Introduction

Mining is a multi-billion dollar industry that provides massive employment to millions of people worldwide. On the flip side, however, mining especially of oil and precious stones is ironically more of a “curse” than a blessing. There is nowhere in the world when mining generates wealth and negativity like Africa, a continent that is blessed with massive mineral resources. This thesis proposal will mainly concentrate the analysis of the competitiveness analysis of gemstone artisanal small scale mining (ASM) value chain on key issues, constraints, and opportunities of small scale precious stone miners in the Erongo Region of Namibia and comparing them to ASM in the Karas Region. The main objective of the study is to find out the key issues affecting mining trends in the small-scale gemstone mining industry with Namibia being the case study.

In this study, the terms artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM) and Small Scale Miners (SSM) will be used interchangeably. Empirical evidence shows that Namibian artisanal mining is characterized by labor-intensiveness, low capital investments, low degree of mechanization, basic equipment, high degree of occupational risks, and is regarded as both informal and formal. Lock & McDivitt assert that according to the International Labour Organization, to some people small-scale mining may be “dirty, dangerous, disruptive and should be discouraged (98). To others, it is profitable, productive, or simply the only way out of poverty”. This is true for many if not all artisanal and small-scale miners in Namibia for whom small-scale mining provides the much-needed income used in many households( National Planning Commission 2008b). To a certain extend, artisanal mining improves the living standards and livelihoods of many people.

Background

To better understand small-scale gemstone mining, it is important to have a look at the background of the industry. According to Hilson (2006), an estimated 13 million people worldwide were involved in small-scale mining activities, and that another 80-100 million people were depending on it for their survival (23). In Namibia employment due to small-scale mining in both legal and illegal mines was estimated at a total of 102 000 people in the year 2011. In almost a hundred years of the existence of artisanal mining activities in Namibia, this sub-sector has continued to employ workers to unearth semi-precious and precious stones. It is important to note that Namibia is a middle-income country with an unemployment rate estimated at 52%. Unemployment is much higher in the rural areas among the youth. Over 60% of Namibians reside in rural areas. Namibian National Development Plans (NDP 1-NDP 4) emphasize the importance of small-scale mining as an important strategy of poverty alleviation.

Erongo region and Karas Regions are two of the thirteen political regions of Namibia. In 2010, Erongo Region and Karas Region registered a population of 378 000 people which constitutes 7 percent of the total Namibian population. The total population is made up of 68 percent males and 32 percent females. The average household size is 3.6. The Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) invests heavily in the Erongo region to assist the activities of small-scale miners. Also, the European Union Delegation to Namibia sponsored $1.3 million to support ASM in the Erongo Region through the Association of Small Scale Miners (ARSM) with capacity building in the form of business management and logistics. So far, several small-scale miners in the Erongo Region are formalized. In the Karas Region, all the ASM interventions are at an infant stage. The mining activities in this sub-sector involve the extraction of gemstones, crystal specimen, tantalite, and cassiterite. The gemstones extracted include fluorite, dioptase, topaz, aquamarine, quartz, amethyst, tourmaline, and garnet. Some of the small-scale miners in the Erongo Region have valid Non-Exclusive Prospecting licenses while others operate illegally (Macintyre & Lahiri 49).

Research Problem

Like any other African Country, Namibia is finding ways to alleviate poverty to accelerate economic development and increase competitiveness using natural resources especially mining. However, abundant natural resources in themselves are not sufficient for poverty alleviation, economic growth, and prosperity, but rather in the value –addition of products and services associated with them. Gemstone mining in the Erongo Region is one of the projects where various stakeholders have invested with the primary aim of alleviating poverty and economic development. However, there are a lot of issues that dictate the mining industry dynamics especially those of small-scale miners. Therefore, the effectiveness of the above initiatives is not clear, hence the undertaking of this study.

Rationale and Purpose of the Study

The Purpose of studying small-scale mining in Erongo (Namibia) is that it would provide the latest information on value chain competitiveness analysis of semi-precious small-scale mining to create sustainable employment opportunities, enhance economic growth and therefore reduce poverty. The information will also be useful to policymakers in their quest to formulate policies, strategies, and activities that will effectively alleviate poverty. The previous intervention strategies by stakeholders like the European Union, Government of Namibia, investors, and donors; although in the right direction, did not achieve much. The research will also help focus on the dichotomy of small-scale mining, employment creation, and poverty alleviation. Also, the study will help focus on the finer details concerning social, occupational, and environmental concerns. On the other hand, the recommendations from this analysis will contribute to current public policy efforts to create enabling environment for small scale mining

Research Objectives

- The study will be aiming to fulfill the following objectives.

- To find out whether gemstone small scale mining value chain is competitive

- To identify how much upgrading has taken place in the gemstone mining value chain.

- To identify the major constraints to ASM value chain competitiveness.

- To identify further opportunities for upgrading in the value chain.

- To develop a competitive strategic action plan for eliminating constraints and enhancing sustainable improved performance.

Key Research Questions

The research will be seeking to answer the following questions:

- How much upgrading has taken place in the Erongo Region gemstone mining value chain?

- What are the major value chain constraints and issues to competitiveness?

- What and where are the opportunities for upgrading in the value chain?

- How competitive is the gemstone value chain and what can be done to make it competitive?

Statement of Hypotheses

Throughout the research, the study will be focusing on the following hypotheses:

- Research Hypotheses (H1): Constraints prevent competitiveness in gemstone small-scale miners.

- Null Hypotheses (Ho): Constraints do not prevent competitiveness in gemstone small-scale miners.

Literature review

A lot of research has been carried out on mining activities in Africa especially in Namibia. Specifically, there is a big body of research on mining activities of small scales miners in Africa, especially in the southern region stretching from Zambia to South Africa. According to, mining is one of the most important economic sectors of Namibia. The sector accounts for slightly over 25% of the country’s total revenues. It also accounts for over 10% of Namibia’s gross domestic product. According to Campbell (a), a large section of the mining industry in Namibia is undertaken by small-scale miners, some of whom operate through cooperative societies while others operate individually (88).

Research methodology

The research will utilize the random stratified sampling methodology to collect information from participants. Data analysis will be done through the use of SPSS software. All the regions to be covered in the study will be arranged into different strata from which participants will be randomly chosen to participate in the study.

Research Limitation

The research is mainly focused on the identification of the Key Issues, Constraints, and Opportunities of Small Scale Semi-precious Stones (Gemstones) in Namibia. As mentioned in the methodology section, the research will take place through the study of a sample that will be randomly chosen. While the accuracy of the study may not be questionable, the generalization of the results obtained on the ASM population of Namibia may be somewhat misleading. Somehow, the results of the study may fail to give a clear picture of the situation concerning the study subject.

Research Ethics

The research will follow all the required rules and ethics of research. All participants taking place in the study will be doing so voluntarily. Before the study, research assistants will explain to the participants in detail what the study is all about. They will also explain to the participants that the research will be for academic purposes only and not for any other purpose. Participants will be required to sign an agreement form consenting to the knowledge of what the research entails and their voluntary participation.

All participants will be free to choose whether to use their real names or pseudo names for purposes of privacy and confidentiality. All participants will be free to withdraw from the study at any time without any penalty.

Literature review

The Artisanal and Small Scale Gemstone Value Chain

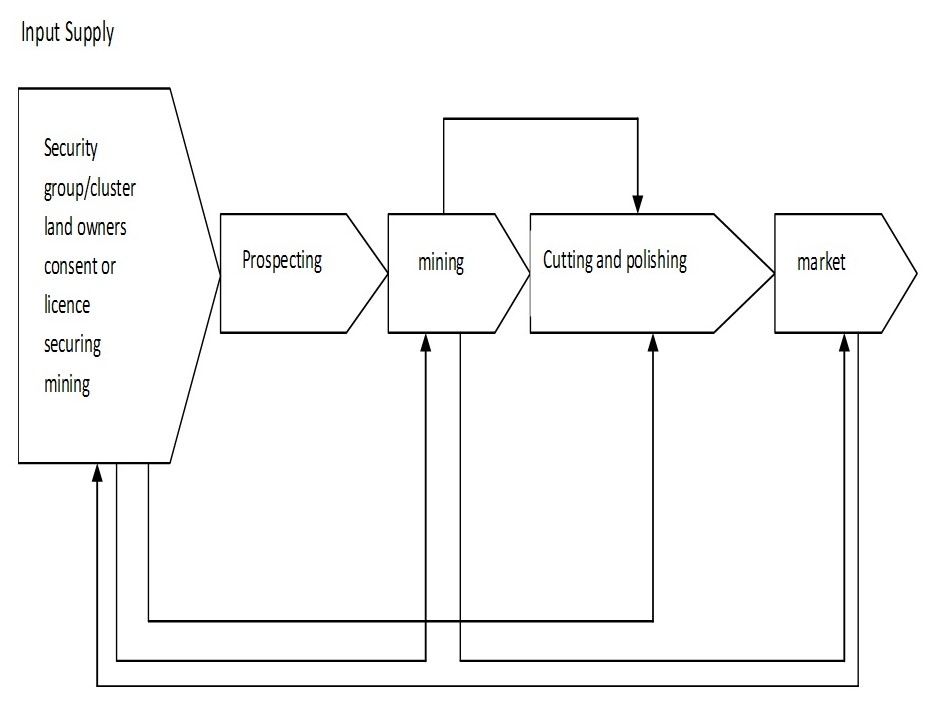

Botchway defines the gemstone value chains on small-scale mining as a full range of processes, activities, actors, and locations that are required to bring a mining gemstone product from its prospection to the world market (105). In general, the value chain involves exploration, mining, sorting, polishing, manufacturing, and marketing as illustrated below.

This literature review will be aiming to highlight the body of knowledge that exists and that relates to the dynamics of small-scale mining in general and in Namibia in particular. In this chapter, there will be a special emphasis on the value chain process, a critical component of the small-scale gemstone mining process. There will also be a detailed look at the key issues, constraints, and opportunities in gemstone artisanal small-scale mining. When small-scale gemstone mining is put into perspective, various issues come into play. They include poverty, the role of women, labor especially child labor, and social impacts of the trade. The review will also deal with the constraints, opportunities, and availability of resources and capital to engage in the business.

The Value Chain Program

- Mining: Open-pit mining and underground mining are the two main ways used by semi-precious stone miners. The small-scale miners use basic tools, equipment, and machinery. Using the mining techniques that suit a particular situation is crucial to ensuring the most suitable conditions.

- Sorting: Rugged stones of semi-precious nature are grouped into different categories depending on variables such as size, color, and quality. The best semi-precious stones are sent off to the next stage of the value chain of stone polishing, jewelry manufacturing, sold, and exported as souvenirs.

- Cutting and Polishing: Cutting and polishing normally occur in different locations. They are shipped out of the country to undergo further processing in the countries where major dealers originate from, here the value is tremendously added and is reflected through the assigned mark-up range. More often this particular stage is referred to as the ‘globalization’ stage of the process. The nations that develop the most cost-effective methods of gemstone processing and polishing technically take the leadership in the quest to dominate the gemstone global market. The value chain is sustained by activities carried out by the actors who vary from large-scale industrial actors to small-scale miners like the miners in Erongo Namibia (Campbell 18).

Actors in the Value Chain

Table 1: Actors in the ASM Value Chains

Key Issues, Constraints, and Opportunities in Gemstone Artisanal Small Scale Mining As mentioned earlier, this section will focus on the key dynamics that are the main subject of the paper. Though they are summarised in the table below, the following subsections exhaustively examine them.

Typical Issues, Constraints and Opportunities of ASM

Table 2: Typical Issues, Constraints and Opportunities of ASM

Issues

In its report, 1999, the International Labor Organization reported that in a questionnaire which was distributed to different government employers’ organizations and mining unions in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, 15 possible issues affecting small-scale miners were listed whereby respondents chose ‘obtaining finance’ as the number one issue affecting them. Environment, safety, and technical assistance were also at the top of the list of issues that were considered to affect small scale miners the most, and other issues such as; obtaining equipment, need for training, obtaining permits and occupational health also received a considerable amount of votes (Oden 23).

Other issues that were cited were transport, tax regime, job security, child labor, working conditions, and selling arrangements altogether accounted for only 20 percent of the votes. In Namibia, artisanal miners are unable to secure loans from banks and other financial institutions for their starting capital and this is especially the case for female miners and for miners who operate without licenses (Priester et al. 88). This might be due to lack of collateral and the possible inability and unwillingness of the miners to pay back their loans.

One of the most comprehensive research studies on the subject is the one by Nyambe and Amunkete (2009). They studied Small –Scale mining in the Erongo Region of Namibia and its impact on poverty alleviation in Namibia. Botchway summarises similar studies as Dreschler (2001) studied Small-scale Mining and Sustainable Development within the SADC Region, Krappmann (2006) studied tantalizing, tungsten, and gold mineralization suitable for small-scale mining in Namibia and qualitative survey of metal occurrences and assessment project (34).

Also, Ellmies, Hahn, and Mufenda (2005) are cited who gave an excursion ‘Report to Small-scale Mining in Namibia’, Appel (2010) who studied environmental impacts of small-scale mining, Galfi (2000) who studied Neuschwaben diggers, ‘NAMDEB’ and Tourmaline, Senauer (2002) who studied a pro-poor growth strategy to 2002. All the above-mentioned studies explore possible contributions of small-scale mining to poverty alleviation in the region and Namibia the above-mentioned studies have a keen interest in the study of the poverty trends in Namibia and their relationship with small-scale gemstone mining. Nyambe and Amunkete’s study aimed at exploring the poverty in the region, its relationship with the economic activity and to provide a basis for decision-making for authorities and other stakeholders.

ASM and poverty

The link between ASM and poverty is profound and complex. Speiser says that ASM plays a very important part in poverty reduction in Africa. Fifty percent of the workforce in Africa is involved in mining and 40% of that workforce is engaged in artisanal small-scale mining (46).

Those who constitute the majority of the ASM community at the level of resource extraction, basic processing, and local trading, provide that the resources are inefficient and the environment is not sustainable. Levy argued and concluded that ASM can perpetuate poverty. In Namibia, one could argue that those in ASM generally live in poverty. Books argued that they are often driven into ASM by poverty and the income they receive from ASM can improve their daily subsistence and reduce their impoverished status in the immediate term (53). However, the nature of the activity is exploitative. It draws people away from other more sustainable activities such as agriculture. It does not produce long-term wealth for these individuals, rather, creates debt. ASM helps them move from extreme poverty to poverty.

ASM is driven by poverty

Speiser asserts that many ASM workers are engaged in the trade because they have no jobs and no alternative options (23). In places where the previous, formal economy has collapsed due to war, political instability, and corruption, ASM can arise as a survival strategy for those who live on and around mineral-rich land. It can be used as a general guideline that miners typically receive around a relatively small percentage of the local sale value of their product.

In Erongo Region, towns like Karibib and USAKOS are supported by the proceeds of ASM. A larger proportion of this money enters local circulation through a variety of actors, the largest proportion being through the trader, where it pays for services directly associated with the mining activity such as the provision of tools, equipment, fuel, food, housing, and health. It also creates other types of jobs, purchases of goods which include essential basics and luxury items from local suppliers, create a demand for transport services, pays unpaid state agents, and stimulates economic activity. Firestone concludes that despite exploitation of the workers in the mines, ASM generates a high level of social access to the economic value of their product by generating a significant cash flow through the community (41).

Constraints and Issues

Access to Finance

Access to finance is essential to enable the formalization, improved production, strengthening of artisanal mining, and its potential transformation into small-scale mining or medium-scale mining (Oden 67). However, such finance is difficult to come by at all stages in the value chain. Hilson says that artisanal miners typically present a suite of factors that make them unattractive to lenders. First, they tend to be already in debt. Second, they are frequently migratory, and ensuring potential repayment of credit is difficult. Third, they usually lack collateral. Fourth; they rarely have the capacity or expertise to be able to present a viable business plan for why they need the credit or how it will be effectively used. Fifth, Books also said ASM is rarely well-reported statistically and therefore does not allow for risk analysis by creditors (92). And finally, there is a dearth of lending institutions that provide this type of credit or support for ASM. Given these constraints, Artisanal miners usually resort to the most accessible local source of funds, namely pre-financing by traders, which further compounds the problems of debt as these loans may demand high rates of interest and sale of the product to the trader at a sub-optimal price for the miner (Gereffi 91). There is a need for innovative financing arrangements to address this conundrum.

According to Hilson, ASM communities frequently have a significant amount of potential capital moving through the system; however, this is widely dispersed and tends to be spent on short-term needs, either for survival or for luxury items that relieve the tedium of the work (32). Alternatives to direct finance can also be used. For example, in Namibia, a project of hiring equipment from Erongo Regional Council has been successful in upgrading the miners to a certain extent of equipment and tools provided.

Mining Equipment, Tools, and Machinery

Access to finance or lack thereof has a ripple effect on the small-scale mining of gemstones. One of the reasons why small-scale miners are classified as small-scale miners is because of the kind of equipment and machinery they use. Campbell (b) indicates that in many African countries, small-scale miners use traditional techniques and low-level equipment in excavation or digging (33). In Namibia, miners use rudimentary tools, manual devices, or simple portable machines. According to Nyambe and Amunkete, these tools are not sufficient to carry out mining activities. This makes the miners not perform to their maximum capabilities. This lack of equipment is worsened by the fact that miners do not have starting capital to acquire the tools they require. More so, miners have no access to credit from formal financial institutions for them to finance their operational requirements. Botchway quoting an excursion report titled ‘Excursion to Small-scale Mining Operations in Namibia’, lists the challenges faced by small-scale miners at Farm Neuschwaben, a small-scale mining community in the Erongo Regions (71). Lack of adequate mining equipment is the biggest challenge and difficult unsafe excavation conditions, the need for capital during periods with no tourmaline, absence of a buyer’s scheme organized by the government, and sanitation are the next on the list.

Gender Issues in Small-Scale Mining

One of the hallmarks of the economic landscapes of developing countries like Namibia is the skewed nature of the gender gap in the labor market (Speiser 103). It is estimated that women constitute 40-50% of the ASM workforce in Africa. Empirical evidence indicates the same for Namibia. Women frequently use ASM as a supplementary income source, often seasonally, and their presence around the mines may be less visible, so they may be excluded from estimates. The International Labour Organization (1999) in its report for discussion at the tripartite meeting on Social and Labour Issues in Small Scale Mining of 1999 indicated that about four million women are involved in ASM worldwide. Namibia is recorded to have a proportion of up to 10% or more. This number is low because the mining process is very taxing and the risks are high in that one is not sure of the outcome even after extensive prospecting. Speiser says that quite a several women are involved in hand napping of stone aggregate (55). These women operate illegally and the government is working on a system where these women will be able to form or be part of associations so that their activities can be facilitated and government can tax them. Levy further explains that within this sector, women are involved in the more informal work of Small Scale Miners such as panning (38). However, despite the increased representation of women in small-scale mining and apart from the challenges faced by all small-scale miners, women still face some challenges unique to them as women.

Lock & McDivitt also agree that women in ASM face challenges like; security, health, and social risks. Firstly, health risks occur due to lack of sanitation in camps, malnutrition, and physical trauma from the difficulty of manual labor. Secondly, women in mining camps can suffer miscarriages due to injury and stress. Thirdly, Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) and abuse are prevalent in the mines. This is a serious risk for women working in ASM. SGBV can take many forms. A recent study carried out in the DRC, which has the worst rate of rape and sexual abuse in the world, identified that ASM situations pose significant risks of SGBV for women and children, family break-up, and polygamy.

Child labor in ASM

Another sensitive issue besides gender imbalance in gemstone mining is child labor. It is understood to be caused by poverty, but, at the same time, there is no clear thesis on how it contributes to poverty. In some areas, children may constitute a significant component of the ASM workforce. This is universally condemned by the UN Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labour yet, in many countries, even if there is national legislation that bans children to work in mines, enforcement may be severely lacking. ASM can have serious repercussions on children’s physical and mental health and moral wellbeing, as well as disrupting or preventing their access to education. Conversely, ASM may be the only livelihood. In 1999, the ILO estimated that there were 13 million ASM workers worldwide, one million of whom were children. The UN Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labour (No.182, 1999) identifies mining as “work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out is likely to harm the health, safety, and morals of children”. Cairncross says that children face many risks in mines including physical trauma, injuries, hernias, backache, eye damage, damage to growing bones and organs, asphyxiation, mercury poisoning, lung and skin disorders, water-borne disease, malnutrition exposure, and addiction to alcohol and drugs (39). Nyambe and Amunkete add that prostitution, trafficking, STDs, HIV-AIDS are risks children are exposed to in mines (100). ILO, through the member countries, has taken a two-pronged approach to eradicate child labor. Firstly, upstream action is aimed to create a policy-making environment conducive to the regularization of ASM operations. And secondly, downstream activities should monitor children in the mining areas, and withdraw those from work and place them in school or training facilities.

Social impacts of Artisanal Small Scale Mining

Firestone quoting the National Planning Commission reports that as the camps are established, service providers (often women) move to the camps to gain employment in minerals transporting, washing, sorting, grading, or treatment (32). They also come to trade essential goods, provide tools and materials, set up restaurants, or gain employment in the sex trade. Mining camps can be highly vibrant economic entities, albeit sometimes short-lived (Macintyre & Lahiri 25). They can often cause rampant local inflation.

National Planning Commission (1999) reported that camps become established on an ad hoc basis, particularly in response to a minerals ‘rush’, or if they over-run an existing village or community; sanitation and hygiene conditions are often extremely poor creating health hazards. This is compounded by the often promiscuous lifestyle associated with some ASM where the daily cash payment for minerals is sometimes used for alcohol, drugs, and payments to sex workers. All of these can compound the risk of the spread of STDs, including HIV/AIDS (National Planning Commission (2006/ 2004, 2006). The migratory nature of ASM can also give rise to polygamy if miners abandon families or start new families in mining areas.

Health and Safety

Oden asserts that the health of a nation has a significant impact on the economic direction of that particular country (22). ASM works in dangerous conditions. According to Levy, several deaths have been recorded in many SADC countries as a result of small-scale mining; however, more deaths have been recorded in large-scale mining in total. During the eleven years between the years of 1984 and 1995, a total of three hundred and twelve large-scale miners had been killed in comparison to nine small-scale miners in Zambia (Books 89). The absence of machinery means that work has to be done manually, thus resulting in fatalities. According to Firestone, many mines are not carefully planned because they are illegal and therefore, structures are made in such a way that they are easily concealed (63). In many countries across the world, including Namibia, measures for the prevention of mining accidents and other fatalities either do not exist or are not properly enforced. In Erongo, more than 5 miners died in mining shafts in the past 3 years.

Health problems of dust which causes silicosis, noise which causes tinnitus, and chemical pollution which includes cyanide and mercury are evident in ASM. These chemicals cause diseases such as tremors, difficulty in walking, tunnel vision, psychological problems, cancer, or even death. In addition to these health problems, there are a lot of cases of physical injury within the mines due to rockfalls and mine collapses. Campbell (a) adds to the list,

accidents with machinery exposure, physical stress due to the exertion and difficulty of the work, fumes, and gases causing respiratory problems, exposure to noise which damages hearing, working in poor light conditions which can damage sight. On top of that, there can be psychological stress as well as exposure to substance abuse which can cause mental and organ damage. Besides that, Priester et al add that there are concerns for the health of communities around the mines which include: exposure to chemical and organic toxins in water supplies, inhalation of dust and fumes risks of explosions, floods, landslides, or other crises associated with the destabilized terrain, increased levels of communicable diseases due to poor hygiene and lack of sanitation (106).

The health issue is compounded by a high HIV/Aids prevalence rate. HIV is especially high among adult women. In Africa, HIV/AIDS is significant in the development of communities and poverty reduction. When heads of families who are the primary wage earners fall ill and cannot work, need substantial medical care, or die leaving vulnerable family members behind, the impact is devastating at emotional, social, and economic levels. National Planning Commission (2008) reported that in Namibia, entire sections of the active workforce are HIV positive with significant repercussions for local and national productivity and economic development. Coupled with a skewed gender balance, the health of Erongo becomes a major issue.

Other issues

The issue highlighted above is the major one that defines the trends and dynamics of the small-scale mining of gemstones in Namibia. However, other minor issues play a significant role in the whole process. For instance, Botchway reports that there are significant frequent conflicts between stakeholders in the gemstone mining industry in Namibia.

He says the root cause of conflicts between the small scale miners, artisanal miners, medium to large scale miners, large scale miners and the government is mistrust amongst these parties. ASM workers are seen as illegal by other miners and large-scale miners are seen as exploiters who do not want to share the wealth of the country with local communities. The government is seen to be working in bad faith by all parties and failing to control the situation. As the government is mainly concerned with sustainable issues like the environment, it often clashes with all parties. However, the Rossing Foundation (2012) on their website said that big miners like Rio Tinto are supporting small-scale miners and Small-scale mining in Namibia operates alongside well-established large-scale mines.

Works Cited

Books, Haephastus. Mining in Namibia, Including: R Ssing Uranium Mine, Skorpion Zinc, London: sage Publishers, 2011. Print.

Botchway, Francis. Natural Resource Investment and Africa’s Development, London: Sage Publiocations, 2011. Print.

Cairncross, Bruce. Field guide to rocks & minerals of Southern Africa, New York: Cengage Learning, 2004. Print.

Campbell, Bonnie (a). Mining in Africa: Regulation and Development, London: Sage Publications, 2009. Print.

Campbell, Bonnie (b). Regulating mining in Africa: for whose benefit?, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. Print.

Firestone, Matthew. Botswana & Namibia, New York: Lippincott, 2010. Print.

Gereffi. The Organisation of Buyer- Driven Global Commodity Chains: How U.S Retailers Shape Overseas Production Networks, London: Praeger, 1994. Print.

Hilson, Gavin. Small-scale mining, rural subsistence and poverty in West Africa, New York: Springer, 2006. Print.

Levy, Arthur. Diamonds and Conflict: Problems and Solutions, London: John Willey & Sons, 2003. Print.

Lock, Dennis, and James McDivitt. Small-scale mining: a guide to appropriate equipment, New York: Cengage learning:New York, 1990. Print.

Macintyre, Martha, and Lahhiri, Kuntala. Women miners in developing countries: pit women and others, New York: Taylor & Francis, 2006. Print.

Nyambe, and Amunkete. Small Scale Mining and its impact on poverty in Namibia. A case study of Miners in the Erongo Region, Windhoek: NEPRU, 2009. Print.

Oden, Bertil. Namibia and external resources: the case of Swedish development, New York: Routledge, 1994. Print.

Priester, Michael et al. Artisanal and small-scale mining: challenges and opportunities, Los Angeles: Springer, 2003. Print.

Speiser, Alexandra. Small-scale mining: the situation in Namibia, New Delhi: Thomson Learning, 2000. Print.