Abstract

This paper analyzes the performance of Canada and America in mitigating the effects of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. There are many reasons advanced for Canada’s better performance throughout the crisis, but this paper mainly focuses on the cultural and lobby forces that distinguish both systems from one another. Nonetheless, this paper also acknowledges that the differences in policy frameworks between the two economies are also accountable for the difference in the performance of the two systems throughout the crisis. Comprehensively, we affirm that Canada’s financial system is old-fashioned and conservative while the US financial system is very liberal.

Canada’s business culture is, therefore, risk averse while America’s culture is less risk averse. These dynamics explain the varying business cultures between the two countries. Less aggressive lobby forces also characterize Canada’s conservative business culture, whereas the US financial market is characterized by extreme lobby forces on government, most notably from Wall Street. These dynamics characterize the remarkable difference in banking performance between the two countries.

Introduction

The 2008 global financial crisis (GFC) has been perceived to be among the world’s greatest financial crises. Its severity can only be compared to the Great depression of the 1930s (Kaar, 2009). The extent of the crisis was immense because it affected the operations of major world financial institutions, stock markets around the world and the mortgage market, which saw many people lose their homes. The impact of the GFC was severe on the US economy because it almost affected all aspects of the socio-economic environment. It is reported that the total output of goods and services in the American economy decreased by a yearly average of 5%, while the unemployment rate soared to an all-time high of 10% (Kaar, 2009). It is also reported that the annual hours per week that American citizens worked also decreased to about 30 hours (Kaar, 2009). These economic statistics were last reported in America during the great depression and subsequent economic crises of the eighties.

The GFC also brought a significant and uneven distribution of wealth among Americans. For example, it was reported that a majority of rich Americans were not severely affected by the crisis. The middle class was the most affected population group because they constituted a majority of the population that took mortgage loans. The uneven impact of the GFC, therefore, brought an uneven distribution of wealth because 1% of the American population, which owned about 35% of the wealth, ended up increasing their wealth to about 38% of the national wealth by the end of the crisis while the poor remained poor (Kaar, 2009). Similarly, it is estimated that wealthy Americans – just at the bottom of the top pyramid level – were significantly affected.

Comprehensively, investigations by the federal government showed that more than 60% of all American households reported a decline in wealth (Kaar, 2009). The ripple effects of the crisis reverberated across the economies of major western powers, leading to massive unemployment and reduced consumer wealth. The pessimism expressed, regarding the future of the world economy, further led to decreased economic activities, which was partly attributed to the prolonged recession in 2008.

The GFC greatly affected the economies of major western powers because it dented different components of the world economy including the stock market, operations of financial institutions, credit markets, the shadow financial system, and consumer wealth. In fact, the 2007 GFC also contributed to the collapse of some of the world’s major economies. The negative growth rates reported in America, the United Kingdom, and the Euro zone are just a few examples of the effect of the GFC during the 2007/2008 period. In Iceland, the GFC caused the collapse of the country’s three major banks: thereby affecting the operations of the country’s banking system (Sun, 2011, p. 2).

When the impact of the GFC is quantified alongside the size of Iceland’s economy and geographical size, it is estimated that Iceland suffered among the worst economic crisis in the GFC period. The US, which was perceived by many economists as the strongest consumer block, suffered increased consumer savings and fewer investments. Since Sun (2011) estimates that about a third of the global consumption of goods and services between 2001 and 2008 can be traced to the US consumer, the collapse of the US economy was therefore set to dent the economic prospects of most countries around the world.

The drastic change in consumer perception led to a decline in economic growth for some countries because many US consumers were hesitant to invest their money overseas. For example, Mexico, which depends on the US for its economic growth, suffered a 21% fall in GDP (Sun, 2011, p. 5). The same situation was also mirrored in some European and Asian economies such as Japan, Germany and UK, which all share a close business relationship with the US, because these economies reported decreased GDP rate of 15%, 14% and 7% respectively (Sun, 2011, p. 5).

The GFC also accounted for the slow growth of most developing economies in Asia and Africa. For example, Cambodia’s economic growth declined to a near zero after it fell from an all-time high of 10% in 2007 (Sun, 2011). Kenya, which had achieved an economic growth forecast of 7% in 2007, also suffered reduced economic growth forecast of 4% after global fund remittances dropped due to reduced remittances of dollars from migrant workers living in the US and other developed nations. The GFC was also cited as the top reason for dwindling standards of living in some of India’s cities, such as Bangalore, while Ghana suffered reduced trade because the poor state of western economies accounted for reduced trade in these countries (Sun, 2011).

Interestingly, the impact of the GFC was not severe across all economies of the world. In fact, it is estimated that some of the world’s leading developing economies were able to weather the financial storm (Batten, 2011). For example, most Arab economies still maintained favorable balance of payment figures because their economies were not very dependent on western nations. For example, unlike most African countries, many Arab states are not highly dependent on western aid. However, the GFC only posed a danger to Arab economies due to falling global prices of oil, which stemmed from a decline in the demand for oil globally. Oil is the single most common denominator for evaluating the performance of Arabian economies. The ripple effect of low oil prices is reduced investments and high unemployment levels, especially of foreign workers who work in the oil industry. Nonetheless, most Arabian economies were able to enter the GFC from a relatively stronger position.

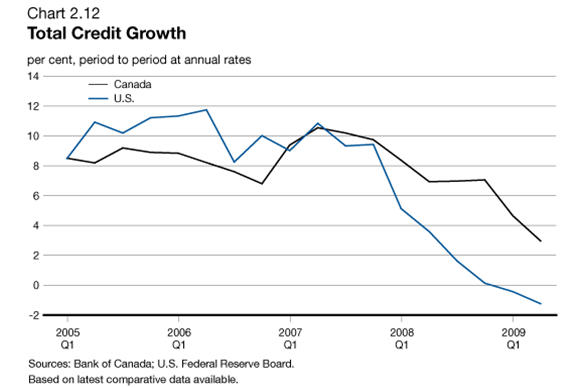

Canada is another country that weathered the effects of the global financial crisis because, considering the approaches taken by other countries in bailing out their economies, the Canadian government fared relatively well in policy implementation to wade of the global financial crisis (Navarro, 2011, p. 87). Comparing the performance of the US and Canadian economies, we can see from the diagram below that Canada fared relatively well throughout the 2007 GFC

In fact, from the above diagram, we can see that Canada and the US started on an equal footing in 2005 but owing to the different policy paths undertaken by the two nations; both countries have had different economic fortunes. Both countries seem to have had a level economic stability throughout the years preceding the 2007 GFC but after the crisis, the US’s economic growth took a significant dip. Even though the Canadian economy was slightly affected, it registered a lesser impact of the crisis. In fact, Canada’s economic decline was rather gradual, but its banking performance was relatively strong. The US’s impact was however drastic.

Nonetheless, the above dynamics greatly mirror the overall economic performance of the two western nations. Focusing on the banking sector, we see that Canada’s performance throughout the 2007 crisis was very good (Department of Finance Canada, 2011, p. 2). In reference to the above assertion, the World Economic Forum has consistently ranked the Canadian banking system to be among the most effective financial systems in the world today (Navarro, 2011, p. 87).

Canada’s resilience to overcome global financial crises has not only been documented in the 2007 financial crisis alone; even in the great depression of 1930s, no Canadian bank collapsed. For Canadian banks, government intervention was unnecessary during this period even though thousands of US banks collapsed, and similar banking crises were also reported in Germany and Italy (following Austrian banking crisis of the 1930s). During the great depression, it is reported that all the 11 Canadian banks, which were projected to be affected by the crisis, survived the crisis. Unlike other banks, which received government bailouts, the 11 Canadian banks did not receive any state bailouts. Due to the remarkable record by Canadian banks, international financial agencies have rated Canada’s banks to be leveraged at 18:1 while American and European banks have been leveraged at 26:1 and 61:1 respectively (Navarro, 2011, p. 87).

Canada has, therefore, gained international recognition for employing sound economic policies during the 2007 global financial crisis. Canada’s policy makers have also received praise for developing a “prudent” economy that provides the right financial environment for economic success (Navarro, 2011, p. 87). Canada’s strong financial institutions have not only been acknowledged in its domestic market but internationally as well. For example, the Bank of Montreal has been ranked to be the tenth largest bank in America, in terms of market capitalization, thus beating most American banks (Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 2010, p. 47).

It is also reported that three of Canada’s strongest banks make Bloomberg’s list of the world’s strongest financial institutions. Department of Finance Canada (2011) and the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (2010, p. 47) explain that the above strengths have affirmed Canada’s role in helping other world economies to recover from the 2007 GFC.

In this regard, Department of Finance Canada (2011) explains that Canada’s lesson to the rest of the world is highlighted in its role to identify economic opportunities even in bad economic times. Department of Finance Canada (2011) further explains that when economies prepare themselves for bad times and take decisive actions when there is a need to; there is bound to be a good possibility of overcoming bad financial times.

Many experts identify the good oversight of the Canadian government over its financial system as one reason for Canada’s success in wading through the GFC. Other experts note that the effective regulatory framework established by the Canadian government and the effective lending standards in Canada’s housing market are also some of the reasons for the success of the Canadian economy in the GFC (Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 2010, p. 47).

The 2007/2008 global financial crisis has been compared with previous financial disasters such as the great depression. However, GFC provides us with the most valuable lessons about today’s financial environment. Over the past decades since the great depression, there have been tremendous strides made in the provision of financial services. Similarly, financial institutions have developed more innovative and creative products.

As a result, today’s financial environment is in sharp contrast to the regulatory environment of the 20th century. In fact, a country’s regulatory environment can no longer operate in isolation because of the global pressures of the world economy; therefore, many regulatory policies are influenced by other regulatory policies from other countries. In addition, in today’s financial world, different economic blocks have emerged. These economic blocks have a profound impact on the way different countries manage their financial affairs. Similarly, their influence has prompted many countries to align their economic practices with other countries around the world.

From the above understanding, the recent global financial crisis (GFC) has stressed the influence of global economics on domestic markets. Thus, the economies of different countries around the world are closely intertwined. It is now more difficult for one country to survive or experience an economic crisis without other economies being affected.

The global economy has been intertwined by increased trade among world economies -in the form of imports and exports. The provision of grants and loans are also other avenues that support the integration of world economies. For example, most western nations import raw materials and goods from developing nations while many developing nations import finished products from the developed world. The reverse is also true because some developing nations perceive the western markets as some of their primary markets. Therefore, if an economic crisis occurs in the developed world, market activities in the developing world would be severely affected. The sheer impact of financial disasters on world economies emphasizes the importance of knowing how to mitigate the risks associated with global financial disasters.

The above lessons seem to have been learned by countries, which managed to reduce the impact of the GFC on their economies. Evidently, this paper has cited the resilience of major economies in the Arab world and some western powers such as Canada in overcoming the GFC. However, at the center of this observation is the policy and regulatory framework adopted by different countries during or before the GFC.

Since Canada shares many aspects of its political, economic and social life with other western powers, it is interesting to evaluate how the country managed to overcome the GFC. Experts observe that the successful policy implementation of the Canadian government to wade off the 2007 GFC was a successful policy adoption by the Canadian government, but this paper holds the view that the divergent business culture and practices that the Canadian economy has greatly informed its resilience to overcome the GFC (Robinson, 2009, p. 3). This paper also proposes the view that the divergent activities of the banking lobby group within Canada and the US added to Canada’s push to overcome the GFC.

To confirm the above views, this paper will embark on a comprehensive analysis of different financial publications and expert reviews regarding the aforementioned theories. The findings of this paper greatly rely on the analysis of relevant literature regarding the research topic and expert views regarding the same. However, focus will mainly be directed to the differences between the Canadian banking system and the US (as opposed to the difference between the Canadian banking system and the banking system in western economies). The findings of this paper will be useful in understanding the financial systems of both countries. The findings will also help understand the pitfalls of existing financial systems with the aim of making recommendations to avoid future possibilities of similar financial crisis.

The Global financial Crisis

Causes of the Global Financial Crisis

As the global financial crisis spread across the US economy, the disaster was quickly politicized as a weakness of the Bush administration. Critics blamed the Bush administration for failing to take adequate measures to stop the crisis in good time (Kaar, 2009). Many experts agree that the shortcomings of the former administration fueled the spread of the crisis. However, these views are as divergent as the real causes of the global financial crisis.

Consequently, many books, articles and publications have tried to explain the disaster in their unique ways. The role of the Banking institution has featured in many of these articles because many experts blame valuation and liquidity problems in the US banking system as some of the prime reasons for the occurrence of the 2007/2008 global financial crisis. In addition, prior to the year 2007, the US housing market enjoyed increased consumer confidence while the stocks attached to the industry were highly valued (Kolb, 2010, p. 392). Nevertheless, after the housing bubble burst, there was an almost simultaneous plummet of stocks attached to the real estate market.

The high stock valuation for the real estate sector started when the US housing market boomed during the 2005-2006 period when banks started lending a lot of money to the American public for home purchases. Initially, the US government had provided a financial incentive to commercial banks to offer home financing options to US citizens. The interest rates were therefore low, and many people had access to home financing options. These financing options led to increased investments in the housing sector, and hence created the housing boom. Many international investors were also attracted to this market (Kolb, 2010, p. 392).

The easy access to credit caused a sharp rise in the prices of residential properties as a result of the increase in demand, which in the end led to the housing bubble. As the financial crisis loomed, banks encouraged people to take up loans for home purchases despite the sudden rise in default rates. The banks believed that the homeowners would be able to quickly clear the loans, but they overlooked the high interest rates that were attached to such an arrangement (Kolb, 2010, p. 392).

Financial lending institutions were also in a rush to consolidate their market share in the mortgage market, thereby overlooking the importance of vetting customers for their credit worthiness. Here, there was a strong growth of subprime lending because banks relaxed their requirements for credit lending. For example, subprime lending was only estimated to be about 10% of all the mortgages in the US but in the 2005-2006 periods preceding the GFC; subprime lending was at an all-time high of 20%. Therefore, the lending environment became very risky.

Many homeowners were, therefore, unable to repay their loans due to high interest rates and home prices subsequently fell. Foreclosure rates also increased significantly. As a result, Investors who had tied their money in the real estate sector suffered severe losses and consumers who had taken up loans and mortgages suffered decreased wealth levels. The banks also had their financial strength weakened due to increased default rates.

Some researchers identify a combination of several financial factors such as conflict of interest, increased deregulation of the financial markets and a sophisticated array of financial products as some of the real causes of the GFC. Kolb (2010) explains that as the housing market started and continued crashing, there was a great financial incentive to foreclose homes. He adds that as the housing bubble grew, the regulatory environment was stuck up on letting the financial market expand without proper regulation. There was no pressure to reveal financial information (activities) by different banks, and therefore, many oversight activities happened in the financial sector.

After probing the 2007 GFC, it was reported that the government overlook investment banks as strong financial institutions that had an almost similar power as commercial banks or other agencies that lend money to the government (Kolb, 2010). Their activities were, therefore, quite significant to the economy, but they were not subjected to the same regulations as commercial banks.

The poor underwriting framework for the mortgage industry was also partly blamed for the GFC. In a recent report detailing the findings of an investigation probing the GFC, it was established that, in 2006, about 60% of all the mortgages underwritten during this period were fraudulent (Kolb, 2010). The fraudulent underwriting policies were attributed to the lack of sufficient documents for the underwriting process and the failure to observe laid out underwriting policies. For example, in 2007, it was estimated that about 80% of all mortgage deals overseen by Citi (a financial loan lender) were defective. Upon further investigation by an inquiry probing the GFC, Clayton holdings (another financial loan lender) announced that upon the review of close to a million mortgages taken between 2006 and 2007, only about 54% met the required financial standards for proper mortgage provision (Kolb, 2010).

Upon further inquiry, it was established that about 28% of all loan arrangements done during this period did not meet the requirements for any loan issuer. Further investigations showed that about 30% of the mortgage arrangements that did not meet the minimal requirements for any issuer were subsequently sold to different investors in the housing market (Kolb, 2010). These mistakes only added to the complexity of the US housing market, which subsequently led to the GFC. In fact, in subsequent months (after the disaster), private security companies found it difficult to recover from the losses accrued from poor mortgage underwriting.

Instances of increased debt burden and over-leveraging are also some of the reasons cited as the causes for the global financial crisis. It is reported that prior to the crisis, financial institutions were highly leveraged and, therefore, they engaged in many risky investments without properly formulating strategies to mitigate these risks. Moreover, complex financial instruments were used to leverage these institutions, thereby reducing the investor and regulatory oversight of the activities of these financial institutions. It is estimated that most US financial institutions were highly indebted, a few years preceding the GFC, thereby reducing their resilience to manage the risk created by the GFC.

The complexity of these financial leveraging instruments also made it very difficult to restructure such financial institutions during times of financial crisis, thus prompting the need for government intervention, especially during bankruptcy. Kolb (2010) explains that there was a lot of free money in the hands of US consumers such that when the housing bubble grew, the home equity fund almost doubled, from about $630 billion to $1430 billion. It is also projected that the percentage of home mortgage debt to gross domestic product (GDP) increased from a mere 47% to about 78% during the GFC. Comparing the American household debt during the same period, it was established that this ratio increased from a mere 77% in 1990 to about 120% in the preceding years before the GFC (Kolb, 2010).

In addition, comparing the American private debt percentage during the 80s and the GFC period, it is reported that the debt levels doubled from about 124% to 291%. It is also reported that the top five US financial banks accumulated a total debt of about $4.1 trillion in the preceding years before the financial crisis, and hence increasing their vulnerability to the GFC. Kolb (2010) explains that this figure was about 31% of the American nominal GDP.

The level of financial innovation and complexity of financial products are also said to have caused the global financial crisis. Before the onset of the GFC, many financial institutions embarked on a spirited effort to churn innovative financial products. This move was intended to consolidate their market share, but, unfortunately, some of these products were highly sophisticated for the average US consumer to determine their impact on their finances. The credit default swap is one such product that was developed during this period.

The increased innovation in financial products added to the complexity of financial reporting and regulation. The number of players in the provision of financial products also increased, thereby adding to the complexity of financial reporting. Many financial institutions, therefore, relied on unverified information from third party financial players, adding to the complexity of financial risk underwriting. This environment created a good platform for fraudulent financial transactions and unreliable mortgage underwriting. The complexity of developing sophisticated financial products facilitated the circumnavigation of regulations by some financial institutions, and thereby creating an unregulated shadow financial system. This environment added to the collapse of the financial market.

Again, Kolb (2010) explains that there was a failure by credit rating agencies and governments to ascertain the true risk associated with the housing market. Many markets had a difficult time trying to determine the correct risks associated with the financial markets because many banks were not transparent in exposing their risk factors. The failure to ascertain the true market risks associated with the mortgage market made the industry grow larger than it should have done.

The incorrect assessment of financial risk also led to the rapid spread of the financial crisis from the mortgage market. In addition, many experts also found it difficult to assess the risk attributed to financial innovation. For example, the collapse of AIG was an indicator to the incorrect assessment of risks because the insurance company insured against losses that it could not effectively manage. Therefore, as the GFC progressed, the company could not process the claims brought to it. This situation led to the eventual takeover by government in 2008.

Kolb (2010) explains that the complexity of financial products increased the concern among many investors in the real estate sector, but since many international credit rating agencies validated the complex financial instruments, many investors overlooked the risks associated with complex financial instruments. Later, when the financial crisis grew out of hand, the government was caught off-guard and did not know how to correctly ascertain the risks associated with the mortgage market. The sub-delegation of responsibility started after the government started relying on commercial banks to ascertain this risk. Unfortunately, the credit rating agencies also relied on the same institutions to evaluate the market risks.

These institutions had unique stakes in the financial crisis, and, therefore, the information given was skewed. Furthermore, there was a strong global appetite for investments and fund managers kept investing their client’s money in overpriced investments, which could not give the right yields that clients expected (Kolb, 2010). The role of the government in the GFC was, however, limited to the poor regulatory practices adopted by the federal bank to curb the disaster. The government’s role was also highlighted in the 1999 repeal of the Glass Steagal act, which eliminated the distinction between Wall Street and depository banks. This move was perceived to have fueled the financial crisis (Kolb, 2010).

The 2007 GFC can also be attributed to the weakness in the architecture of the US financial system. REVEUES (2009) explains that there was a shadow banking system that introduced new weaknesses to the country’s financial systems, thereby making it (more) prone to the 2007 housing bubble. The main element in the architecture of the US financial system is the interaction between mainstream banking institutions and other financial institutions in the US. For example, non-banking financial institutions were allowed to issue papers, while this was a mainstream preserve of commercial banks.

Indeed, several financial institutions like AIG, Lehman & Berns (investment banks but not real banks) issued financial papers while mainstream banks were side-lined (REVEUES, 2009). This was an overlap in the roles of the banks and other financial institutions in the country. Consequently, the activities of the non-banking financial institutions created a shadow banking system which was difficult to regulate. This system created a weakness in regulation for the US banking system.

Another element in the US financial system that created a weakness in regulation was the uptake of origination fees and increased securitization in the mortgage market (Petroff, 2007). Indeed, as explained in earlier sections of this paper, lenders and investors (backed by the default mortgages) suffered immensely from the burst of the housing bubble. Concisely, most of these companies filed bankruptcy (soon after the mortgage market crash) because they were left with mortgages that were worth less than what they were actually valued.

However, instead of cutting their losses and remaining with whatever property value was left from the market crisis, these firms decided to participate in the secondary mortgage market by collecting originating fees and selling off the bad mortgages (Petroff, 2007). This trend was witnessed among many companies and instead of helping the economy it worsened the situation. However, after analyzing this trend from the perspective of the investors, the move to sell bad mortgages was sure to give them a profit but after analyzing the entire situation from the national economic perspective, it worsened the economic situation in America.

Petroff (2007) reports that it would have been a better move for the investing companies to hold on to the originated mortgages (in their books) because the move to sell off the mortgages freed up more capital and created more liquidity (in turn leading to more lending). Through this strategy, the snowball began to pick momentum because there was a subsequent demand of the secondary mortgages which later pooled together into a security. These securities were later conceptualized as collateral debt obligations and later sold to investors (investment banks) who securitized them into bonds. These bonds were later sold to investors as collateral debt obligations (Petroff, 2007).

Concerning the financial environment preceding and after the 2007 GFC, Wharton school identifies several policy reforms that ought to be implemented by different governments to avert such a crisis. Wharton school identifies the establishment of strong global governance policies as one way of stabilizing world economies (Freeland, 2010). However, in the same breadth, it also acknowledges that such a task may be difficult to do because world powers keep changing by the day, especially with the growing number of emerging economies.

Another policy change that needs to be established is the implementation of self-regulation policies, which are supposed to cushion world economies from adverse economic conditions. This recommendation is in line with the lessons learned from the resilience of the Canadian economy in overcoming the 2007 GFC. These lessons emanate from self-regulation measures adopted by the Canadian government to protect its domestic economy from adverse economic conditions.

Wharton school also proposes the expression of humility by policy makers when comprehending the complexities of the economy (Freeland, 2010). More so, Wharton school proposes that policy makers should acknowledge the growing complexity of financial products in today’s economies and the complex implications that they pose to the domestic economy (Freeland, 2010). Lastly, it also suggests that economies should be more wary about the weaknesses of operating on a global front (Freeland, 2010).

These recommendations are informed by the complexities of operating internationally, such as over-indulgence and excessive greed. Operating on the global financial market also means that economies need to be wary of the trade imbalances among different nations, the failure to have global institutions that oversee global trade and the subsequent lack of regulations to govern international trade. Since the global financial market poses new risks, there is an even greater importance of adopting a multidisciplinary approach to evaluate the risks posed by such type of an environment. The failure to understand the complexities of global risks accounts for the vulnerabilities of the financial markets to shoulder the weaknesses of the financial system.

The importance of forging public-private partnerships can also not be underestimated because regulators and policy makers often experience cognitive limitations for understanding financial risks. Public private partnerships would, therefore, provide a long-term foresight to the global risks surrounding the marketplace and evidently curb the abuse of market powers. Preventing the abuse of market powers is a very important addition to be adopted if future market catastrophes are to be avoided. The declined quest to merge by some of Canada’s big banks can explain this phenomenon because the government declined such efforts. If these banks merged, they would create a strong center of power, which could be used to wield excessive authority on the country’s financial system.

Comparison with Previous Financial Crises

As mentioned in earlier sections of this paper, throughout the world’s financial crises, the 2007/2008 GFC can be best compared to the great depression. Many people often wonder how both crises could be compared while the economic environment between the late twenties and now are very different. However, what many people fail to understand is that the economic fundamentals between the American economy during the great depression and now are very similar (Arnon, 2010, p. 248). More surprising is the fact that both disasters were caused by almost similar causes. After analyzing the similarity between the 2007/2008 GFC and the great depression, many people wonder why the government and all relevant authorities have not learned the economic lessons of the great depression.

Arnon (2010) points out that a strong similarity between the great depression and the 2007 GFC was the fact that a very small minority of the American economy owned a lot of the nation’s wealth. Another similarity identified by Arnon (2010) is that preceding both disasters, the American economy enjoyed a period of economic boom that lasted close to a decade for both periods. Interestingly, the 2007 GFC can be traced to the 1857 financial crash when there was a lot of speculation regarding land transactions, especially in the western part of the US (Martin, 2011). Similarly, during the housing bubble – witnessed before the 2007 GFC – many corporations such as railroad companies and banks profited handsomely from the land transactions. Unfortunately, most of the money accrued from the land transactions were amassed by America’s wealthy population. It is estimated that most wealthy Americans owned about 25% of the country’s wealth during the time (Arnon, 2010).

The 1920s period was characterized by economic boom because America was quickly elevated to a world power after it won the First World War. This period was also characterized by rapid industrialization and throughout the nation; there was a lot of jubilance (Martin, 2011). Again, like the 1850s period, most of the economic benefits enjoyed during this period (1920) never trickled down to the poor. Majority of wealthy Americans enjoyed all the economic benefits by themselves. Almost like a pattern, by the end of the 1920s period, the rich controlled about 30% of the nation’s wealth (Arnon, 2010).

Comparing the 1920s period to the 2007 GFC, we can see that the rich also enjoyed a period of economic boom before the crisis (Gilbert, 2008). As noted in earlier sections of this paper, decreased regulations, occasioned by the repealing of the Glass-Steagal act, prompted the rapid sale of securities and the extensive sale of mortgage products (Kravitt, 1997). The rich enjoyed handsome profits during this period and almost like karma, they controlled close to 30% of the nation’s wealth (Arnon, 2010).

When the economic bubble burst, the impact of the disaster was greatly felt by the middle class and the poor. Hopely (2011) notes that, such periods of economic boom (such as the 1920s and 2007 economic booms) were bound to end at some point because they were unsustainable. Therefore, when the 2007 housing bubble burst and the rich controlled most of the nation’s wealth, it became impossible for ordinary Americans to purchase goods and services produced by the economy, and hence. as the news of a financial crisis spread rapidly through the US, the possibility of experiencing an economic depression was inevitable because the public withheld the little money they had in anticipation of bad economic times. Such kind of a scenario is likely to decrease the national demand for goods and services. The decreased national demand caused many factories to shut down, thereby rendering most workers unemployed. This scenario was witnessed during the great depression and the 2007 GFC.

The great depression and the 2007 GFC were also similar in the sense that both crises were characterized by financial and economic vulnerabilities, which were preceded by periods of sophisticated financial innovation (Fauchald, 2010). The financial vulnerabilities witnessed during the great depression can, however, not be equated to the 2007 GFC because the great depression had a stronger impact on the US economy as opposed to the world economy. Nonetheless, since many decades have passed and the forces of globalization have taken over, the 2007 GFC reverberated across major economies of the world. The financial and economic vulnerabilities of the 2007 GFC were, therefore, more profound for the GFC because other economies were vulnerable to the US-centered crisis (Fauchald, 2010).

Liquidity and funding problems are also cited as some of the common challenges that plagued the 2007 GFC and the great depression. The great depression was characterized by a period of depository erosion by banks while there were no strong insurance structures to mitigate the effect of such a disaster. It is estimated that three years into the great depression, about a third of US banks collapsed (Martin, 2011). However, for the GFC, there was a slight difference in the intervention of insurance firms.

Since the global economy is currently intertwined in the economic activities of different countries, the spillover effects of the great depression were relatively slow because their effects were only realized from the capital flows between the US and other countries.

Regarding policy implementation, there has been a strong response in policy support for the 2007 GFC compared to the great depression (Fauchald, 2010). During the great depression, there was a strong lack of countercyclical policy responses because the regulatory framework was not well informed, as it is the case today. The central banks’ role in most affected nations of the 2007 GFC have been swift because these institutions have tried to improve the liquidity level of affected banks. Similarly, central banks have tried to lower policy interest rates. For example, the US embarked on providing a strong fiscal stimulus to boost the aggregate demand within the economy (Fauchald, 2010). Though some experts have criticized this policy strategy, they have been seen to have a largely positive impact on the economy.

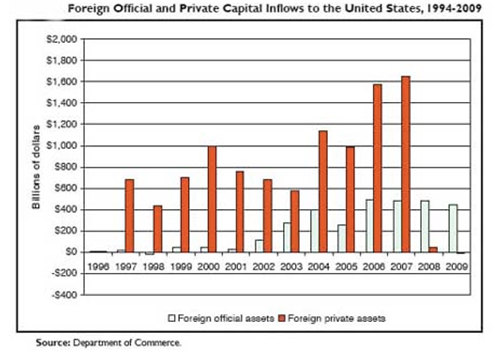

Considering the dynamics of the 2007 GFC and other global financial crises, Hopely (2011) attributes most of the similarities among the crises to the regulatory environments of the time. He explains that the periods preceding the financial crises were characterized by decreased regulation and heavy capital inflows. For example, preceding the 2007 financial crises, there were many capital inflows into the US economy from the Asian markets and oil producing countries in the gulf. The following diagram shows that, just before the 2007 GFC, the capital inflows to the US peaked.

These capital inflows met a deregulated economic environment. The heavily deregulated environment that preceded the great depression and the 2007 financial crises are also cited as the main reasons for the inability of the economy to shoulder financial shocks (Fauchald, 2010).

Hopely (2011), however, draws another parallel between the 2007 financial crisis and the financial crisis of the 70s by noting that the role of the US banking system was mainly to act as an intermediary between oil exporters and many borrowers from emerging countries, especially Latin America. The intense capital flows of petro dollars subsequently led to a debt crisis that mainly characterized the financial environment during the 80s. This debt crisis subsequently put a lot of pressure on money-centered banks.

Hopely (2011) explains that most of the oil revenues from oil producing countries were mainly being held in the US, but many borrowers in the emerging markets were registering surpluses. There was more lending than borrowing, which occurred at the time. Essentially, there were more petro-dollars recycled in the US economy in the name of emerging markets, which interestingly existed within the US borders. Hopely (2011) also explains that more than a trillion dollars was given to borrowers in the mortgage market, but unfortunately most of these borrowers were the least credit worthy. Here, a financial crisis clearly loomed.

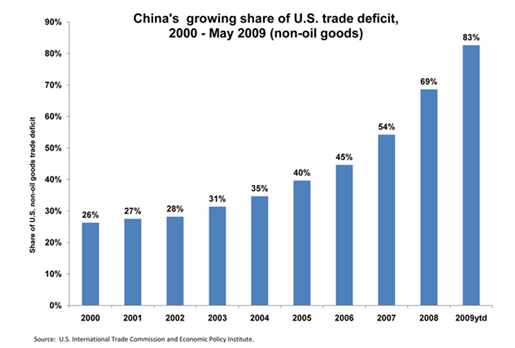

The US trade deficit with China also mirrors the same economic situation between the US and its Southern neighbors. Currently, the US has an enormous trade deficit with China which is worth about $295 billion (according to 2011 figures) (Amadeo, 2012, p. 1). Comparatively, this figure is extraordinarily high considering the trade deficit between the US and China was only $273 billion in 2010. The 2010 and 2011 figures are the highest trade deficit figures between the two countries (ever) (Amadeo, 2012, p. 1).

The US-China trade deficit is considered interesting because it is the highest, in a period when US exports are at an all-time high. In 2011 alone, it was estimated that US exports to China were well over $100 billion (a figure that rivals 2010 figures of $91.9 billion) (Amadeo, 2012, p. 1). On the other hand, US imports from China have consistently increased to about $399.3 billion while in 2010; the figures were only $364.9 billion (Amadeo, 2012, p. 1). Since this study focuses on the 2007/2008 period, it is important to note that the trade deficit between the US and China has been consistent throughout the GFC period. The following diagram shows this trend

The enormous trade deficit between the US and China has a negative impact on the US economy. Amadeo (2012) explains that China is now among the biggest lenders of the US and as of 2011, the US owed China about $1.3 trillion. This amount accounts for about a quarter of the total US public debt (Amadeo, 2012, p. 1). Such a high public debt level has not only been reported recently, but it has also been growing throughout the 2007 GFC. Therefore, the US economy has been at a disadvantage (economically) to meet it economic obligations and similarly, its strength to shoulder the effects of a melting economy has been significantly diminished. This factor contributed to the spread of the 2007 GFC.

Even though the above parallels largely hold true for the US financial crisis, the same mechanisms have been applicable in other financial crises in the UK, Spain and other countries that have experienced similar financial disasters (Martin, 2011). From the analysis of the 2007 financial crisis and previous financial disasters, such as the 1907 financial panic and the 1929 financial crisis, it is correct to report that the financial dimensions of the 2007 GFC were not very different from previous financial disasters (Fauchald, 2010).

Government Response to the Disaster

To the extent that economic outcomes are dictated by the activities of different market players, the role of the government in mitigating the effects of the 2007 GFC was very profound. Different governments undertook different strategies in dealing with the 2007 GFC crisis, but common among the strategies adopted by most western powers was the introduction of economic stimulus packages to boost economic performance (Wright, 2010, p. 48). Japan, U.S and France are among the countries that adopted this strategy. Some nations like China and the US poured hundreds of billions of dollars to their stimulus package plans, while the European Union used two hundred billion Euros for the same purposes (Castle, 2008, p. 1). The following diagram shows the percentage in inter-government spending that the US and some European countries used in the crisis.

In 2008, it was reported that China, for a very long time, reduced its interest rate to set the precedent for other Asian countries like Indonesia, which also reduced its repo rate by almost equal margins. Most of the Chinese stimulus packages were aimed at increasing government spending in important economic areas such as infrastructure growth. However, social welfare programs also stood to benefit from the stimulus package.

The impact of the 2007 GFC was strongly felt in China because the country’s economy was mainly characterized by exports to the western world, most notably the US. The reliance on the export sector encouraged the introduction of tax rebates on exports goods involving rigorous labor inputs. The announcement by the Chinese government that it was going to introduce a stimulus package was received well by world leaders who reported an improved sense of optimism in the international marketplace because China played a crucial role in stabilizing the global economy.

Among other Asian powers, Japan decided to inject more than 29 billion dollars into its banking system (Wright, 2010, p. 48). Taiwan responded by reducing its reserve ratio to boost economic development. Australia was reported to have injected more than one billion dollars into its banking system to insulate it from the extremes of the GFC. This estimate (more than one billion dollars) was projected to have tripled the market estimate for the industry. India also adopted the same approach of injecting more than a billion dollar to its banking industry (Wright, 2010, p. 48).

The European response to the global financial crisis was initially limited to Spain and Italy because it was believed that these countries required significant reforms in their housing sectors. With this focus in mind, policy makers agreed that introducing tax rebates would be an important fiscal policy to boost the country’s housing market. Two hundred billion Euros were set aside for this purpose (Castle, 2008). As mentioned in earlier sections of this paper, UK, Spain, Germany, and other European states introduced numerous stimulus packages to boost their economies in the wake of the financial crisis. In the German economy, Hypo real estate was bailed out by the German government and in the UK, an ambitious 500 billion Euros stimulus plan was introduced to boost the economy (Wright, 2010, p. 48). This stimulus package was mainly intended to boost the country’s banking sector.

As the 2007 GFC progressed, there were growing pockets of resistance across the European Union for introducing more stimulus packages. Many policy makers shared this resistance across Europe. For example, the German finance minister expressed deep reservations regarding the provision of stimulus packages. His sentiments contributed to growing sentiments against the US-style economic ideals of increasing the budget deficit in the hope of boosting economic activity (Wright, 2010, p. 48). However, comprehensively, many observers perceive Europe’s response to the crisis to be similar to America’s.

Canada was among the countries that were greatly shaken by the 2007 GFC. Indeed, the country was at par with most of its western counterparts in experiencing the effects of the GFC. Naturally, Canada was bound to experience the same economic fortunes that hit other western economies. However, interestingly, the Canadian government did little to prevent its economy from the effects of the 2007 GFC. Other countries embarked on rigorous policy reviews and the provision of stimulus packages, but the Canadian government never adopted any of these approaches. Essentially, the government adopted a wait-and-see approach. This strategy was informed by the government’s trust in its domestic economy.

Canada’s response to the 2007 GFC can be best understood against the backdrop of economic reforms undertaken by Jean Chretien’s administration (Chretien was voted as the country’s prime minister during the 90s). His government was greatly committed to reducing the country’s budget deficits. Motivated by this goal, the government implemented many policy reforms that were aimed at reducing government spending to improve the prospects of realizing a favorable balance sheet. True to the conviction of the Canadian government, the country was able to transform its budgetary deficit to a surplus. The government achieved this goal by embarking on a rigorous campaign to sensitize the Canadian public about the debt situation. This strategy was aimed at achieving public buy-in. Canada’s debt situation was completely solved after these interventions. Wright (2010) explains that,

“Following a peak deficit of $42 billion in fiscal 1993–1994, the administration managed to reverse the deficit and produce a surplus by 1997–1998 and sustain the surplus over the following two years before posting a historical record of $17.1 billion in budgetary surplus in fiscal 2000–2001” (p. 21).

Since the budgetary surpluses were realized, the Canadian government has been able to maintain budgetary surpluses for several years preceding the 2007 crisis. Occasionally, Canada achieved high budgetary surplus while other G7 countries experienced budgetary deficits. Considering the improvement of the Canadian balance of payment, Canada was rated as the best performing country in the G7 alliance after it posted several budgetary surpluses since the 1960s (Wright, 2010, p. 48). Canada now holds the record as the only G7 country that has reported ten consecutive budgetary surpluses since the sixties. This good record was only interrupted by the political rhetoric that characterized the 2008/2009 period when Canada experienced a budgetary deficit.

However, the journey to achieving a budgetary surplus was not smooth for Canada because the government embarked on implementing significant tax cuts. For example, in 2001, the government implemented a $58 billion tax cut which prompted provincial governments to implement personal income and corporate tax cuts as well (Wright, 2010, p. 48). The fiscal turnaround in Canada was, therefore, achieved in this manner but a significant reduction in government spending also accounted for a significant proportion of the country’s budgetary turn around. The previous strategy adopted by the previous government was to increase the government’s spending to reduce the unemployment rate.

As fate would have it, this strategy proved to be disastrous for the Canadian economy because the government accumulated a lot of debt that saw the debt to GDP ratio increase to 60% (Wright, 2010). However, the goal of reducing unemployment rates was realized since the government reduced the unemployment rate from a high of 11% to 6%. The increase of debt ratios is an example of the failure of free market doctrines that characterize economic doctrines in most western countries, including the US.

The failure of free market doctrines informed Canada’s reaction to the 2007 crisis. However, other western nations like the US still hold on to these doctrines. This ideology informs the declaration by the US government that it was going to introduce different economic stimulus packages to revamp its economy again. Canada does not subscribe to this doctrine.

Canada’s response to the crisis provides a good ground for analyzing the difference between its economic policies and those of other states. However, it should be understood that the economic policies adopted by the Canadian government does not completely explain the economic predicament of the country. Indeed, it is very difficult to explain the country’s success in the 2007 GFC when we only analyze the policy-aspect of the crisis. The 2007 GFC among other crises such as the Greece crisis and the US mortgage market collapse cannot be realized within one political term. Therefore, such crises can only be explained from a long-term insight into the economic underpinnings of the specific society. This analysis prompts an investigation into the nature of Canada’s banking system.

Canadian Banking System

Performance

The Canadian banking system has been at the epicenter of Canada’s economy. Among other sectors of the country’s economy, the Canadian government has greatly relied on its banking system to stabilize the national economy. This focus is necessitated by the importance of maintaining a sound banking system in not only Canada but also elsewhere around the world. Therefore, the focus on the banking system is not only exclusive to Canada.

The notion that Canada has fared better than other economies during the 2007 GFC is a commonly accepted fact. Excerpts from Department of Finance Canada (2011) explain that as other industrialized nations struggled to keep their economies from succumbing to the 2007 GFC, Canada was in the middle of an economic recovery after it experienced one of its mildest recessions in years.

Alongside Canada’s sterling banking performance has been its growth in GDP. For the three years preceding the year 2010, Canada has constantly been experiencing GDP growths of 3% to 5% (Department of Finance Canada, 2011). The situation was, however, bleak for America because it posted GDP contractions of between -0.6% to -8.4% throughout two quarters of 2008, and two quarters of 2009 (from the third quarter of 2008 till second quarter of 2009). The following table shows these GDP contractions.

Nonetheless, like America, Europe experienced the same GDP contractions. Unemployment rates in Canada, occasioned by the 2007 GFC, were also considerably low when compared to other industrialized nations. As at 2011, it was reported that the Canadian economy recouped all the job losses and was now posting significant increases in job opportunities. Comparing the current unemployment rates in Canada and the US, we can see that Canada posts lower unemployment rates (of 7%) while the US posts figures of 9% (Department of Finance Canada, 2011).

Recent statistics also show that the optimism among Canadian firms to hire people is considerably high. Currently, there are very many optimistic firms, which intend to undertake more recruitment in the coming years. In fact, current statistics show that about a quarter of all Canadian firms are now reporting labor shortages of about 10% of the operating capacity (Department of Finance Canada, 2011). The level of investor spending is also expected to rise in the coming years, owing to the tremendous optimism projected by Canadian executives.

Investor spending is an important indicator of an economy’s performance, but it is often overshadowed by the emphasis on consumer spending. The great prospects surrounding the future of the Canadian economy and its banking system has led to a surge in the value of the country’s currency. This is a record high for Canada’s economy.

Structure, Culture and Regulation

Changes to the structure, culture and regulations of Canada’s banking system started during the early thirties. Even though there was no central Bank in the early thirties, it is observed that no Canadian bank failed during the great depression. However, in 1935, the central bank was established as a lender of last resort (Miles, 2004, p. 13). Canadian banks could, therefore, borrow funds from the institution but subject to approval by the treasury board. Miles (2004) explains that the country’s central bank oversaw the growth of a few major banking institutions. As will be seen in subsequent sections of this paper, the small number of national banks contributed to Canada’s stability during the GFC because these banks had a nationwide effect on the country’s financial system.

However, since the 1980s, Canada has done several reviews and policy changes on its structure, culture and regulatory environment (Miles, 2004). Previously, the Canadian financial system was operating in an environment characterized by delineated financial pillars. These pillars were, however, reviewed by the government through policy improvements that allowed Canadian banks to acquire investments companies. Subsequent legislative changes saw the federal government allowing the ownership of insurance firms and trusts by banks. These policy reviews saw the growth of large financial institutions. Consequently, the influence of banks on Canada’s financial system peaked.

In the same way, the federal dominance on Canada’s financial system peaked because banks were mainly categorized under the control of the federal government. The strong influence of the federal government rested on political, supervisory and regulatory powers. Since these changes were adopted, there has been no collapse of the Canadian banking system, as was witnessed in the 80s. In the 80s, the Canadian policy framework was inherently weak. The ABCP (Asset-Backed Commercial Paper) crisis is one such manifestation of this weakness because it shows the economic losses that were realized when Canada’s economic policies were not right.

Despite the role played by a strong, cohesive policy network, we can see that the integrative framework adopted by the Canadian financial market is part of the country’s business culture. Evidently, we can also establish that the integrative policy framework seen in Canada is part of a governmental attitude cemented by conservative policy makers. This attitude forms part of the Canadian business culture.

Comparatively, the US financial market plays host to a subsystem of diverse coalitions, which are controlled by many players as part of its competitive spirit – also forming part of the US business culture. As will be explained in this paper, the different players controlling the US financial systems have divergent views, which clash with one another. These uncoordinated market operations provided a fertile ground for the start and spread of the 2007 financial crisis. Unfortunately, Johnson (2011) explains that this situation may not change in the near future.

Nonetheless the Canadian policy changes that occurred in the 80s, stabilized the Canadian banking system, but most importantly, it established an oligopolistic banking system (Miles, 2004). This environment is in sharp contrast to the US banking system, which is composed of thousands of banks. Throughout the 90s, there was further debate initiated by Canada’s policy makers regarding the country’s financial sector policy. This debate birthed bill C8 in 2001 (Miles, 2004). This bill mainly sought to facilitate the competitive environment in the country’s financial system, but at the same time, uphold consumer protection policies. During the repeal of Canada’s financial policies, there was a push by four of Canada’s largest banks – Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce and Toronto Dominion, Royal Bank and the Bank of Montreal – to merge.

These banks claimed that they were missing the existent opportunities for operating in large scale. Moreover, they claimed that through the merger, they would be able to serve their customers better. The year 1998 hosted most of the debate regarding this merger. However, contrary to the expectations of these banks, the proposal to merge was denied by the Canadian government (Miles, 2004). There was a general mistrust among the Canadian public regarding the intended merger, but Canada’s policy makers were mainly concerned about the future of Canada’s marketplace. The biggest concern was the reduction in the number of major banks from five to three.

As fate would have it, the denial by the Canadian government to grant the merger application protected the country from the 2007 financial crisis. Bill C8, which was a product of this debate, was intended to serve many purposes. It also created the Consumer Financial Agency of Canada (FCAC) which served to protect the interest of the Canadian public (Miles, 2004). However, through the public debate that characterized most of the late 80s and 90s period, most Canadian banks are now not willing to merge. Existent regulations do not also allow for the sale of insurance throughout any of the bank branches and or the leasing of vehicles (as was demanded by many of Canada’s major banks).

The policy changes adopted by the Canadian banking system have mainly been informed by the changing financial environment, which is especially driven by globalization forces. However, though Canada acknowledges that it cannot operate without factoring the global forces that characterize its international operations, the country still protects itself from the negative effects of external financial forces through its policy reviews. One such policy area that the Canadian government has implemented to mitigate the negative effects of external financial forces is in sub-jurisdiction. This policy structure among other reasons has prompted many experts to declare that the Canadian financial system is among the best functional systems in the world.

Alongside this endorsement is a double A2 rating which has been given to Canada’s banking sector by the credit-rating agency (Denette, 2012). The functionality of Canada’s banks is also affirmed through its safety and soundness. Basically, Denette (2012) explains that Canada’s banking system is properly managed, thereby giving its investors a safe haven for their investments. A lot of praise has been given to the country’s federal government for this acclamation. In fact, the double A2 rating of the bank is higher than most banks in not only America but Europe and Asia as well (Denette, 2012).

Observers also agree that considering Canada’s financial structure, Canadian banks are too big to fail, yet according to global standards, Canada’s banks are still relatively small (Stern, 2004). Miles (2004) explains that most activities of Canada’s banks are mainly centered in the US. Miles (2004) also adds that the Far East also enjoys considerable trade with some of Canada’s largest banks. Considering the current financial environment in Canada, Miles (2004) observes that there is a strong degree of equilibrium, which prevents many of the actors from demanding more reforms to the existing system.

On the same token, Miles (2004) explains that the policy framework for Canada’s financial system is relatively small when compared to the US and, therefore, the cohesiveness of the system is much stronger than the US. The size of the policy network should, however, not be assumed to be like a policy community, but observers note that the Canadian policy network shares the same attributes with the latter. Before the policy reviews undertaken in the late 80s and early 90s, Canada’s policy network was comprised of “the Canadian Department of Finance, the Bank of Canada, and the Office of the Inspector General of Banks – OSFI’s precursor, the Canadian Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC), and the Canadian Bankers Association, with potentially a few big banks” (Miles, 2004, p. 43).

It is reported that during the period where the above institutions characterized Canada’s policy framework, the policy formulation process was largely insulated. However, with the policy changes that happened in the 90s, there was a subsequent change in the framework of policy implementation. The most significant changes to the policy framework was the addition of new actors (Miles, 2004, p. 23). The addition of the new entrants into Canada’s policy framework heralded the new policy framework birthed from the dismantling of initial policy pillars. Among other institutions that were on the network periphery were “Foreign financial institutions, provincial regulators, and the Investment Dealers Association, now known as the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada, a self-regulatory organization”2 (Miles, 2004, p. 3).

With the introduction of Bill C8 amendments, there has been a rapid expansion of the policy network, but throughout the years, there has been no significant change in the way the network operates. Notably, the dominance of Canada’s federal government has not changed over the years, because the federal government, which occasionally acts as the final arbiter, oversees the network’s operations. Key departments within the federal government such as “the Department of Finance, the Bank of Canada, OSFI, CDIC, and the FCAC” (Miles, 2004, p. 4) mainly undertake the control of the federal government. The main tasks of these departments are to ensure the policy network works in cohesion. Another task given to these departments is to ensure that there is an open line of communication between players in the policy network and the government.

Comprehensively, we can see that Canada’s success in the 2007 GFC can be attributed to several banking practices, which have been institutionalized over the decades to protect the country’s economy from external shocks. From the findings of this paper, we can also establish that Canada’s banking institutions are relatively strong compared to the US. Their strength can be attributed to the oligopolistic nature of Canada’s banking system. The business practices adopted by these Canadian banks are also accountable for the success of the country’s banking system in wading through the 2007 GFC. In addition, these banks have been operating under prudent managerial policies, which saw them avoid the pitfalls of the sub-prime mortgage market.

Moreover, through the same policies, these Canadian banks managed to avoid mortgage-backed securities, which accounted for the downfall of the US mortgage market. Their market capitalization, stability and security have also been well entrenched in the country’s financial system. These attributes prompted the country’s banks to sail through the 2007 without getting any government bailouts. When the GFC became widespread and most Canadian banks felt the pressure of the crisis, the Canadian government worked to support the country’s banking institutions to improve their liquidity. This move improved the country’s position to fight the crisis.

The government’s support of its banking institutions also highlights the close relationship that Canada’s monetary system shares with the government. Clearly, there is a mutual relationship existing between the country’s financial institutions and Ottawa. Open lines of communication between the government and existing banking institutions characterize this relationship. Therefore, unlike America, Canada’s government is well versed with the activities and problems ailing the country’s financial institutions (Freeland, 2010).

The situation is very different from the US because Washington does not seem to understand what Wall Street is doing and the reverse is also true because Wall Street’s policies seem to contravene Washington’s. The Canadian situation is, however, unique to most economies because the government does not own any of the country’s commercial banks, yet it enjoys a good relationship with most of them. Through government intervention in improving liquidity, it was evident that throughout the 2007 financial crisis, Canada’s businesses and consumers had adequate access to credit.

Nonetheless, despite the functional framework for the policy network, Miles (2004) explains that the main weakness of this network is the lack of a common body that ensures the financial system remains stable. In reference to this concern, there have been previous concerns expressed by some of Canada’s previous governors about the limited strength that the Bank of Canada has in mitigating a financial crisis. Regardless of this limitation, the international monetary fund has cited Canada’s financial system to be among the most unified and effective monetary systems in the world (Miles, 2004).

Main Strengths and Advantages

Canada’s reaction to the 2007 global financial crisis was unique from the start of the crisis. Many observers attribute the country’s resilience to the crisis as part of the advantages enjoyed from the strong regulatory framework of the Canadian economy (Department of Finance Canada, 2011). Other observers note that the good banking management standards adopted in the country was also part of the reason for the country’s resilience to deal with the GFC. However, a recent report tabled at Rutgers University showed that the difference in monetary policy was the main reason for Canada’s success in the GFC (Department of Finance Canada, 2011).

At the same conference, the difference between America and Canada’s housing market was also identified as another factor that contributed to Canada’s resilience in the GFC. Through these differences, it is observed that Canada’s financial institutions were mainly focused on supporting quality mortgages as opposed to any type of mortgage. Through the same analysis, it is observed that Canada’s financial institutions refrained from entering the subprime mortgage market. These characteristics accounted for the low level of loan defaults in Canada and the high levels of mortgage defaults in America.

Furthermore, in reference to the low levels of mortgage defaults, it is reported that Canadians who could not manage to come up with 20% down payment for mortgages had to purchase insurance to guarantee that they would not default on their financial agreements. Through such policy provisions, it is reported that Canada’s housing market managed to perform relatively well compared to America’s mortgage market.

Department of Finance Canada (2011) explains that the Canadian financial system generally relies on a very prudent framework for evaluating risk and evidently, this culture makes them highly risk averse. Canada’s position prior to the GFC is also seen by the Department of Finance Canada (2011) as another area of strength that enabled the country’s economy to withstand the storm of the GFC because investors lost hope in other western economies and turned to Canada because its economy was more stable.

The role of the Canadian government in averting the impact of the 2007 GFC is also another advantage of the Canadian economy as it strived to avoid the effects of the credit crunch. As opposed to its southern counterpart (US), the Canadian government was proactive in its approach to the GFC. For example, the support for low interest rate by the Bank of Canada stimulated economic development.

The increased purchase of mortgage bonds by the Canadian government, which amounted to about $125 billion, also improved the ability of its banks to lend to the economy (Department of Finance Canada, 2011). The purchase of mortgage bonds was done through the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program (IMPP) (CMHC, 2012, p. 2). This program was set up by the Canadian government to handle liquidity problems which were occasioned by the lack of credit (which originated from America and spread throughout Europe and other parts of the world) (CMHC, 2012, p. 2).

As explained in earlier sections of this report, the Canadian government embarked on this strategy to stabilize its housing market, and by extension its overall economy. CMHC (2012) explains that “The IMPP authorized CMHC, on behalf of the Government of Canada, to purchase up to $125 billion in National Housing Act Mortgage-Backed Securities from Canadian financial institutions, giving them access to longer-term funds for lending to consumers, homebuyers and businesses”3 (p. 3).

This government scheme proved beneficial to the economy and borrowers because it improved mortgage securitization in Canada. CMHC (2012) explains that this strategy was simple and high quality because it consistently provided credit to customers so that they can participate in the mortgage market. Smaller lenders have benefitted the most from this scheme because it has provided them with the opportunity to compete with larger institutions in the mortgage market.

Consequently, through the healthy mortgage market, there has subsequently been another healthy competition among lenders in the same industry. This healthy competition has managed to keep the interest rates low and stable. Similarly, innovation within this financial sector has been improved and more consumers have had an expanding choice of products within the market. Increased innovation and an expanding product array have also facilitated a healthy price competition which has also stabilized further the market (CMHC, 2012, p. 2).

The administrative support given by Canada’s central government to the leading banking institutions to manage the 2007 GFC was also another advantage that supported Canada’s resilience to overcome the GFC. This legislative support was accorded through the repeal of the Canadian banking act. In addition to this legislative support, Department of Finance Canada (2011) explains that “The Canadian government also promised to strengthen the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI), the federal financial services sector supervisor and regulator” (p. 6).

The Canadian government accorded this legislative support after the above institutions were accused of not stopping the ABCP (Asset Backed Commercial Paper) crisis that hit Canada a few years back. The Canadian government also implemented new rules to regulate principle-protected notes and any insurance that was set to protect investors from losing their money. Alongside this policy reform was the push by Canada’s federal government to establish a National securities commission to protect investors and customers against market uncertainties. From the above governmental interventions, clearly, the financial system was under control. The same cannot be said for the US financial system.

The cohesiveness that Canada’s monetary system has is also another strength cited by the Department of Finance Canada (2011) that contributed to its resilience in the 2007 GFC. The cohesiveness of the country’s financial system has already been cited in earlier sections of this paper as a product of the policy reforms undertaken in the late 80s and early 90s. However, this area of study highlights one of America’s main weaknesses in mitigating the effects of the 2007 GFC. There is a sheer lack of cohesion between the US monetary system and the government. More so, there is a strong discord between the activities of Wall Street and Washington.

The difference between the two centers of power can also be seen through the discord between regulatory and supervisory activities in the US financial system. Different financial firms used the discord between regulatory and supervisory services to pick selectively different regulators and play one against the other. Through this understanding, there was a plot of ineffectiveness in regulatory services, but most unfortunately, these regulatory institutions were severely under-resourced. Again, through the discord between regulatory institutions and their subjects, the relationship between the two parties was largely confrontational as many episodes of negotiations were largely done through lawyers.

Canada’s proactive initiatives on the global financial front have also been a strong advantage for the country’s monetary system because the country has been able to be abreast with the activities of the international financial system, and thereby adjusting accordingly. Practically, Canada has been an active member of the G8 and G20 summits where it has championed different reform initiatives in the global financial system (Department of Finance Canada, 2011). For example, regarding the intense debate about whether banks should be punished for creating bailout funds, Canada proposed that banks should be allowed to have a contingency fund as opposed to the former (bailout funds).

For a long time, government bailouts (in times of economic crises) have been debated by many economists. Many politicians often express the view that bailing financially trodden companies can easily save such entities from eminent collapse (Roche, 2010). This is the same ideology that informed the decision by most western government to allocate billions of dollars in government bailout funds. According to Roche (2010) this ideology is misleading because government spending does not work like consumer spending. The main difference between government spending and other types of spending is that governments do not profit from spending. Therefore, when government bailouts are approved, it is virtually impossible to make profits from such undertakings (and therefore, it does not make economic sense to give corporations money while no returns can be derived from them). Essentially, governments do not work to make profits.

In this regard, it is very difficult to ascertain if alternative interventions (that do not include government bailouts) could have worked in the 2007 GFC. Roche (2010) explains that the entire notion that offering government bailouts can effectively save a downtrodden financial system is misleading because in his view, government bailouts increase moral hazards, inflationary pressures, and mal investments. Similarly, Roche (2010) also disagrees with the opinion that government bailouts can make people rich.

He explains that government bailouts do not make people rich; in any case, these bailouts make people poorer when inflation and high taxes take effect. Similarly, when different governments bailout corporations, it does not mean that these governments have (had) more money. Therefore, the notion that people (and by extension the government) become rich is misleading. Through the above understanding, many people would often wonder who gains from government bailouts.

To answer this question, Roche (2010) explains that the entire notion of government bailouts is very interesting and ironic. Referring to the 2007 GFC, Roche (2010) explains that bankers are the only people who gained from the government bailouts. This analysis is very ironic because it ultimately turns out that the people who caused the global financial crisis are the same people who benefit from government bailouts. This is the same principle that has guided many countries to oppose the entire idea of government bailouts. Similarly, such sentiments characterize Canada’s reservations about government bailouts.