evaluation that a specific behaviour can lead to particular outcomes. Self-efficacy theory is important for defining the difference between attitude, intentions, and behaviour and, thus it is often applied in various health-related fields (Ajzen, 1991).

Unlike the TRA, that is more premised on social factors and external variables (subjective norms), the TPB is associated with personal analysis of person’s awareness of his/her abilities. This awareness is based on non-volitional behaviour that is not covered in the Theory of Reason Action. Nevertheless, both theories – the TRA and the TPB – can explain a person’s social behaviour as far the social variable is concerned.

The Health Belief Model (HBM)

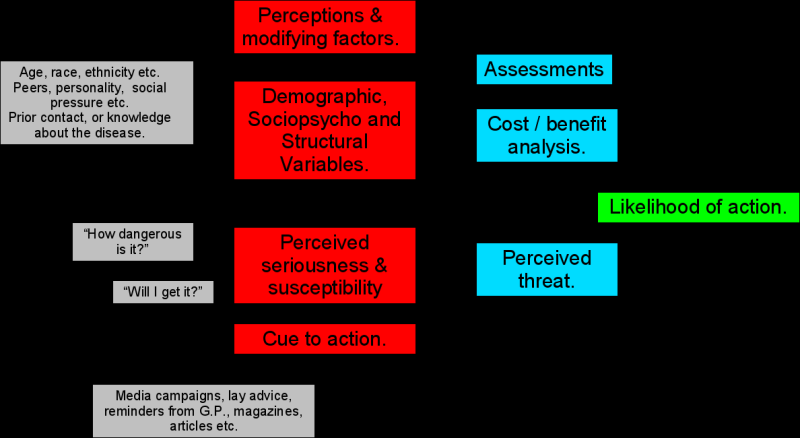

The health belief model was authored by Irwin Rosenstock in 1966. It consists of five factors, which are perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers and ability (See Appendix 1). In its role to explain and predict health behaviours, the model looks at the attitudes and beliefs of people in relation to their health behaviours aimed at introducing interventions (Glanz et al., 2008). This theory attempts to explain a change in health behaviour in relation to the thought processes behind the decision making of an individual. This model is helpful in determining the behaviour of the society towards a health issue. If an individual combines all the components of the model, they can take a preferred path. However, there should be a trigger that acts as a stimulus, for example, for a person to get sicker. The trigger is usually meant to make a person act (Glanz et al., 2008). The theory is easy to assimilate, and its predictions are testable (Rosenstock, 1966). The theory has been applied in three broad areas which are preventive health behaviours, such as vaccination and health promotion, sick role behaviour, and clinic use by patients for different reasons. According to the theory, behaviour is determined by the beliefs of a person about a disease and how its occurrence can be reduced through available strategies (Glanz et al., 2008). This theory is thus applied to scenarios involving disease occurrences. The theory mostly emphasizes on the costs and benefits of health behaviours and overlooks the personal and social factors (Rosenstock, 1966). This model uses the framework of common sense that simplifies representational processes related to health.

Limitations to the Health Belief Model with Regard to the TRA

A comparative analysis of the Health Belief Model and the Theory of Reasoned Action share a number of similarities. In particular both theirs base their assumptions on the a person should have an incentive to trigger decision making (Janz and Becker, 1984). In addition, both models disclose individual’s evaluation of positive and negative consequences of a particular behaviour. Despite the identified commonalities, certain different exist between the theories. In particular, the Health Belief Model perceives and identified social barriers, namely common beliefs that prevent patients from taking decisions (Janz and Becker, 1984). In contrast, the TRA amplified the importance of social context (subjective norms) for fostering the decision making process. Overall, though the TRA is conceptually identical to the HBM, it still provides the construct of behavioural intention being the core of changing behaviour. To enlarge on this issue, the TRA is more focused on the importance of personal intention for defining whether a particular behaviour will occur. Normative beliefs, therefore, play a pivotal role in the TRA that consider what a person believes other individuals would expect his/her to do.

Justification for the TRA for this study

The TRA is useful in determining the knowledge, attitude and beliefs of oncology nurses regarding pain management due to its strong predictive utility in predicting activities and situations with an assumption that behaviours are volitionally controlled. The theory correlates attitude and volitional behaviour more strongly than any other theory (Fishbein, 2008). Furthermore, this theory has been widely used in social and psychological studies to examine behaviour (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Fishbein, 2008; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Sasane, 2008). Unlike the Health Belief Model, the TRA incorporates social factors to facilitate the establishment of how subjective norms influence behaviour, thereby placing oncology nurses differently in managing pain (Mark, Suprasert & Grandjean, 1995: Ajzen, 1991). The TRA predicts behavioural intentions, attitudes and behaviour. Moreover, the theory explains the limiting factor on attitudinal influence through the separation between behaviour and behavioural intentions (Sasane, 2008).

The TRA will be the method used in this study both in the collection and in analysis of both the qualitative and quantitative data. The different variables will be quantitatively correlated to find the association between behavioural intention and behaviour with attitude towards behaviour and subjective norms. The study will demonstrate whether attitude affects the behaviour of oncology nurses in managing patient pain. It will further find out whether the relationship is determined by intention. The TRA has been successful, because it accommodates normative influences.

References

Ajzen, I. & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Armitage, J. & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: a meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–99.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Belleau, B. D., Summers, T. A., Xu, Y., & Pinel, R. (2007). Theory of Reasoned Action: Purchase Intention of Young Consumers. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 25, 244-57

Eagly, A., & Chaiken, S. (1995). Attitude strength, attitude structure and resistance to change. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fishbein, M. (2008). Medical Decision Making: A Reasoned Action Approach to Health Promotion. Web.

Glanz, K., Rimer, B. & Viswanath, K. (2008). Health behavior and health education Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Godin, G. & Kok, G. (1996). The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion, 11, 87–98.

Janz, K. and Becker, H. (1984). The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Education & Behavior, 11(1), 1-47

Madden, J., Ellen, S. and Ajzen, I. (1992). A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 3-9

Miller, K. (2005). Communications theories: perspectives, processes, and contexts. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rosenstock, M. (1966). Why people use health services. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 44 (3), 94–127

Sasane, M. (2008). Assessment of Attitudes and Norms about HIV Testing Among College Students In India Using Theory of Reasoned Action. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, n/a

Sheppard, B., Hartwick, J. & Warshaw, P. (1988). The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 325–343.

Vanlandingham, M.J., Suprasert, S., Grandjean, N., & Sittitrai, W. (1995). Two Views of Risky Sexual Practices among Northern Thai Males: The Health Belief Modeland the Theory of Reasoned Action. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(2), 195-212

Appendix 1