Risk Governance Definitions

A risk, in general terms, connotes the uncertainty or unexpected ‘adverse’ outcome of a situation or activity. The scholarly literature on risk governance explains the processes and frameworks for managing risks based on diverse definitions of risk governance. Klinke and Renn (2012) define risk governance as a comprehensive risk-handling process for addressing the “complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity” aspects of risk (p. 274). It entails an evaluation of the totality of regulations, processes, and systems involved in the risk data collection, analysis, and risk-based decision-making. Therefore, it extends beyond the traditional risk analysis to include normative principles on how public and private actors can manage risks.

Renn, Klinke, and van Asselt’s (2011) definition of risk governance follows a technocratic approach. They define it as the organisational structure and policymaking process that guide or control the regulation or mitigation of risks at the group, societal, national, or global level (Renn, Klinke & van Asselt 2011). This definition is based on the shift from centralised decision-making to multi-level public administration that characterises modern governments. In another article, van Asselt and Renn (2011), extending on the International Risk Governance Council’s [IRGC] definition, describe risk governance as the application of core principles/concepts of governance in risk-based decision-making extending beyond formal (probabilistic and regulatory models) to include informal processes. The definition is informed by the inadequacies of risk probability models in managing public risks. It includes formal and informal systems for dealing with complex, uncertain, and ambiguous risks. In this article, the concept of governance primarily relates to policy development by government actors. However, since various players are involved in the management of society, including non-governmental organisations and the private sector, the definition has been expanded to include a diversity of actors/roles.

The phrase risk governance is utilised in a prescriptive and a descriptive context. Decisions about risks involve diverse players, regulations, political systems, and organisational structures – aspects pertaining to governance. Risk decisions are the outcome of the interaction between many players. From a governance perspective, the societal factors that precipitate outcomes characterised as risks need to be analysed for effective mitigation. For Flemig, Osborne, and Kinder (2015), risk governance is both a normative and prescriptive process. They define it as a hybrid of “an analytical frame and a normative model” that guide risk decisions (Flemig, Osborne & Kinder 2015, p. 16). This decision-based risk governance differs from the technocratic approach in the sense that it assigns the decision-making role entirely to politicians.

Brown and Osborne’s (2013) definition of risk governance follows a different approach. They define risk governance as transparent engagement with the “nature, perceptions, and contested benefits of a risk” in complex situations (Brown & Osborne 2013, p. 199). This means that all relevant stakeholders in the public service are involved in the decision-making process. This transparent approach has been adopted in the modern public sector to enhance accountability. In addition to the inclusive decision-making process, the risk environment is characterised by regulations and best practices to enhance accountability in the public sector. Therefore, Brown and Osborne’s (2013) definition fits within the transparent risk management approach adopted in democratic systems.

The Concept of Risk Governance and Purpose

Various epistemological premises and ideas contributed to the development of risk governance as a concept. In contrast, the positivistic/realist view relies on the assumption that risk is assessed based on some ‘real’ standard, while the social constructivist approach considers risk a “social process”, not as a distinct entity (Renn 2011, p. 71). These ideas helped advance the principles and frameworks for managing contemporary risks. The conceptual use of the term ‘risk governance’ emerged in recent literature exploring policy development in the public/private sectors (van Asselt & Renn 2011). It is used within the context of public/private governance or development that has roots in the political science field. In this context, ‘governance’ stresses the role of non-state actors in the management and organisation of societal issues (van Asselt & Renn 2011). This approach challenges the classical policy perspectives that followed a hierarchical power model centred on the government.

In the governance view, collective binding decisions are produced in “complex multi-actor networks and processes” (Jonsson 2011, p. 126). This means that multiple social actors are involved in governance. Besides the state, the other social actors include nongovernmental organisations, private institutions, expert groups, etc. In this regard, the power/capacity to organise and manage society is shared among the different actors. Governance can be considered a descriptive and prescriptive term. The descriptive sense of governance relates to the complex interplays between various social actors, structures, and processes (Jonsson 2011). In contrast, the prescriptive definition relates to the model/framework for the management of societal issues. The normative use of governance emphasises transparency, involvement, and accountability.

The normative-descriptive ideas also apply to risk governance. The word ‘governance’ is utilised in “a normative and descriptive sense” (van Asselt & Renn 2011). The argument here is that while the regulation/management of simple or systemic risk problems follows the governance framework, risk decisions emanate from interactions between stakeholder groups. The ‘governance’ view gives a framework for examining and describing the factors precipitating risks. However, the unpredictable nature of risks calls for multi-stakeholder collaboration to address and manage them adequately. In the collaborative frameworks, new risk management principles and approaches are proposed – in line with the prescriptive/normative perspective (Renn 2011). Therefore, risk governance is a blend of an analytical framework and prescriptive exemplars.

The usage of the term ‘risk governance’ has its roots in the lessons learnt from the TRUSTNET undertaking, which developed a model that included collaborative processes in decision-making (Renn 2011). TRUSTNET was a European Union interdisciplinary network established to develop the criteria for determining best practices in the governance of hazards. It comprised 80 experts drawn from regulatory agencies in industrial and medical fields across Europe. The network developed the concept of risk governance and the first model. Later, this notion was used in literature as an alternative paradigm to the traditional concepts of risk analysis and management by advocating for multi-stakeholder roles, processes, and systems (van Asselt & Renn 2011). However, risk governance was originally used to mean an all-encompassing system of “risk identification, assessment, management, and communication” (van Asselt & Renn 2011, p. 433). This view is consistent with the IRGC’s definition of the notion of risk governance. The IRGC (2015) incorporates the governance principles of “transparency, effectiveness, accountability, equity, and fairness” into its definition of governance framework (p. 12). The aim is to create effective collective actions to mitigate the effects of emerging risks.

The purpose of sound risk governance is to reduce the unequal risk distribution between different public/private institutions or social groups through multi-actor processes. A risk governance practice also creates consistent and uniform approaches for similar risk assessment and management (Renn 2011). Unlike the traditional approach of risk analysis that focuses on high-profile risks, risk governance gives adequate consideration of high-probability risks irrespective of their profiles. It also involves risk trade-offs through effective regulations and policies. The approach also takes into account public perceptions, resulting in high public trust in the system.

Risk Governance Frameworks

The risk governance frameworks provide an approach for the analysis and management of risks within the public service or the private sector. Brown and Osborne (2013) suggest a risk governance model for managing risks related to innovation in the public sector. The framework links three management approaches and three innovation types (Figure 1). The first type is evolutionary innovation, whereby institutions utilise new “skills or capacities” to meet specific user needs (Bernado 2016, p. 14). The second type is expansionary innovation, whereby the current skills/capabilities are used to meet expanding user needs. The last one is total innovation, in which new capabilities/skills are developed to address new user needs (Brown & Osborne 2013). The authors offer three risk governance approaches, namely, technocratic, decisionistic, and transparent methodologies. The technocratic model is only applicable in evolutionary innovation. In contrast, the decisionistic model provides a framework for evolutionary and expansionary innovation. The transparent risk governance model can accommodate all three types of innovation.

Figure 1: Risk Governance Framework for Public Service Innovation

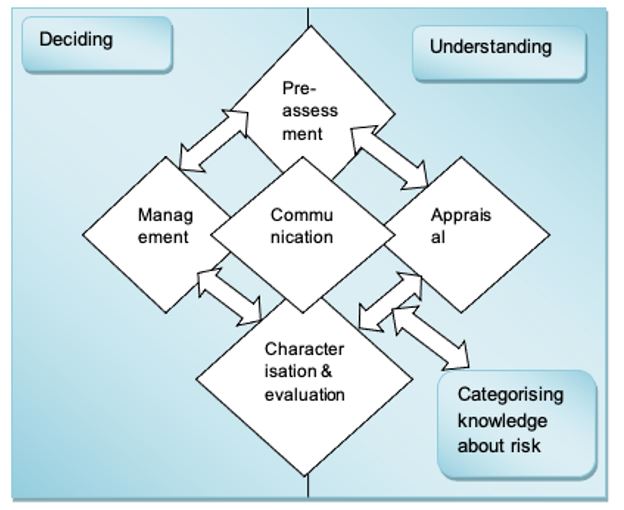

Another risk governance framework is the IRGC’s model that consists of five related phases. The phases include pre-assessment, appraisal, characterisation and evaluation, management, and communication (Figure 2).

The model separates risk analysis from the understanding of risks. Risk appraisal is essential in understanding the nature of risks. In contrast, the implementation of risk decisions requires risk management. The framework begins with pre-assessment, whereby the risk is defined to facilitate its appraisal. The pre-assessment phase involves a set of questions that give the baseline data for risk assessment and mitigation. More importantly, it reveals the factors that precipitate the risk and the associated opportunities (Bernado 2016). It also brings out the risk indicators and patterns that help inform the risk management approach. The governance shortfalls that occur during this phase include failure to detect risk signals, perceive their scope, and frame it appropriately.

The risk appraisal phase is where facts and assumptions are developed to make a determination if a situation portends a risk and how it should be handled. The appraisal involves scientific approaches, including estimating the probability of occurrence and risk-benefit analysis based on stakeholder concerns (Bernado 2016). The process ensures that policymakers consider stakeholder concerns and interests when making decisions. The next phase – characterisation and evaluation – involves the consideration of societal values in decisions related to the acceptability or tolerability of the risk. At this stage, risk mitigation measures are identified for risks considered acceptable or tolerable (van Asselt & Renn 2011). However, if the risk is intolerable, the initiative is halted. The failure to address the issue of inclusivity, transparency, and societal values/needs, and timeframes precipitates risk governance problems.

The fourth phase is risk management. It entails the development and adoption of strategies or activities that help mitigate, avoid, or tolerate the identified risk. In this stage, multiple options are developed, and the best one is selected for implementation. The risk management process entails the “generation, evaluation, and selection” of the best risk mitigation strategy (van Asselt & Renn 2011, p. 445). It also entails evaluating the potential impacts of the selected risk mitigation option. The final phase of the IRGC framework is the communication of the risk management decision. Effective communication helps create awareness among stakeholders. It also enables them to understand the stakeholder role in risk governance (van Asselt & Renn 2011). The communication should inform the stakeholders/actors about their specific roles in managing the risk.

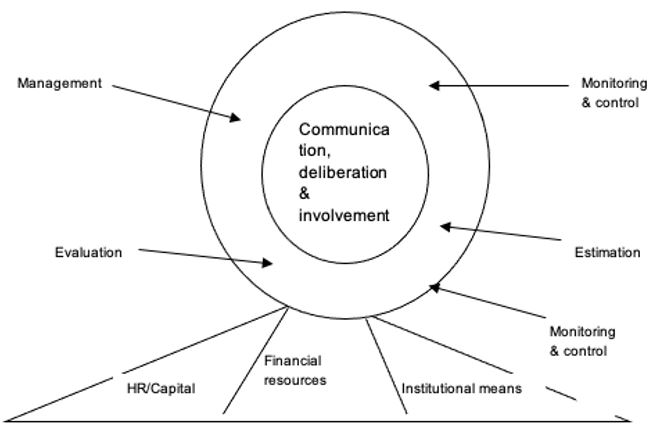

Renn, Klinke, and van Asselt (2011) propose a modified IRGC framework that includes the normative and descriptive aspects of risk governance. The proposed model comprises five stages, i.e., “pre-estimation, interdisciplinary risk estimation, risk characterisation, risk evaluation, and risk management” (p. 237). The modified framework is illustrated in Figure 3 below. The pre-estimation stage involves the testing of multiple problems as possible risks. It entails an exploration of societal/community and political agencies and the public to identify factors ‘framed’ as risks. The screening also explores the culturally constructed risk candidates. Therefore, the pre-estimation stage is a multi-stakeholder process that brings together government agencies, industry actors, consumers, and various interest groups.

The second stage, risk estimation, entails the scientific evaluation of risks through risk assessment and concern (societal issues) assessment (Renn 2011). Various approaches can be used in risk estimation. Examples include the probability of occurrence, the extent of damage, ubiquity, reversibility, etc. The third step, risk evaluation, involves the quantification of the societal effects of risk and its probability of occurrence. The risk profiles are evaluated based on their level of acceptability (Renn 2011). Low-risk situations or activities are considered highly acceptable. Risk management is applied to risks considered tolerable. It entails a suite of mitigation measures to reduce the adverse consequences of a risk. Risk communication/participation entails educating the masses through interactions to disseminate information related to the risks (Renn 2011). The aim is to build trust relationships in risk management through multi-actor inclusion.

Risk Governance Phases and their Components

The cyclic process of risk governance occurs in a logical sequence of five phases: pre-assessment, appraisal, characterisation and evaluation, risk management, and communication (Roeser et al., 2012). The individual phases and their specific components are described below.

Pre-assessment Phase

The pre-assessment phase is the screening stage of the risk governance process. Here, the actors consider diverse issues related to a specific risk. In addition, the different stakeholders review the risk indicators and practices at this stage. The main components of the pre-assessment phase include “problem framing, early warning, pre-screening, and the determination of scientific conventions” (Roeser et al., 2012, p. 51). The purpose of risk framing is to explore the multi-actor perspectives and establish a common understanding of the risk issues. Based on an agreed risk frame, the signals or indicators of the risk/problem can be monitored.

Early warning helps identify indicators that confirm the existence of a risk. It entails an exploration of institutional capabilities for monitoring early warning signs of risk within an organisation (Rossignol, Delvenne & Turcanu 2015). Pre-screening encompasses preliminary analysis of risk candidates and prioritising them based on probabilistic models. It also entails identifying the appropriate evaluation and management route for each risk candidate. It is followed by a determination of the main “assumptions, conventions, and procedural rules” required for the assessment of the risk (Rossignol, Delvenne & Turcanu 2015, p. 137). The stakeholder emotions related to the risk issues are also considered in this step.

Risk Appraisal Phase

The purpose of risk appraisal is to create societal standards or scientific thresholds for risk. It also gives a knowledge base for identifying appropriate risk mitigation or containment approach. Its main components include risk assessment and concern assessment (Roeser et al., 2012). A risk assessment identifies the cause-effect relationship of risk as well as its probability of happening. It may involve risk identification and evaluation to estimate its severity. The objective of concern assessment is to explore the stakeholder’s anxieties and fears related to the risk (Roeser et al., 2012). It also illuminates the socioeconomic impacts of a risk-based on stakeholder perceptions.

Risk Characterisation/Evaluation Phase

This phase involves estimating how acceptable or tolerable a risk is to the stakeholders. Therefore, the two components of this phase are risk acceptability and tolerability. A risk problem considered acceptable has lower adverse impacts on health/environment than a highly unacceptable one (Karlsson, Gilek & Udovyk 2011). This means that the risk does not require mitigation efforts. On the other hand, a tolerable risk has significant trade-offs between benefits and adverse effects. As a result, specific mitigation measures are adopted to reduce the negative effects. Characterisation helps generate an evidence base from the outcome of the risk appraisal phase. In contrast, evaluation involves the consideration of extraneous factors relevant to the risk.

Risk Management

The risk management phase involves the development and application of mitigation actions geared towards averting, diminishing, or retaining risks. It proceeds through a six-step process that culminates in an optimal option for risk management. The first component involves the formulation of an array of options for addressing the risk (Roeser et al., 2012). This initial step relies on the acceptability-reliability considerations relevant to the specific risk. The next step involves the evaluation of the options based on specified criteria, e.g., sustainability or cost-effectiveness (Karlsson, Gilek & Udovyk 2011). Thirdly, a value judgment based on the weights assigned to each criterion is applied to the options. Subsequently, the best option(s) is chosen for further consideration in the fourth step. The fourth and fifth steps cover the execution of the best risk management strategy and monitoring and evaluation of its impact on the reversibility of the risk.

Communication Phase

Risk communication is an ongoing activity during the risk governance process. Its aim is to enlighten non-participating stakeholders regarding the risk decisions emanating from the preceding phases (Roeser et al., 2012). Additionally, risk communication helps support informed choices by stakeholders based on the consideration of societal/individual interests, fears, values, and resources (Roeser et al., 2012). As a result, conflicting perspectives are managed to arrive at a consensus risk management strategy for the institution. Effective communication is also required between policymakers and experts/assessors to avoid bottlenecks related to communication lapses.

Risk Governance in Public and Government Sector and State-owned Enterprises

Risk governance approaches differ between governments and public policy domains. In the UK, the dominant historical feature of risk governance was decision-making processes founded on scientific research, economics, and technical know-how (Rothstein & Downer 2012). As such, public risks were managed through policies, e.g., the road safety policy, informed by distinct philosophical and practice foundations. More recently, risk analysis tools and principles have been adopted in risk governance initiatives in the public sector with the aim of improving risk tolerability to nurture creativity. Risk analysis based on probability models is used by the central government on a regular basis to inform the public about issues, such as the possibility of floods or depressed GDP growth. Moreover, public policy domains related to “service delivery, inspection, and enforcement” in the social service sector use risk-based strategies for prioritisation and regulation of activities (Rothstein & Downer 2012, p. 791). The same approaches are entrenched in state-owned enterprises.

Certain structural reforms precipitated the current risk governance practices in the UK. First, the occurrence of high-profile crises, e.g., disastrous floods, increased government efforts in risk analysis. As a result, the National Risk Register was created to help in the framing and evaluating public risks based on “probability-x-impact frameworks” (Lodge & Wegrich 2011, p. 94). Second, risk governance is adopted in regulatory interventions, inspections, and enforcement. The rationale is to provide checks and balances for the bureaucratic systems to spur entrepreneurial growth in the public sector. Third, accountability systems have been implemented to create transparency and minimise the risk of failure. Managerial approaches, e.g., the New Public Management system, aimed at improving decision-making processes to reduce the risk of failure (Lodge & Wegrich 2011). The approaches have made civil servants accountable for their governance/managerial actions or inactions.

In addition, the UK’s bureaucratic and legal systems are a source of accountability pressure for civil servants. They have to consider the expected trade-offs for a risk/failure to be defensible before the public. However, risk-based rationalisations tend to conflict with professional principles in certain public sectors (Lodge & Wegrich 2011). For instance, risk-based management of the medical practice may conflict with the professionalism enshrined in the Hippocratic Oath (Lodge & Wegrich 2011). In addition, predicted risk-based rationalisations have gained use in the legal environment, with attorneys framing risks based on costs and the probability of occurrence (Rothstein & Downer 2012).

Other comparable jurisdictions use different risk governance approaches from that of the UK. The French practice is founded in a technocratic (elitist) system and various institutional/constitutional principles that stand in the way of institutionalised risk-based governance. These philosophies include the government commitment to public security, the establishment of public order, equal rights principle, and general interest maxim (Lofstedt 2011). Public officials must defend these paternalistic principles. However, the entrenched institutional cultures conflict with open and inclusive decision-making systems that are crucial in risk-based governance. The French government deals with this limitation through opacity, failure acknowledgement, and reactive crisis management (Lofstedt 2011). As a result, public officials tend to be risk-averse and precautionary as opposed to being receptive to risk tolerance/acceptability principles.

In contrast, in Germany, constitutional provisions limit the development of a risk governance culture in the government and state-owned agencies. In particular, the ‘Schutzpflicht’ principle emphasis on the “state’s duty of protection of the public from dangers” tend to conflict with risk governance norms for delineating acceptable/unacceptable risks (Krieger 2012, p. 15). The doctrine calls for equality of treatment in terms of risk related to life and individual freedoms. In contrast, in the US, quantitative risk assessment is entrenched in its systems, with the focus being on prohibition, e.g., gun ownership restrictions, to prevent risks.

Risk Governance Issues in the Public/Government Sector

Risk communication is a key issue in risk governance within the public sector. Well-framed communication is vital for successful risk governance, as it fosters multi-actor trust relationships. Palermo (2014) establishes that defining the best practices is crucial to successful risk governance in innovation-oriented public service organisations. The important skills of an effective risk manager are communication and relationship-building abilities, which relate to the principle of technocratic financial accountability. Risk communication requires a social learning approach and institutionalised transparency systems to promote an open and inclusive assessment of the risk. The main challenge here is how to promote effective multi-actor interaction and inclusion given the diversity of views and backgrounds. Social learning helps identify the effective communication strategy and inclusion level appropriate for a particular context or public actors. Inclusivity also has implications for risk framing and pre-assessment, as public values and concerns often determine the acceptability of risk governance interventions.

A second issue is how to integrate the diverse knowledge/experiences of the actors into the risk governance process. The consideration of the diverse risk perceptions and values in risk assessment is suggested as a way of developing effective solutions to identified risks (Palermo 2014). Therefore, the risk governance in public institutions requires multidimensional evaluations, as scientific assessments cannot be adequate. Effective risk assessment goes beyond probability determination and cause-effect quantification. The integration principle requires the additional consideration of important values/issues like reversibility, equity, etc. (Assmuth 2011). Effective risk governance involves a risk-benefit analysis and trade-offs related to systemic risk or risks.

A third issue relates to the uniqueness of each risk problem. As Rothstein et al. (2013) write, establishing routines/conventions for risk governance is difficult given the “uncertainty, ambiguity, and complexity” of risks (p. 219). As such, public actors and institutions must engage in a reflective discourse to balance the benefits and adverse effects of risk. A prudent precautionary approach is necessary to capitalise on the opportunities inherent in the risk while mitigating its effects. The key question here is what level of uncertainty/effect the stakeholders can endure receiving the benefits of risk.

The risk governance process often culminates in regulations/standards. However, the institutionalisation of rigid guidelines results in reduced flexibility that impedes creativity (Rothstein et al., 2013). Further, the rigidity affects the system’s responsiveness to unexpected risks. Therefore, the regulatory systems in public service organisations do not necessarily eliminate the probability of a risk occurring. On the contrary, the institutions should adopt “knowledgeable oversight” in risk management, as the responsibility of risk governance is not a preserve of the government (Power 2016, p. 15). However, delegating the ‘knowledge oversight’ responsibility to multiple actors introduces the challenge of accountability in public service provision (Andreeva, Ansell & Harrison 2014). Innovative regulatory standards can help promote accountability and risk governance in the public service sector.

Summary

In this paper, a systematic review of scholarly literature on risk governance has been done. Although risk governance definitions vary widely, they all feature multi-actor involvement and transparency/accountability principles. It can be conceptualised as a multi-stakeholder network/process for evaluating and managing public risks. Risk governance provides a framework for the involvement of all actors in responsible management of risk problems. The major risk governance frameworks reviewed in this paper include Brown and Osborne’s (2013) model for public service innovation, IRGC model, modified IRGC framework. Risk governance is a cyclic process comprising five interconnected phases that culminate in an optimal risk management option for an identified risk. The adopted risk governance approaches in public service organisations in countries such as the UK focus on the institutionalisation of risk analysis tools to support policy/decision rationales and accountability. The identified issues of risk governance in the public/government sector include the communication/inclusion of multiple stakeholders, multidisciplinary knowledge/experience integration, routines, and flexibility of regulatory approaches.

Reference List

Andreeva, G, Ansell, J & Harrison, T 2014, ‘Governance and accountability of public risk’, Financial Accountability and Management, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 342-361.

Assmuth, T 2011, ‘Policy and science implications of the framing and qualities of uncertainty in risks: toxic and beneficial fish from the Baltic Sea’, AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 158-169.

Bernado, D 2016, Risk analysis and governance in EU policy making and regulation: an introductory guide, Springer International Publishing, Geneva, Switzerland.

Brown, L & Osborne, S 2013, ‘Risk and innovation’, Public Management Review, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 186-208.

Flemig, S, Osborne, S & Kinder, T 2015, Risk definition and risk governance in social innovation processes: a conceptual framework, LIPSE Project, Edinburg, UK.

Jonsson, A 2011, ‘Framing environmental risks in the Baltic Sea: a news media analysis’, AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 121-132.

Karlsson, M, Gilek, M & Udovyk, O 2011, ‘Governance of complex socio-environmental risks: the case of hazardous chemicals in the Baltic Sea’, AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 144-157.

Klinke, A & Renn, O 2012, ‘Adaptive and integrative governance on risk and uncertainty’, Journal of Risk Research, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 273-292.

Krieger, K 2012, Putting varieties of risk-based governance into institutional context: the case of flood management regimes in Germany and England in the 1990s and 2000s, King’s College, London, UK.

Lodge, M & Wegrich, K 2011, ‘Governance as contested logics of control: Europeanized meat inspection regimes in Denmark and Germany’, Journal of European Public Policy, vo. 18, no. 1, pp. 90–105.

Lofstedt, R 2011, ‘Risk versus hazard–how to regulate in the 21st century’, European Journal of Risk Regulation, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 149–168.

Palermo, T 2014, ‘Accountability and expertise in public sector risk management: a case study’, Financial Accountability and Management, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 322-341.

Power, M 2016, The risk management of everything: rethinking the politics of uncertainty, Demos, London, UK.

Renn, O 2011, Risk governance: coping with uncertainty in a complex world, Earthscan, London, UK.

Renn, O, Klinke, A & van Asselt, M 2011, ‘Coping with complexity, uncertainty and ambiguity in risk governance: a synthesis’, AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 231-246.

Roeser, S, Hillerbrand, R, Sandin, P & Peterson, M 2012, Handbook of risk theory: epistemology, decision theory, ethics, and social implications of risk, Springer, Heidelberg, Germany.

Rossignol, N, Delvenne, P & Turcanu, C 2015, ‘Rethinking vulnerability analysis and governance with emphasis on a participatory approach’, Risk Analysis: An International Journal, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 129-141.

Rothstein, H, Borraz, O & Huber, M 2013, ‘Risk and the limits of governance: exploring varied patterns of risk-based governance across Europe’, Regulation & Governance, vol. 7, pp. 215–235.

Rothstein, H & Downer, J 2012, ‘Renewing DEFRA: exploring the emergence of risk-based policymaking in UK central government’, Public Administration, vo. 90, no. 3, pp. 781–799.

van Asselt, M & Renn, O 2011, ‘Risk governance’, Journal of Risk Research, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 431-449.