Introduction

Marketing is the most powerful weapon available to a business; however, marketing is often confused with sales and advertising. It is noted that businesses need to understand that marketing is much more than that. Marketing, in fact, has a many roles in a firm or business; firstly, it connects the business with its target market, it provides the major link between the business and its customers. Secondly, as marketing focuses on the needs and wants of customers, it gives a business direction and helps it to manage in a changing environment. Thirdly, it provides the knowledge of the business requirements as to change tracks or regulate its tactics by giving new goods or changing active goods. Fourthly, marketing helps to coordinate how a business can best use its resources to satisfy customers and achieve profit targets, yet the marketing plan can actually be seen as the ‘blueprint’ for a business’s future success. As it is noted in order to take out the marketing program, a business wants a method that will assist it to get its targets, and there are many steps needed to be taken; which include the situation analysis, establishing market objectives, identifying target markets, developing marketing strategies, preparing a marketing plan, and the implementation, monitoring and adjustment of the plan. (Abou-Ismail, 13-19)

Situation analysis involves looking at the market in terms of size and growth, needs of the target market and trends in buyer behavior, where the performance of the product(s) in terms of sales, profit margins and stage in the product lifecycle are examined, and major competitors are identified. The next stage in the marketing plan is about establishing marketing objectives; the objectives established in the business plan will be the guide for the marketing objectives. A number of general marketing objectives can be identified, such as, increasing a business’s market share, developing new goods or services, expanding the existing market, and entering new markets, etc. Moreover, identifying target markets involves breaking down the market into smaller segments or parts; this process is called market segmentation. Once the whole market is broken down, a business can then decide which target group of customers it will focus on. After identifying the target market, a business’s management department has to develop the marketing strategies that will allow the business to satisfy the wants of the targeted market and achieve its marketing objectives. It is noted that the marketing mix makes up the core of business’s marketing strategies, there are totally four elements of the marketing mix included in the marketing mix; the product or service offered for sale, the price structure, the promotional activities, and the distribution network of the business. (Abou-Ismail, 13-19)

Whilst many results in CO research are too great degree deviates, mainly support the idea that CO information can prejudice customers’ product preferences and behaviours toward many marketing mix elements. The present literature on CO has given precious knowledge about how customers in many countries observe foreign goods. By and large, all global organisations in order to establish victorious marketing plan in international markets depend on CO.

Though, experiential work on CO effects in recently flashed up or rising global markets is limited in spite of the rising number of multinational firms increasing into these markets, hence the need to healthier understand customer perceptions in these markets is burly.

Finally, since consumer behaviour toward CO and information marketing mix have changed with the passage of time, the requirement of continuous evaluate consumers’ behaviour in many international markets is justified. In this regard, this research tries to evaluate consumers’ behaviour towards a set of marketing mix rudiments linked with international goods in Qatar.

The marketing mix rudiments are examined for goods of Qatar’s main trading partners, namely, the U.S., Japan, Germany, Italy, the U.K., and France. (Aamer and Ibrahim, 12-37)

In this regard, Qatar has been observed as a good nation for this research. Firstly, with a Gross Domestic Products close to three billions of US dollars, every year, export of Qatar goods to international market raises every year by approximately 2.5 US dollars. Moreover, Qatar market is considered as one of the big player in international business as compare to others developing countries. For instance, Bangladesh has Gross Domestic Products of four billion of US dollars per annum; however, it has approximately hundred millions populations which seem not good to strike international market.

As a thriving customer market, Qatar is suffused with innumerable numbers of overseas brands covering each imaginable product group. Second, overseas competitors have been vying for a piece of the Qatari market whilst using

With countries such as United Arab Emirates, Oman, Bahrain, and other GCC countries, logistically viewing, Qatar seems as a foundation for achievement of international market goods demand. Interestingly, most of the Qatar’s population have adopted the Western traditions. Hence, consumers of Qatar have a great knowledge about domestic and international commodities.

This homogeneity has led to a general idea of inheritance, cultural harmony, and customer preference among the citizens of Qatar and other GCC states. As a result, a sympathetic of Qatari customers’ behaviours toward foreign goods might also shed some light on customer recommendations of other GCC states which stand for tremendously striking global markets. Lastly, an investigation of imported goods from the U.S., Japan, Germany, Italy, the U.K., and France reveals that there subsist strong similarities between the types of customer goods imported from the aforesaid countries. In addition, a high proportion of goods, consumed in Qatar, is imported from these six countries. Per se, it can be likely that customer prejudice because of variations in product types and ethnocentric prejudice will be negligible. Peters and Waterman quoted Young who made it clear that for “too many companies, the customer has become a bloody nuisance whose unpredictable behaviour damages carefully made strategic plans, whose activities mess up computer operations, and who stubbornly insists that purchased goods should work”. If this is the case in the United States’ domestic market, one would expect even greater difficulties in serving the Gulf market given the language, cultural, social, technological, and economic differences which distinguish the region and need to be accounted for in drawing up effective marketing plans. (Abou-Ismail, 41-55)

In developing such marketing plans those wishing to exploit the potential of the Gulf market will undoubtedly wish to draw on their experience as reflected in normative models of organizational marketing behaviour. However, these models are essentially based on Western experience in the United States and Europe. Their application elsewhere has been limited and a major objective of this article is to examine their utility and application in marketing to the Middle East and, particularly, the Gulf States. In general, the Gulf market has been considered only as a supplier of oil and not as a buyer of nearly all types of goods and services. Therefore, the strategic government, organizational, and political variables which influence the supply of oil have been emphasized, but the domestic demand of this market and its workings have received comparatively little attention.

A review of the literature on customer and organizational marketing behaviour reveals that little or no reference has been made to the factors which might distinguish the Middle East and Gulf markets from those of the West. For example, Engel et al. contains merely the subsequent paragraph: “cultural understanding is principally needed in developing countries as pictures might be a great deal more significant than words as an instance, one marketer tried to export his firm’s detergent to a Middle- Eastern country. Advertising for the detergent featured unclean clothes piled on the left and clean clothes stacked on the right. Reading right to left, as customers in the Middle-East often do, the meaning was obvious: soap soiled the clothes. Indeed, for most American and European businessmen it is true to say that their knowledge of this market is superficial. (Klenosky et.al, 189-98)

Literature Review

Socio-Cultural Environments

It has been concluded that members of a marketing group are mostly an expression of their mass socio-cultural domain. This might explain why Webster and Wind (1972) noted that environmental influences such as economic, political, legal, and cultural factors and the institutional groups which exert these influences “will vary significantly from one country to another, and such differences are critical to the planning of multinational marketing strategies”. A brief analysis of the socio-cultural variables and how they differ in the Gulf markets compared to the United States and Europe is presented below.

Tribal behaviour is still a dominant phenomenon in the Gulf even after the intensive urbanization which has taken place since the increase in oil income. This social variable is continuously influencing a person’s orientation towards other people, jobs, consumption patterns, etc. Hence, it is clear that a Gulf citizen has a deep orientation towards group welfare and prosperity rather than an individualistic orientation which represents the pattern of behaviour in the United States and Europe. In the Gulf extended/semi-extended families where the father and his married sons live in one house, sharing food and having supporting values towards each other has been found in 41 % of total families in Qatar.

In a community like this any person will be debased culturally if he neglects social norms and behaviour. Whilst there are several government organizations which control and audit managerial decisions, and many decision makers are keen to be objective in evaluating alternative offers, personal influence still has a major role to play in determining who will get the order. It follows that if one can appoint marketing agents from well connected Gulf families this will significantly enhance one’s selling efforts and chance of success. (Chao & Rajendran, 22-39)

Exporters wishing to develop Gulf markets must also be sensitive to gender issues. The number of women in the Gulf labour force is very low (9.4 % ‘ in Bahrain, 11.6 % in Qatar, 2.9 % in Qatar, 6.0 % in Saudi Arabia and 3.4 % in the Emirates and very few of these are in marketing positions. But, when the buyer is female, cultural constraints strongly favour female sellers. If this is not possible and a salesman is to be used then it is important that he does not raise the tone of his voice as this is regarded as a sign of disrespect. Similarly, extended eye-contact and handshaking are taboo from both a religious and social viewpoint.

When both seller and buyer are male one should not talk to decision makers who are old or have a higher status on a company’s organization chart, whilst exposing the sole of one’s shoe or toe directed to him. (It seems that this convention also applies in Japan and China. The buyer’s rank must be respected during the meeting or when writing to him. If the salesman forgets the official title of the buyer, this is taken as a sign of disrespect. If a salesman has established a good relationship with the buyer over a period of time, then instead of calling him by his official title, he could replace it with the name of his oldest son, preceded by “father of…” This implies that the salesman is dealing with the buyer as a friend. However, this approach is applied only when there is a very close relationship between the two people, otherwise it can create a very negative impression. (Chao & Rajendran, 22-39)

Organizational Marketing Models

A brief review of models of organizational marketing behaviour is presented here. The simple models have emphasized only one or two dimensions of how a firm as a decision-making unit moves from the non-buyer to the buyer group. Economists have considered that the organizational buyer is rational to the degree that economic variables alone such as price and cost items are the determinants of his behaviour. In contrast, behavioural models have emphasized the “irrational” elements of buyer behaviour such as ego enhancement, risk avoidance, satisfaction from dyadic relationships among sellers and buyers, and the orientation of each member of the decision group towards other members. Recently, several models have incorporated economic, social, psychological, and cultural dimensions in a single comprehensive model. Among the best known models in this group are those which were developed by Abou-Ismail, Baker, Howard, Howard and Sheth, Ozanne and Churchill, Peters and Venkatesan, Webster and Wind. Space limitations preclude an explanation of all of these models.

However, it might be useful to describe briefly Webster and Wind’s model, as it is representative of these widely accepted normative models. Four major criteria of organizational marketing behaviour have been incorporated in Webster and Wind’s model. These are: the behaviour of the marketing group; the environmental determinants (economic, physical, legal, etc); the organizational factors (goals, structure, technology, and actors); interaction and communicability. Some factors have a direct impact on marketing tasks, whilst others are non-task variables.

In this study we consider the role of economic, organizational and socio-cultural determinants of marketing decisions in the Gulf market and will seek to show how they suggest different outcomes from those to be found in Western markets. Our analysis is based on direct experience of both marketing and selling organizations in the Gulf for almost a decade and the academic research of one of the authors over this period. Most extant research on this market has been undertaken in Arabic and so is not readily available to non-speakers of this language. It has been used extensively in developing our analysis. (A1-Ateyah, 26-29)

Economic Dimensions of Gulf Market

The Gulf market is composed of six nations which are geographically connected but politically independent. These nations are Saudi Arabia, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Oman, Bahrain, and Qatar. Culturally, economically, technologically, and anthropologically these nations are similar. They are linked through an organizational body which was established in Riyadh in 1981 called the Co-operation Council of the Arab States in the Gulf. Table I summarizes some of the variables which might be useful to organizational marketers. Prospective sellers in the Gulf market must be sensitive to the possibility of market swings in organizational purchasing depending on the prevailing oil revenues. The dominant role of oil in the social, political and cultural life of the Gulf has been analysed in several research works.

Economically, statistics for the 1980s and the first two years of the 1990s (GCC Economic Bulletin) suggest that oil revenues represent 87.1 % of the total venues of Qatar, 80.8 % of those of Oman, 57.1 % of those of Saudi Arabia, 56.5 % of those of Bahrain, and 90 % for Qatar. Moreover, oil exports during that period ranged from 87 % to 95 % of the total exports of the Gulf according to World Bank statistics. When oil income moves up, economic prosperity rises with it in both customer and organizational markets. For example, E1-Koli connected the big jump in oil revenues directly after the 1973 war until the early years of the 1980s, with government expenditure.

He concluded that the Saudi market alone spent 69.7 billion dollars on infrastructure projects in the two years from 1977-79. The Saudi army purchased military equipment and weapons worth 34 billion dollars during the period 1971-1980. Moving to the 1980s up to 1991, it has been calculated that the six Gulf nations spent 114.8 billion dollars on purchasing military equipment and weapons alone. This consumes one-third of the gross domestic product of the Gulf nations. (Chao & Rajendran, 22-39)

As for non-military imported commodities, these are shown in Table II, together with total exports and market share of the three major competitors, Europe, Japan and the United States. As Table II suggests, the EEC group takes the lead concerning the exports to Gulf markets, Japan is the challenger, whilst the United States follows both. It is clear also that the incremental gains in export share to this market by American goods are taken from Japanese exporters and not from European ones, especially from 1988 on. This indicates that the competition is much fiercer between the challenger and the follower than it is with Europe, who is the market share leader.

Another observation which might not be immediately apparent to global marketers is that in the Gulf market one cannot separate foreign trade, especially military and governmental purchasing, from the political power of a given foreign country in the area. Europe with its long political and economic history in the Gulf is able to defend its market share better than Japan and the United States, although the latter are working hard to raise their share through the application of efficient marketing strategies (this applies to Japan) or on political gains in the area especially after the Gulf War (this applies to American firms). (Abou-Ismail, 41-55)

The history of the Gulf provides insight into the links between both political and economic gains. Prior to 1906 Gulf nations, together with Iraq and Iran, had been monopolized commercially by Great Britain. By 1906 Germany had established a new company called America-Hamburg Co for handling exports, imports and shipping activities in the Gulf. This, in turn, created competition between the two countries. Taking sugar as an example, in 1908 British firms exported to Iran 2,925 tons whilst the German firms achieved 1,950 tons, with a share of 60 % to the former and 40 % to the latter. But in 1913, after the success of the America-Hamburg Co, Germany exported to Iran 4,550 tons of sugar, leaving 650 tons only to Britain, with a share of 86.5 % for the former and 12.5 % for the latter. By 1929 the united States were in competition with Britain and Germany when it established oil companies in the I Gulf. Japan did not come on the list of nations which were competing in the Gulf at that time. In 1913-1914 Russia had a 60 % share but this shrank to 18 % in 1923-24. The United States had 1 % in 1913-1914, which increased to 4 % in 1923-1924. Egypt maintained a 4 % share over the whole period. (Dunkley, 16-18)

More recently the most noteworthy feature has been the success of Japanese firms in trading with the Gulf. Japan started to direct its attention to the area mainly after 1960. Hence, to be able to achieve nearly 23 % of the total exports compared with Europe and the US, which have a longer economic and political history in the area than Japan, could be considered as a great success and is largely attributable to the fact that Japanese companies are seen as being highly marketing oriented.

In other words, they are very close to their customers, carefully study their needs and desires, develop a specific marketing strategy for each market segment, and receive marketing research, R&D and communication support from several government offices. Exporting is central to the orientation of Japanese companies and is regarded as a matter of survival. Japan has to import almost all of its raw materials. It adds value to them through the manufacturing process and exports finished goods to maintain its trade balance. Although Schlender recognized that Japan is currently in a recession, he concluded that it is able to deal with this challenging environment successfully and will recover quickly. (Abou-Ismail, 13-19)

No one could write on the Gulf and neglect the implication of the Gulf war on the shift in political power and, thereby, trade power which took place after this war. In brief, and based on what has been written in Arabic and addressed in formal seminars, it is possible to conclude that the American firms are keen to translate the military victory into economic gains. The first sign came from Qatar at the beginning of 1993. It announced that the American firms had obtained the “lion’s share” of the after-war infrastructure projects.

Within a year American firms entered contracts with the Qatari government for the reconstruction and rebuilding of several projects equal to five billion dollars, with a share of 52.6 % of the total budget of these infrastructure projects during 1992. In her report to the Congress A1-Iktisad Walmal the Minister of Trade said in October 1992 that exports to the Gulf during the first nine months of 1992 had achieved 12.7 billion dollars against 6.4 billion during the same period before the Gulf War in 1989. That is to say, the American firms were able to double their reports to the Gulf within less than three years. The last estimate was confirmed during a formal meeting of groups of businessmen, both from the Gulf and the United States, which was held in Washington DC on 20 April 1993. (Darling & Wood, 427-50)

Organizational Environment and Marketing Decisions

The effect of organizational influences on marketing decisions has been confirmed I in numerous studies. The traditional view has emphasized the degree of participation of the purchasing department compared with other functional areas (i.e. production, finance, etc). This, in turn, has led to the analysis of a number of issues, such as: the status of this department within the organization; its degree of participation in and influence on the company’s decision-making processes; its perception of its role and its efficient and effective performance of it; top management’s view of this role; the professional and educational qualifications of persons working in it; the conflicts with other departments and how these may be solved. (Chao & Rajendran 22-39)

Background and Hypotheses

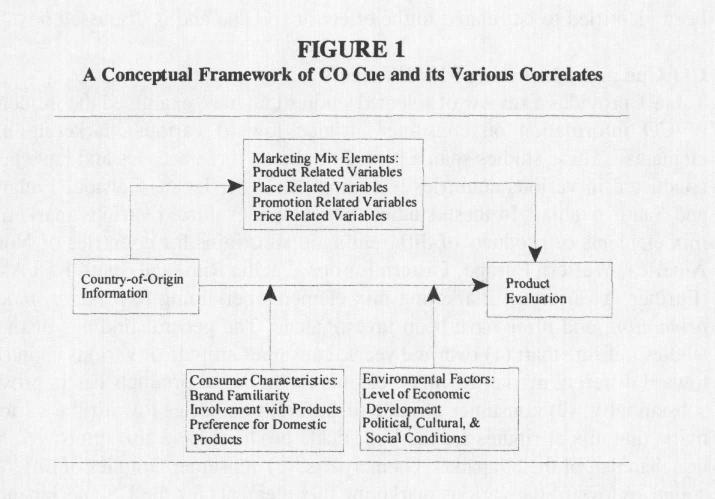

From last three decades, scholars have been researching customer evaluations of goods based on CO cue. Many studies have given extensive reviews of the literature on the result of CO information as others have examined the consequence of CO information, holding other issues the same.

Almost all the researchers have evaluated the control of CO cue on elements, which can be categorized into three categories. Firstly, consumers of Qatar always effected of CO information on product assessment. For example, a high level of brand conversance of unlike domestic origin is considered to be linked to modicum uses of CO information and vice versa. Furthermore, Hugstad and Durr believe that consumers of Qatar often require CO information of high-engagement goods which is not the case in low-engagement goods.

Few studies have found that customer fondness for home goods can control the effect of CO information. Second, a set of outside ecological aspects has been concurrent with the influence of CO cue. Particularly, customers classically view foreign goods of developed countries added positively than those of less developed countries. “It has also been examined that the political, cultural and societal conditions of nations can manipulate the figure of such nations and as a result how goods of these nations are evaluated. At last, a set of marketing mix elements, the centre of this study, has been identified to be related to the consequence of CO cue and is discussed next”. (Ettenson et.al, 127-33)

CO Cue and Marketing Mix Elements

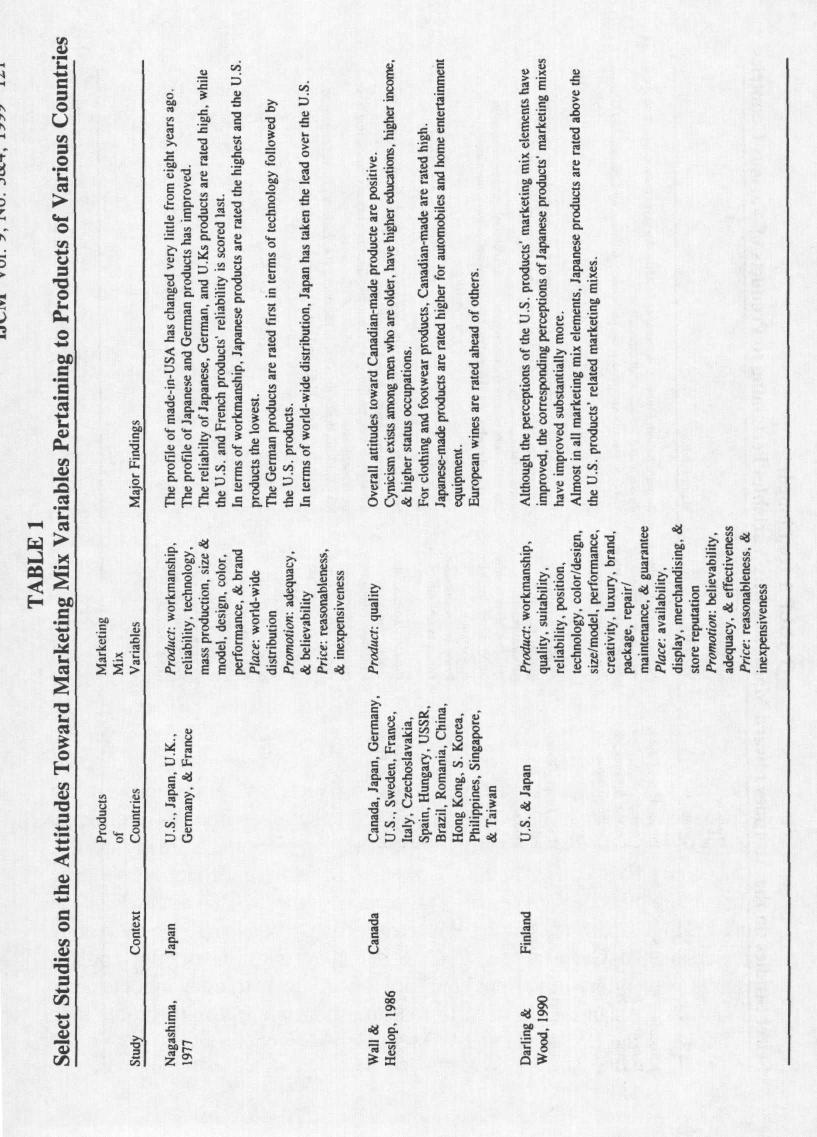

Table 1 shows a summary of selected research that has been evaluated by the effects of CO information on consumers’ behaviour towards marketing mix components.

These studies span a era of approximately three decades and have been conducted in many countries with the U.S., Japan, Canada, Finland, and Saudi Arabia. In these studies, many components of marketing mix of diverse goods have been examined by the consumers for nations such as Eastern and Western Europe South-East-Asia and Pacific Rim. Furthermore, different forms of marketing mix components pertaining to product’s price, endorsement and place have also been examined in these studies.

The common findings of these studies point out that: (1) over the years, customer behaviour of many countries toward diverse marketing mix elements for Japanese goods has improved considerably; (2) Consumers’ behaviour of different nations towards the marketing mix attributes for the United States goods have also increased as compare to Japanese counterparts. (3) Constant convergence trend has also been seen in consumers’ behaviour of diverse nations towards marketing mix components especially in the US. (4) Consumers of various nations observe the marketing mix cues of Western European nations less positive as compare to the United States and in some Japanese counterparts. (5) amongst Western European countries, the marketing mix rudiments of German goods are apparent most positively; and (6) By and large, consumer’s awareness of different nations toward the marketing mix components of the South-East-European goods are positive as compare to Japan, United States and in some European nations.

Goods of France, Italy, United States of America and Germany goods have greatly linked with Qatar’s consumer behaviour towards marketing mix components.

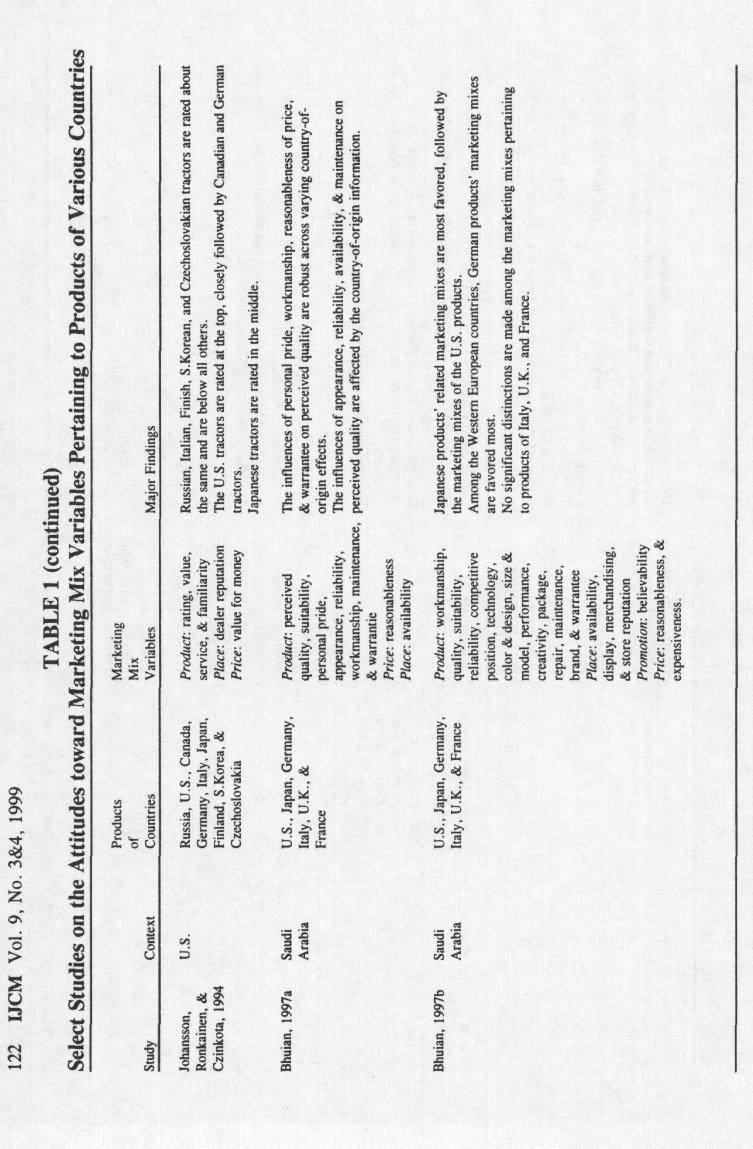

Figure 2 summarizes the hypothesized associations of Qatari customer behaviours toward thirteen marketing mix elements of goods of the U.S.A., Japan, Germany, Italy, the U.K., and France. “Out of the 13 marketing mix elements, 5 relate to goods (package design and number of sizes, wrap up labels and use precautions, brand reconcilability and information ability, repair and maintenance services, and warranties and guaranties), 3 are related to place (retail accessibility, sell display and merchandising, and retail character), two are apprehensive with price (price fairness and inexpensiveness), and three are related to endorsement (believability and reliability of advertisements, adequacy of advertisement, and quality of advertisement and advertisements). The assortment of these thirteen marketing mix elements was guided by the results of past studies and their significance and relevance to Qatari customers. As a fairly detailed dialogue of the hypothesized relationships is given by Bhuian in a same framework, merely a concise synthesis is offered in order to preserve space for discussing the experiential aspects of thestudy in detail”. (A1-Ateyah, 26-29)

“The hypotheses are grounded on the principle that the more the Qatari customers have positive perception about a CO, in terms of the country’s business firms’ understanding towards Arabic customs and Islamic values, the more positive would be the ideas about the marketing mix elements connected with goods of the state. Past study point out that business firms of the six countries included in this study are in discrepancy in terms of their progression towards adapting their individual marketing mixes associated with their goods in the Gulf, including Qatar. Customers in the Gulf states, in broad, have a lot of separate preferences influenced by Arabic customs and Islamic values, for example the colour green is valued as holy and black as demonic; any public display of bodily expressions is highly disliked; standard family size is large; literacy rate is less than 50 %”; the media infrastructure and convenience to the media is imperfect; the climate is awfully hot and dry; the water contains high minerals and salt; a strong faith in fatalism prevails amongst the customers; the retail infrastructure is mainly small stores; and the customers have a long custom of haggling. (Ettenson et al, 127-33)

“A little studies in the region account that customers in the Gulf states take side to the U.S. and Japanese goods and their associated marketing mix elements the most, followed by that of Germany, whilst that of Italy/UK/France together dwell in the third place”. The earlier way of thinking has led to advancing the subsequent hypotheses: (Ettenson et.al, 127-33)

- H1: “Qatari customers observe the package plan and number of sizes, the package labels and instructions, the brand reconcilability and information aptitude, and the repair and maintenance for goods of Japan and the US most positively, followed by the goods of Germany. These features are least preferred for goods of Italy, the UK, and France.

- H2: Qatari customers observe the warranties and guarantees for goods of Japan, the US, Germany, Italy, the UK, and France to be the identical”. (Aamer, and Ibrahim, 12-37)

- H3: Qatari customers observe the retail accessibility for goods of Japan and the US most positively, followed by the goods of Germany, Italy, the U.K., and France.

- H4: Qatari customers observe the retail exhibit and merchandising and the retail character for goods of Japan and the US mainly positive, followed by the goods of Germany. These features are least preferred for goods of Italy, the UK, and France.

- H5: Qatari customers observe the price sensibleness for the goods of Japan and the US most positively, followed by the goods of Germany this characteristic is slightest preferred for goods of Italy, the UK, and France.

- H6: “Qatari customers observe the price inexpensiveness for goods of Japan mainly constructive, followed by the goods of the US and Italy. This quality is least preferred for goods of Germany, the UK, and France”. (Aamer, and Ibrahim, 12-37)

- H7: Qatari customers observe the believability and dependability of advertisements, the sufficiency of advertisements, the excellence of advertisement and advertising for goods of Japan and the US mainly positive, followed by the goods of Germany. “These characteristics are least preferred for goods of Italy, the UK, and France”. (Aamer, and Ibrahim, 12-37)

Methodology

Data Collection

“The information for this research was collected from Qatari customers. At first, a hypercritical sample from together public and private institutions was chosen. Public institutions incorporated educational institutions, metropolis offices, hospitals, and city management offices, whilst private organizations such as of banks, retail stores, wholesale houses, and tiny industrialized facilities. These varied institutions were selected to augment sample representativeness of the inhabitants. Consequently, a random taster of employees, staffs, faculty, and students from the selected institutions was individually approached and asked to contribute in the research. A total of 200 questionnaires were dispersed. After three call-backs, 113 questionnaires were retrieved.

Out of these 106 questionnaires, 19 were inoperative and had to be dropped at the editing stage. The return rate was 49 % which compares positively with other studies in the area. The expediency example approach used in this study was not enough but was essential. Such as, an official list of inhabitants that could dish up as the sampling frame did not exist. In addition, the societal traditions in Qatar prohibited access to Qatari households or conducting personal interviews with Qatari women. The description of the respondents identified that the mainstream, 52%, was between 35 to 54 years old followed by 40 % between 18 to 34 years; 70.3 % had some college qualification or a university degree, 80.8 % had a family of 3 to 10 people, nearly 50 % had earned the equivalent of USD 25,000 per year, and an overwhelming 83.8 % was male. On the whole, the profiles of the respondents expressed that they were younger, extremely educated, had large families, and high incomes. This outline intimately resembled the middle class of Qatar who have strapping interests in a lot of customer goods of diverse countries. Furthermore, as education was not as widespread as in developed countries, these responses may look like the behaviours of the opinion leaders”. (Tosi, and Carroll, 1617-28)

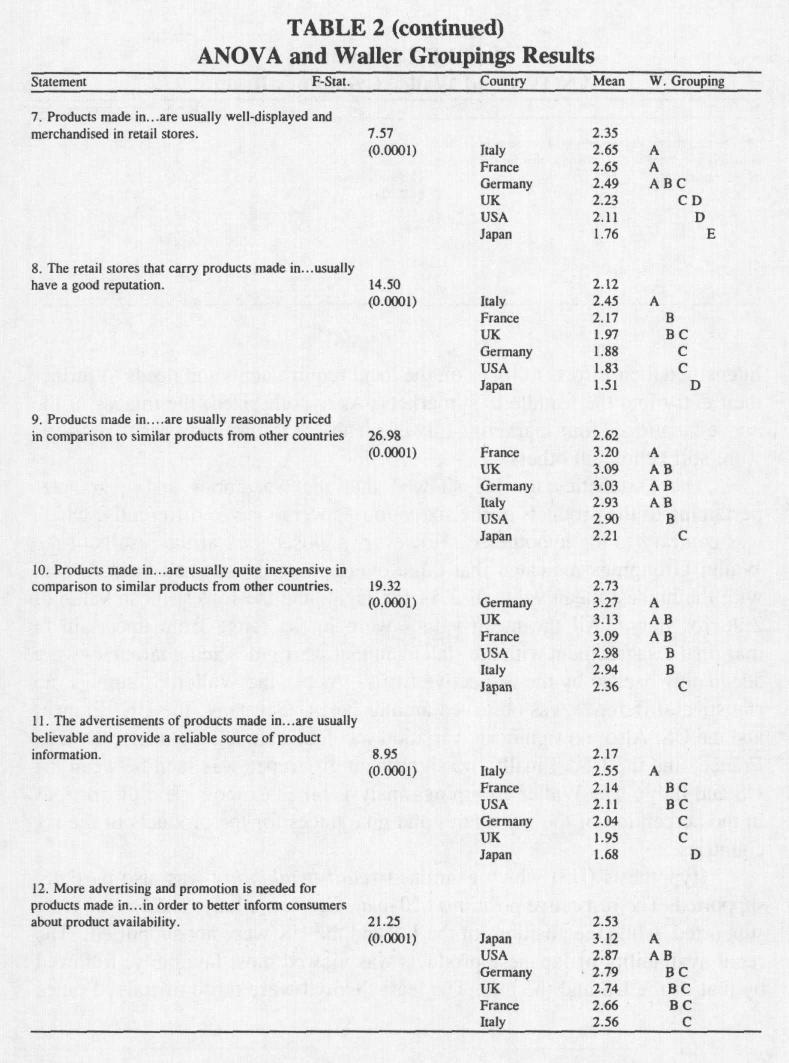

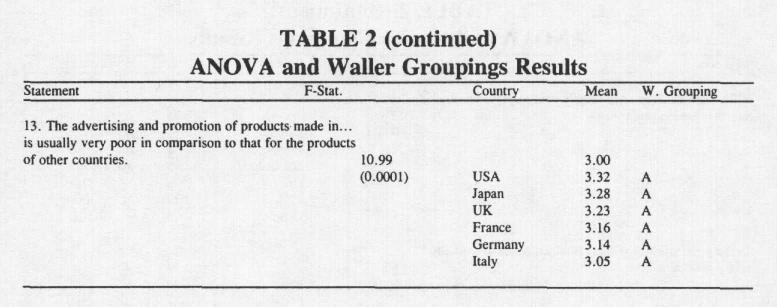

Qatari customer behaviours toward thirteen marketing mix elements for goods of the USA, Japan, Germany, Italy, the UK, and France were calculated on thirteen single-item scales strained from preceding study. All the scales represented Likert-type statements. For every scale, respondents were asked to answer along a five-point scale ranging from 1=strongly agree to 5=strongly differ. The scale statements could be seen in Table 2. Two versions of the questionnaire were used. One was the unique English version and another one was a translated Arabic edition. For the latter Arabic edition, the back translation procedure was used to make sure that the questions were correctly translated into Arabic. In investigating the study hypotheses, the examination of discrepancy and Waller-Duncan k-ratio t-test was used. Both of these patterns were performed for every of the thirteen items to settle on if the CO information were linked to the variations in the perceptions of 13 marketing mix elements for the goods of the six countries. (Yaprak, & Baughn, 263-69)

Results and Discussions

Table 2 presents a synopsis of our analysis. “The results identified that HI, which was related to the package design and number of sizes, package labels and use direction, brand reconcilability and knowledgeability, and repair and maintenance services, was partly supported. These 4 marketing mix rudiments for Japanese goods were mainly preferred by Qatari customers, followed intimately by the US, the UK, and German goods”. These characteristics were slightest preferred for French and Italian goods. A clear lead by Japanese goods on the above 4 characteristics showed to be reliable with the results of a earlier study in Finland. In a same study involving Saudi Arabian customers, the perceptions of these 4 characteristics of Japanese and the US goods converged. (Cordell, 251-69)

“Though, a small dissimilarity between these two countries yet remained in the Qatari market. Amongst the Western European nations, Germany and the UK trapped up with the US in the Qatari market. This development of Germany and the UK in the Qatari market could be explained by a current report in the Saudi Commerce & Economic Review which showed that German and UK firms intensified their efforts to focal point on the local needs and to more their entrance into the Middle East markets. As hypothesized, the descriptions of the above mentioned 4marketing mix elements for Italian and French goods were yet behind all others”. (Cordell 251-69)

Marketing Tasks

The marketing task has been defined by Levitt in terms of “organized work” which is done and aimed at “achieving specific objectives”. Task structure refers to the degree of clarification and definition which is required. Again, the traditional view of marketing tasks has tended to concentrate on the functions of the purchasing department compared with other departments. This department’s fundamental tasks are: sourcing suitable manufacturers; sourcing suitable product quality at an acceptable price; achieving satisfactory economies of scale; and all at the appropriate time. Marketing models have defined marketing tasks in terms of stages through which buyers are informed and motivated to select a particular brand. The most commonly cited stages are: needs identification; description of requirements; search for potential alternatives; evaluation of alternatives; and selection of brand and supplier. In the case of organizational marketing behaviour the usual emphasis has been on marketing as an input to manufacturing rather than for resale. In the Gulf market the opposite is the case.

The share of the industrial sector in gross domestic product of non-oil sectors amounted to only 9.1 % in the Gulf in 1990. Whilst it is anticipated that industrial investment by Gulf Nations will increase in the 1990s, it is clear that it has a long way to go to catch up with purchases for resale. Some indication of the growth in industrial development is provided in Table III which records a significant increase for the period 1975-1990. However, compared with Egypt, for example, the Gulf nations do not have a strong, supportive orientation towards industry. This might be as a result of the constraints related to know-how, or to the availability of other less risky but more profitable investment proposals such as retailing, tourism, imports and exports, etc. (Abou-Ismail, 41-55)

Marketing Group Composition and Behaviour

Marketing group membership, roles, and interaction have been analysed in numerous studies. The role of many departments has been discussed at length. These departments are purchasing, production and quality control. The number of participants in the marketing decision from these departments and other functional areas becomes greater in the following situations, as suggested by Sheth. (Al Hammad 15-17)

- When the product creates a high degree of ambiguity and risk.

- When the decision requires a large amount of invested capital and/or the pay-back period is relatively long.

- When the time pressure is not acute.

- In cases of large and decentralized organizations.

The composition of the marketing group in the Gulf market creates different problems from those which have been conceptualized from the experiences of American and other Western markets. One major problematic criterion is that the marketing group in government-controlled firms is composed of multinational participants, each with its own role perception, behaviours towards other nationalities, cultural orientations, educational background, etc. Although market segmentation might be a solution to this problem, the Gulf market still differs compared with what marketers understand from the experiences of other global markets. For example, in Saudi Arabia in 1990 51 % of the civil work force was non-Saudis although it is planned that this should reduce to around 35 % by 1995. In Qatar, the most recent census for 1990 estimates the non-Qatar labour force as 93.6 % whilst for the Qatari labour force as a whole Qatar is numbered only around 19 %. (Tosi, and Carroll, 1617-28)

Job tenure is not guaranteed for foreigners, which requires adaptation in building relationships between buyers and organizational sellers. Whilst it may be necessary to concentrate on foreign members of the marketing group to conclude specific or short-term transactions, long-term relationship building must be achieved with the Gulf members. As might be expected non-Gulf nationals are only appointed to positions of responsibility where they possess particular expertise. Even so their actual authority will vary considerably according to circumstances. Direct experience suggests that: The relative formal and informal roles and influential power of each non-Gulf member will fluctuate depending on his ability to use the non-task behavioural aspects for maximizing his views. Of particular importance is winning the support of “a decider” member of the marketing group. (Ettenson et.al, 127-33)

- Some members (especially among non-Gulf nationals) do not express their own views concerning alternative offers before making sure which offer is receiving the support of the most formally powerful member of the marketing group. These members are known as El-monafikon or flatterers.

- Some members follow a “withdrawal” strategy when Gulf members disagree with their ideas for personal rather than objective reasons. In this case they convince themselves that their role as foreigners is to suggest ideas, and not to “push” the Gulf’s decision makers to follow their views. “This is not our country but theirs” is a common slogan among non-Gulf workers.

- Final authority usually rests in the hands of a marketing member who is from a big family or a tribe even if he is not the formal head of the marketing group. The family’s political standing, roots, wealth, and size is a very important source for its members in gaining informal authority which will often exceed formal authority as defined in a job description manual.

- Because foreigners are rarely given a permanent job their membership of marketing groups changes over time. Clearly, the importance of informal versus formal authority and the influence of cultural aspects are significant issues when addressing marketing groups comprising different nationalities. The Gulf market presents a major example of these aspects and thus merits further research. (Abou-Ismail, 13-19)

Since the structure of the marketing group in terms of nationalities and departments which are involved in the process differs from one marketing organization to another, it is important to design the marketing intelligence system to provide up-to-date information on the structure of this group in each target organization. This requires the field salesman to spend effort in investigating and analysing the roles and influential power of each member of the marketing group to save his time and effort.

This process could start with Gulf members and their close partners from other nationalities whose job and/or expertise puts them among the initiators, influential, or possibly, in some cases, the gatekeepers of marketing decisions. The continuous interaction over time between a salesman and members of the marketing group is essential to gain a better understanding of behavioural and organizational variables which influence the response of each decision maker to particular marketing stimuli. To do this task efficiently, the salesman must have a good understanding of the cultural, behavioural, and social aspects of the Gulf market. Hence, the appointment of people of Gulf or other Arab nationalities to perform marketing jobs could work well in this environment.

Investors on the Doha Securities Market (DSM) had a good year in 2004; with the benchmark DSM index up by 65 % and volume, value and number of transactions all doubling, the year’s ahead promises to be equally exciting with many initial public offerings (IPOs) in the pipeline. And non-Qatari are set to share in the windfall, after the Council of Ministers approved in early January a proposal to allow foreigners to trade in DSM shares. On the immediate horizon, the major market event is the IPO of shares in Qatar Gas Transportation Company (Q-Gas), which went on sale on 16 January for one month, sucking a little liquidity from the exchange. On offer are 240 million shares priced at QR 10 ($2.70) each in the firm, which will own 57-75 liquefied natural gas (LNG) vessels. Qatar National Bank (QNB) is acting as lead manager, whilst Sumitomo-Mitsui Banking Corporation is advising on the purchase of the ships. Many more IPOs are planned before the end of the year. (Al Hammad, 15-17)

All stocks have been doing well recently, although there has been a slight correction in the past week or so, making valuations more sensible, banking stocks have done particularly well. Stocks in QNB, Doha Bank and Commercial Bank of Qatar (CBQ) are up strongly since the start of the year, and all eyes are now on the imminent release of 2004 results, which tend to appear rather later than elsewhere. Qatar Islamic Bank shares have also done well since the bank was awarded a licence to operate in Malaysia in late 2004 and its stock accounted for the greatest value traded in December. Banks occupied four out of the top five positions in terms of value traded, the interloper being Industries Qatar — a good example of the profits nationals are likely to accrue from the Q-Gas sale.

The opening of the market to foreigners should provide an injection of energy into the market, although the exact timing is not yet clear. Non-Qatari’s will be limited to ownership of 25 % of companies’ share capital. At present only a limited number of stocks are open to foreigners, including those of Qatar Telecom (Q-Tel) and Salam International Investment. Q-Tel’s share price be one to watch in 2005, as the success of its venture into the Omani market becomes clearer. The local market is set to receive a boost if the Qatar Financial Centre, launched by Economy & Commerce Minister Shaikh Mohamed al-Thani in early January, takes off as planned in the summer. As well as attracting commercial banking and project finance business, the centre dill also look to develop support services, likely to have a knock-on effect on the sophistication of the local bourse. On a macro level, the booming local economy should ensure that the DSM is among the best-performing regional markets for some time to come. (Yaprak, & Baughn, 263-69)

Bureaucracy and Marketing Decisions

Bureaucratic theory following the work of Max Weber has been discussed in numerous texts and models since its publication in Gerth and Mills. Research by the authors in the UK showed that bureaucratic organizations resisted innovations, whilst prolonging the time lapse to adoption in other groups. Abou-Ismail confirmed these findings in a study of Qatar industries. It is interesting to note that bureaucracy has its roots in the Gulf area and other parts of North Africa since the ancient Egyptians invented and applied rigid rules for controlling persons who were involved in trade with ancient nations such as Babylonia, China, Greece, India, and Persia. Recently, Egyptian employees in the Gulf have transferred their managerial systems to the Gulf States without giving- consideration to the differences in size, managerial environment, and social construct between their domestic market and that of the Gulf. (The bureaucratic rules and their effect on many economic and managerial developments in Egypt, including marketing, have been assessed in numerous studies. (Shimp & Sharma, 280-89)

The impact of this bureaucratic tradition is particularly noticeable in Government decision-making. For example, it took 13 years for McDonald’s to obtain permission to sign a franchising contract with a Saudi food distributor. The negotiations started as early as 1978 and continued until 1992. During the period from 1980-1986, Gulf governments exercised powerful roles in the economic life of their communities compared with the private sector. This, in turn, had implications for the nature and volume of organizational marketing. This powerful role of government is explained through their relatively higher expenditure rate compared with the private sector. During the period from 1980-1988 government expenditure was 47 % in the Emirates, 29.8 % in Bahrain, 45 % in Saudi Arabia, 46 % in Oman, 59 % in Qatar, and 31 % in Qatar (GCC Economic Bulletin, 1988). Moreover, the Qatar Chamber of Commerce gives figures confirming that the government firms’ share in the value added of Qatari industry was 72 % in 1987, whilst the private sector share was only 28 %. To rationalize marketing decisions for materials, supplies, equipment, machines, and services, Gulf governments have established many big central agencies for making government purchases. Moreover, a central organization has been established in Riyadh for marketing common governmental commodities such as school stationery. The trend towards more centralization in government purchasing has its effects on many dimensions of the marketing strategies of selling firms, e.g. product design, promotion, and pricing.

Moreover, the establishment of Gulf central agencies in marketing or other functional areas helps to create a power struggle between them and the parallel organizations in each Gulf nation. In addition, there is a Central Agency for accounting which controls government expenditure, thus further complicating the marketing decision process. In Qatar, for example, it took more than a year for a Qatari firm to define the needs of Doha Airport for two fire engines and to import them from England. (Bhuian, 217-34)

Marketing wisdom calls for patience in handling the time consuming procedures involved in dealing with this bureaucracy. Moreover, the sales function must be designed in light of these organizational constraints. For example, the salesman’s job would be much easier and much less time consuming if he had to hand a chart indicating the marketing authority centres inside and outside each firm, and the pattern of communication networks among the marketing group members. If the salesman draws on this chart he will soon discover that it differs in many ways from the authority centres shown on the formal organization chart of the firm. Informal authority in the Gulf market is quite different from the United States and Europe. It gives some decision makers greater influence over the outcome of the marketing decision and the successful salesman will be the one who is able to determine who these individuals are and develop the most efficient methods for dealing with their economic, social, and psychological motivations and desires.

Qatar Airways is the new sponsor of Sky News Weather The 12-month deal marks a first for Qatar Airways, which has never before used television as a promotional tool in the UK. It is part of a strategy’ to target the business and premium leisure market. Starcom Plus, the sponsorship arm of Starcom UK, negotiated the deal, which exposes the airline to a potential new audience of 21 million people through 20 bulletins per day.

Starcom handles planning and marketing for the airlines, Starcom Plus director Adam Bishop says: “The broadcast exposure and integrated nature of the sponsorship means that awareness of Qatar Airways will be significantly boosted in the UK,” The online element of the deal will enable Qatar Airways to stream interactive ads through Sky Active, allowing customers to go onto Sky Digital Text and get the best flight deals and prices, whilst also streaming ads through the live programming part of the news site. It was important to ensure the online look and feel was identical to the TV sponsorship, so the streaming of the bumper ads was used when people entered or exited the online weather reports too. he UAE’s impressive figures on advertising are a result of extremely aggressive marketing campaigns by telecommunication giants, real-estate developers and governments, according to Arab News. Fourth quarter spending was also boosted by national elections in the UAE as well as the launch of Du Telecom, both believed to have contributed a combined $326.7 million to advertising spending. The largest spender on advertising nation-wide in the UAE was Watania-UAE, a government entity responsible for carrying out national identity program.

Watania spent a whopping $14.5 million on television spots, which pushed Nokia from its former No. 1 position. In the Arab Mashreq, on the other hand, the largest market in terms of advertising expenditures was Egypt, with $754 million. Also notable in the Mashreq was the advertising market of Lebanon, which rose 21 % year on year during the first six months of 2006 and then plummeted 60 % in July and August as war broke out with its southern neighbour, Israel. Indeed, the summer war with Israel spared none of Lebanon’s more than 60 advertising agencies, whose clients cancelled pre-booked campaigns across all media once the violent conflict began, according to Ya Libnan. Despite the fighting and the drop in expenditures, Lebanon’s advertising market, characterized by its brashness, managed to put up its own fight.

In fact, only days after the war ended, the nation’s tourism sector flexed its advertising muscle with signs such as that at the Edde Sands beach resort which read: Come back… The war has finished. Advertising major Leo Burnett Middle East and North Africa later went ahead with plans to hold its annual planning meeting in Lebanon in November in a major show of support for Lebanon. Speaking on the strength of the Lebanese advertising industry, chairman and chief executive officer of Leo Burnett, Tom Bernardin, said that Beirut had “proven time and again to be a city for the ages and a city that breaks through the clutter by defying all challenges to create world-class advertising.

Time Pressures

Another dimension which is also related to bureaucracy is time perception. As one author notes for many Gulf managers, planning (including timing) involves dealing with the unknown – a domain which properly belongs to God, not man. The difference between Western and Eastern perceptions of time has been commented on elsewhere. The fact that Gulf decision makers have access to the latest ideas and technology for planning and decision-making has, so far, failed to alter the lack of importance attached to time aspects. Western sellers clearly need to allow for this in their own planning. (Yaprak, & Baughn, 263-69)

Images of Foreign Countries

An important factor influencing the exporters’ marketing strategy must be the image which his country, his company and his goods have in the eyes of the intended purchaser. This dimension becomes very important in global marketing when the customer asks about the country of origin before arriving at a decision. But, the customer does not generalize his positive or negative images to all product classes produced by the same country. He might put Japanese cars in a top position, but aircraft produced by it at the bottom in terms of reliability, long life, etc. In a survey of Qatari firms in 1982 Abu-Ismail examined the images of seven industrial nations on five major attributes. The findings are shown in Table IV. Since this study it is clear that Japanese goods have made considerable progress in Gulf markets and may well have moved into top position given their near 23 % share of the total market during the 1980s (GCC statistics).

More information and market research is called for especially as a more recent survey of 134 Qatari firms indicated considerable dissatisfaction with sellers of high technology goods who were seen as “unfair, greedy and neglecting the interests of Qatari buyers”. As noted earlier, history has had its effect in influencing trading patterns between Gulf nations and other countries and this is still apparent in country-of-origin effects. That said, in the final analysis marketing decisions are largely based on product performance and perceived value and it is this which has the major influence on country-of-origin perceptions. (Tosi, and Carroll, 1617-28)

External Environment

“Companies are operating within a larger framework of the external environment that shapes the opportunities and threat to an organization. The external environment for global and domestic marketing decisions is comprised of forces that are apart of a company’s marketing process but is external to the organization”. Revolutionary products create new product-markets. Competitors are always developing and copying new ideas and products, making existing products out of date more quickly than ever (Perreault & McCarthy, 2002, p. 3). “Those forces include the organization’s market, its producer’s suppliers and intermediaries. It would be necessary for companies to understand that the environmental conditions because the conditions interact with marketing strategy decisions. The external environmental has a huge impact on the determination of marketing decisions. Any successful company will scan the external environment that affects them so they would be able to respond profitably to the unmet needs and trends in targeted markets”. (Perreault & McCarthy, 3)

Variables

There are countless variables that function within a company dealing in a global market that can have direct or indirect influence on their strategy. A successful company is one that understands and will anticipate and take advantage of the changes with the organization’s environment. There are technological, political and social external environmental factors and how they effect global and domestic marketing decisions. “The technological environment refers to any new technologies that create new products and market opportunities. Those developments are the most manageable uncontrollable force that is faced by marketers. Technology has an incredible effect on life styles, consumption patterns and the economy. The advances in technology can start new industries or can alter or destroy industries and will stimulate separate markets”. (Perreault & McCarthy, 3)

As Phillip Kotler states, “products have a limited life; product sales passes through distinct stages, each posing different challenges, opportunities and problems to the seller; profits rise and fall at different stages of the product life cycle; products require different marketing, financial, manufacturing, purchasing, and human resource strategies in each stage of their cycles.” (Kotler 2000) The rate at which technology can change has forced companies to swiftly adapt in terms of how they develop, price, distribute and promote their products. An example of technology that has changed and grown is the increased use of the email and Internet. Nowadays it is possible to send documents or pictures at the click of a button and the receiver would get it in a matter of minutes.

Political Impact

“The political environment includes the governmental or special interest groups that will influence and limit the various organizations or individuals in a given society. The organization will hire lobbyists to influence legislation and will run ads that state their point of view on ‘public issues’. The number of special interest groups has grown in number and power over the last three decades which puts more limitations on marketers. An example of this would be an example of response by marketers to special interests is green marketing, the use of recyclable or biodegradable packing materials as part of a marketing strategy. The social/cultural environment is made up of forces that will affect the society’s basic values, perceptions, preferences and behaviors. The US values and beliefs include equality, achievement, youthfulness, efficiency, practically, self-actualization, and freedom. The changes in a social/cultural environment affect the consumer’s behavior, which in turn will affect the sales of products. The trends in social/cultural environmental include individuals that will change view of themselves, others and the world around them whilst moving toward self-fulfillment. An example of this would be how the people at are showing commercials that show how the tobacco industry knew how addictive and harmful cigarettes are–not only for the person who is smoking, but how second hand smoke affects others as well”. (Perreault & McCarthy, 4)

“By assessing external factors will enable the company to position itself within its operating environment. A number of macroeconomic factors will have affected any company, and will continue to affect it. Environmental factor assessments help to gauge the direction and strength of the major trends that shape a particular industry. Sometimes these pose a threat whilst other times they can create new opportunities. In assessing the environment, it is important to find new business opportunities, new market places, and companies with which some form of cooperative arrangement can be developed” (Perreault & McCarthy, 4)

A marketing campaign does not have to be a commercial business campaign. The United Way, American Red Cross, and politicians are examples of this. The United Way and the American Red Cross campaign for funding. The funding needed to run the daily operations of the organizations, the funding to reach out to the individuals or groups. Politicians need funding to run their campaigns to get the message to the voters of their views. These non-commercial campaigns will need to listen to the desires of the donors. The campaigns success could be measured by funds raised, or lives effected. Marketing requires communication. Communication for a marking campaign is bi-directional, to the customer and from the customer. With feedback from the customer, a company’s marketing campaign can be tailored to fit the objective. The feedback will allow a company to measure whether the original campaign is effective or if a change is needed to the campaign. A successful marketing depends upon effective communication.

In 1990 this market accounted for 26 % of European exports, 22 % of Japanese exports, 27.5 % of South East Asian nation’s exports and 14 % of exports from the United States of America with a value in excess of 110 billion dollars. Given this importance a fundamental question must be the extent to which “Western” models of organizational marketing behaviour will be of relevance and use to marketers seeking to enter and develop this market. As noted, a review of the literature reveals comparatively little specific attention to this issue. Thus, the primary purpose of this article is to help firms with global orientations design more effective and efficient marketing strategies for operating in these markets. Whilst observation, experience and focused empirical research underpin our discussion the intention is to provide a broad agenda of issues to be taken into account in serving the Gulf market rather than make a theoretical contribution to the development of models of organizational marketing behaviour. (Abou-Ismail, 41-55)

That said a review of extant models of organizational marketing behaviour points directly to the role of economic, organizational and socio-cultural aspects as determinants of marketing decisions. Our review of these in the context of the Gulf market clearly shows that they suggest different outcomes from those to be found in Western markets. In terms of the economic dimension of the Gulf market reference has already been made to its importance — a factor which is frequently lost sight of because of its role as a supplier of oil. It is important to remember, however, that because of its dependence on oil prices demand in the Gulf market can oscillate widely from year to year. Another major economic factor which deserves attention is that whereas existing patterns of trade owe much to history the aggressive competition from Japan and other Far Eastern nations is rapidly eroding this source of advantage. In examining the organizational environment and its impact on marketing decisions five specific issues were considered: marketing tasks, the composition of the marketing group and its behaviour, the impact of bureaucracy on marketing decisions, the concept of time, and the influence of country of origin effects.

In terms of marketing goals a salient difference identified in the Gulf market is that whereas purchasing for manufacturing is important in Western and other markets it is probably the least important goal in the Gulf where marketing for resale dominates. Wholesalers and agents play a much more important role in these markets and this has important implications for the development of an appropriate marketing mix. In terms of the composition of the marketing group and its behaviour it was noted that whilst non-Gulf nationals may play an important role in such groups their actual influence and authority varies considerably in relation to that of Gulf nationals within the same groups. (Aamer and Ibrahim, 12-37)

Another important difference identified in the organizational environment in the Middle East is the role of bureaucracy. Given that bureaucracy has its roots in the Gulf area it is unsurprising that it still exercises considerable influence on marketing behaviour and decisions to this day. It is particularly noticeable in its impact on governmental marketing decisions which comprise between 30 and 60 % of all expenditures for countries in the region. The existence of bureaucracy clearly has important implications for marketing and especially the sales function which must be designed in light of the implications of such marketing structures. Added to this the Gulf national’s concept of time is very different from that prevailing in the Western world and will require a radically different approach by the sales function from that expected of it in Western markets. (Abou-Ismail, 13-19)

The importance of country-of-origin effects was touched on earlier in this conclusion and will not be elaborated further here save to say that traditional suppliers to these markets have little basis for complacency. The second major area discussed in this article was that of the socio-cultural environment which is very different from that of the Western world. Specific attention was focused on the social pressure which is derived from the tribal behaviour that is still a dominant phenomenon in the Gulf area. Gulf citizens have a deep orientation towards group welfare and prosperity which is quite different from the individualistic orientation which represents the basic pattern of behaviour in the United States and Europe. Similarly, gender issues demand particular sensitivity.

A sound understanding of this social behaviour is clearly vital to anybody intending to develop markets in the area. Many specific examples are cited to lend support to this claim. If it was in doubt before, the Gulf War has clearly confirmed the importance of the Gulf market. Whilst the general principles of marketing largely apply there are important differences in degree and application if one is to succeed. It is hoped this article has provided some insights into how to improve one’s competitive edge. (Abou-Ismail, 41-55)

Conclusion

Qatar international goods market is considered as one of the developing international market. In this regard, the study has examined the consumers’ behaviour towards many marketing mix components to the goods of the Germany, Italy, France and the US. To evaluate the consumers’ behaviour towards marketing mix elements thirteen marketing mix component have measured. And the marketing mix components have comprised in components such as package labels, maintenance services and so forth. We have studied six top goods exporters to Qatar. In this regard, the models have comprised of ninety eight consumers representing a cross-sections of Qatar’s consumers. We have find from hypothesis those ten out of thirteen marketing mix components in which the Japanese goods were ahead as compare to others.

Works Cited

Aamer, G.M. and Ibrahim, T.D. “Marketing and Its Role in Developing the Competitive Power in the Gulf Manufactured Goods” (2003),a paper presented at the 4th Gulf Industrialists Conference, Kuwait, 12-37.

Abou-Ismail, F.F. Marketing Management: (2001), Concepts, Applications, and Developing Performance, (Arabic), Dar E1 Nahda, Cairo13-19.

Abou-Ismail, F.F. “Reference Group Influences in the Uncertain Decision Making Process: (2002), Empirical Findings on Buying of Personal Investment Goods”, The Midd-East Business and Economic Review, Vol. 4 No. 1, pp. 41-55.

A1-Ateyah, A.H. “Imposed Taxes Upon Oil Consumption in Europe and Its Impact Upon Trade Barriers with Europe”, (2002), Ministerial Opening Speech, presented at the opening of the 2nd Conference on European and Gulf Industrialists, Qatar, Doha, 26-29.

Al Hammad, A. Behaviours of Saudi customers towards marketing aspects: (2006), an empirical investigation. Saudi Commerce & Economic Review, 29(September), 15-17. Baker, M., & Fouad A., I. Organizational buying behavior in the gulf: (2003). International Marketing Review, 10(1), 42-60.

Bhuian, S. N. Saudi customers’ behaviours towards European, US and Japanese goods and marketing practices: (2006), European Journal of Marketing, 31(7), 467486: Bhuian, S. N. (2006b). Marketing cues and perceived quality: perceptions of Saudi customers toward goods of the U.S., Japan, Germany, Italy, U.K. and France.Journal of Quality Management, 2(2), 217-234.

Cordell, V. V. Effects of customer preferences for foreign sourced goods: (2002), Journal of International Business Studies, 23(2), 251-69.

Chao, P., & Rajendran, K.N. Customer profiles and perceptions: (2003), country-of-origin effects. International Marketing Review, 10(2), 22-39.

Darling, J. R., & Wood, V. R. A longitudinal analysis of the competitive profile of goods and associated marketing practices of selected European and non-European countries: (2000),

Journal of International Business Studies, 21(3), 427-50.

Dunkley, Clare. The Doha market’s deepening pool. MEED: 2005, Middle East Economic Digest, 00477230, Vol. 49, Issue 3, 16-18.

Ettenson, R., Wagner, J., & Gaeth, G. Evaluating the effect of country of origin and the made in U.S.A.’ campaign: (1998), A conjoint approach: Journal of Retailing, 64(Spring), 85100, 127-33.

Klenosky, D. B., Benet, S. B., & Chadraba, P. Assessing Czech customers’ reactions to Western marketing practices: (2006), a conjoint approach: Journal of Business Research, 36(2, June), 189-198.

Shimp, T., & Sharma, S. Customer ethnocentrism: construction and validation of the CETscale: (1997), Journal of Marketing Research, 24, 280-89.

Tosi, H.L. and Carroll, S.J. Management, (2002), 2nd ed., John Wiley and Sons, New York, pp. 1617-28.

Yaprak, A., & Baughn, C.C. The country of origin effect in cross-national customer behavior: (2001), rising research avenues. Proceedings of the Fifth Bi-Annual World Marketing Congress of the Academy of Marketing Science, pp. 263-69.