Abstract

The purpose for this research is to evaluate the financial sector market of the UK and use the same to give light on how developing countries can build strong syndicated loan market in the future based on lessons learned. The study uses comparative approach, descriptive design, and analytical method to analyse the United Kingdom financial market sector experiences and show clearly the lessons that can be learned from such a country and whether these experiences can be applied in the developing nations. In general, the UK experiences on corporate governance have revealed that superior corporate governance may reduce risks, encourage performance and develop capital market access. This is because marketability of services and goods develops leadership and also raises the value of banks, thereby enabling them to fund firms’ project through advances such as syndicated loans of low rates.

Thus, in an emerging nation corporate governance expands beyond finding solutions to issues emanating from control and ownership separation. The study contributes to the current literature of syndicated loan market by showing ways in which the developing countries can follow to build strong financial systems such as creating strong corporate governance which will enable the banks to be independent and run efficiently without the interference from the government.

Introduction

Generally speaking, financial markets play the role of channelling resources in all nations from the depositor to investor. The significance of this role of the financial sector has obtained much consideration in the latest literature on the growth of the economy. In the very last decade, a strong agreement has materialized that efficient economic intermediaries have an important effect on the growth of the economy (Dennis and Mullineaux, 2000). Current financial systems have an extensive assortment of institutions that are market-oriented for making this process possible. In planned financial systems, this procedure was carried out through governmental initiatives and there were small number of market-oriented fundamentals of the financial market (Mian, 2006).

Therefore, the first stage in the process of change for the economic sector is the advancement of financial institutions that are market oriented. Given the challenges faced by economic sectors in many countries, many spectators anticipate that the changeover process would spread over several years. Actually, several developing countries have made notable progression in the most recent decade of change (Beck and Demirg-Kunt, 2009). Though, banks are generally visible and frequently dominate the financial market, they are merely a component of the financial intermediation process and serve to facilitate the funding activities that distribute resources in the financial system (Bae and Goyal, 2009).

Funding is a process that begins with the businessman and extends to big corporations that are interested in raising the equity in various ways such as through issuance of shares to private placements and global syndicated loans (Boot and Thakor, 1993).

Consequently, there are several methods of funding and various types of financial institutions that facilitate these. The method may be categorized into three wide classifications that include bank lending, entrepreneurial finance and capital market funding (Boot and Thakor, 1993).

Syndicated loan overview

A bank can use several tools to offer loan to its clients for instance syndicated loan, overdraft and bank loans among others. The term syndicated loan explains a tool in which several lenders provide funds to a single borrower, in reality loan syndication is a group of banks (the syndicate) that lends directly to the borrower under a single loan agreement (Dennis, 2000). The lenders usually perceive the syndication as a collection of loan contracts expediently condensed into a single agreement; syndicated loans have become a significant corporate financing technique for large and small firms in developing countries (Armstrong, 2003).

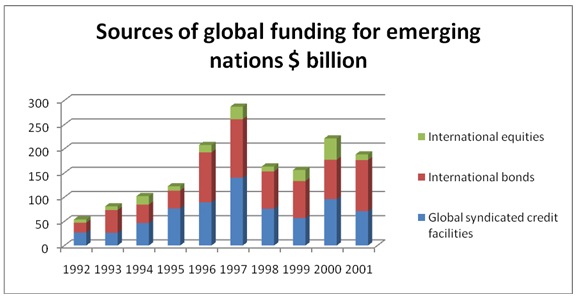

Generally, syndicated loans come from banks with institutional investors, as well as hedge funds, mutual funds, pension plans and insurance firms that are increasingly being concerned with syndicated lending (Champagne and Kryzanowski, 2007). The syndicated loan market has been developing robustly ever since 1990s and amounted to approximately $1,000 billion by the year 1999; in 2004 it further increased to $2,260 billion (Bonin and Paul, 1999). However, from 1993 to 1997 the level of syndicated loans improved gradually but reduced in 1998 following the Russian and Asian financial crises, afterwards it increased considerably in the next two years and decreased again in 2002 and 2003; the highest volume of syndicated loan was attained in 2004 (Bonin and Paul, 1999).

However, the recent financial crisis has affected the international finance and banking foundations and placed the global banking system in an extreme stress. As a result, most of the financial markets turned out to be dysfunctional and a significant number of the global banks were declared bankrupt. This credit crunch originated from developed countries and rapidly shifted to the developing countries (Emerging Market Economies (EMEs), specifically in the repercussion of the Lehman Brothers fall (Avdjiev, Gyntelberg and Upper, 2009). At the height of this financial crisis, cross-border bank loan provision confirmed to be the only means of financially channeling stresses in the global financial system to the individual emerging nations.

In fact, cross-border lending to developing nations decreased sharply during the financial crisis and banks and economies depending on the wholesale financing were hit harder than ever (Avdjiev et al, 2009). This decrease was particularly questioned by policymakers; possibly the most significant one concerned the decline motivators. However, the decrease in cross-border loan provision was related to the global banks that offer such loans like the syndicated credits and a thorough investigation indicates a shady picture of the banks’ function (Baba, Gadanecz and Packer, 2009). Specifically, although global lending dropped considerably during the credit crunch, a minor rise existed in local currency credits offered by global banks to the domestic members. The dissimilarity of global banks highlights this outcome much better; for instance, Mexico proposed that centralized global banks were more expected to react to the domestic market interruptions and restrict lending than the global banks that are decentralized (Baba et al, 2009). It is based on this background that this paper intends to develop a working framework that can be used by developing countries to strengthen their syndicated loans, and by also reviewing documented lessons from developed countries, in this case UK.

Problem Analysis

Currently, the market for syndicated loan is more intricate than before because of counterparties crossing geographic and political barriers as trade agreement continue to develop in the international financial system and as the global network of syndicated loan criss-crosses the world (Hermes and Robert, 2000). Syndicated lending entails parties from all these regions, namely Europe, Asia, U.S., Latin America, Africa and Middle East (Hermes and Robert, 2000). The developing countries vary in size from large nations such as China to moderately small nation like Hungary including others such as Slovenia and Estonia (Blejer and Marko, 2001).

The degree to which dissimilar factors of the financial market institutions grow will be determined by the country size; at the end of the day, small nations are not likely to nurture and develop the full range of institutions and markets. In such circumstances access to international financial and foreign capital markets will exchange with the domestic institutional growth. The trend is not limited to developing markets although it is an attribute of small nations that are well-developed (Bonin et al, 1998). The emerging countries syndicated loan markets such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) must be measured up against frontier countries syndicated loan market as opposed to the developed countries such as United Kingdom (Bonin and Paul, 1999).

Nonetheless, the real sector irregular growth and financial market immaturity leave the developing countries with wide open institutional and legislative gaps in their economic spectra. Additionally, development approaches have been rejected because of taking long time considering the significance of the economic sector to the contemporary economy (Blommestein, 1998).

Therefore, any investigation of the developing countries must take into consideration the growth of the financial institutions as well as the significance of the “missing pieces to the overall functioning of the financial sector” (Blommestein, 1998).

In general, developing nations usually have institutions which are not well developed and particularly have lesser credibility on their central banks, than developed nations. The lower credibility frequently stems from price instability history as well as hyperinflation in a number of cases which is attributable to historical dependence on government funding in presence of undeveloped fiscal system (Bonin et al, 1998). In addition, the uncompetitive system of the financial institutions plays part in contributing to the problem of public finance that is conventional dependence on banks as the only source of funds, including use of financial repression combined with capital controls (Bonin et al, 1998).

Additionally, developing nations are viewed as high-risk countries because of high default risk on loan borrowed; thus, international lenders will charge high rate of interest especially given that their financial markets are faced with high imperfections such as loans from bank made under management direction, poor property right protection and government corruption. In this case therefore, the emerging nations as well as frontier markets require different models than those applied in the developed nations. It is thus the intention of this paper to contribute towards such a formation of strong syndicated loan market in these developed countries considering the inherent weaknesses in their financial institutions and business environment in general.

Problem statement

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to process evidence as well as analyse information that will enable us to arrive at an informed conclusion of whether the present financial system in the developing countries need to be improved especially the banking sector, which is critical in facilitating the provision of loans to firms in need of funds. It is also the purpose of this study to analyse how the syndicated loan market has evolved by evaluating factors that motivated it in UK to its current advanced level.

Justification of the study

A considerable number of developing nations have taken significant financial restructuring in the last few decades; these reforms consisted of privatization of the banks as well as the bank’s product such as the loans used to finance firms. These loans include both long-term and short-term for instance syndicated loan. However, syndicated loan experience for most emerging nations in present years appear to propose that reforming the structure of the system of finance is a complicated process that presume a deep comprehension of the whole set of relations between the banks. Simultaneously, the present experience of the UK financial market may be used by the developing nations in designing their financial system to allow for the development of the syndicated loan. The syndication process must be regulated correctly through strong institutional capacity that is also very expensive, but still very important process.

One of the challenges is the bank-based system of finance for emerging nations since they face challenging issue on how they should set up their system of finance, what type of system they should implement and what type of system of finance would most effectively promote growth and economic development.

Therefore, this study intends to investigate whether the UK financial market experiences can be used by the developing nations in reforming their financial system in similar manner. This study will contribute to the not so much literature sources that exist which investigates the developed nation’s experiences and lessons that can be learned, but with a special focus in UK financial market.

Study objectives

- To investigate the suitability of syndicated loan models being applied in the developed countries and suggest ways to improve on the same that factors in the challenges experienced by emerging countries.

- To find out the reasons behind the differences between emerging and developed financial system

- To investigate existing challenges in the financial sector of developing countries and recommend financial strategies that can be applied to bridge the gap that exist between emerging nations and developed countries by using UK as a reference point.

Organization of the study

The lessons from United Kingdom financial market sector, mainly in the perspective of the developing countries will provide the focal point of this study. This study will focus on one element of the financing continuum that has obtained more consideration in the developing countries; this is the banking sector, which offer syndicated loan (Le, Gasbarro and Zumwalt, 2007). In the next section of this paper, this study will discuss about syndicated loan market evolution in general by giving broad summary of the problem, then demonstrating its theory based on each country experiences and will eventually finish by discussing the implication of these occurrences to the developing countries.

Since banking is a critical concept for this study, it will be exhaustively discussed in the literature review section because of the role it plays in the syndicated loan process in offering loans. In the same section the knowledge gap will be identified in the syndicated loan market which the researcher will fill to add to the existing literature. This study will not be the first to report on the United Kingdom financial market sector but is unique in that it seeks to investigate and review documented lessons that can be used to strengthen syndicated loan market in emerging nations.

In generally, the literature centres on particular problem of change such as restructuring but less attention has been paid on the financial market sector. This is because attention on the financial market sector is frequently an element of a wider concentration in macroeconomic strength and the function of the monetary policy in controlling inflation. Though the output level in a number of developing countries is below the peak level, significant improvement has been done (Barnish, Miller and Rushmore, 1997). The issues of undeveloped countries are similar to those affecting other nations around the globe; for instance, the financial deficit and capital sufficiency of banks are issues affecting many developing countries. Thus, the limitations of Central Asia states for instance are the same as those being experienced in the least developed countries in Asia and Africa (Barnish et al, 1997).

Literature review: Banking Sector and Syndicated Lending

Business Finance

Business or corporate finance is regarded as the mean of raising finances for advancement of a business that already exists; in such a case a firm can use debt or equity to fund the business operations. Debt finance is given preference over equity finance when it comes to profit distribution although debt funding in contrast only earns a fixed return on debtholders (Davis, 1996). In some situations, the finances needed may be so huge forcing more than one financial institution to come together to carry out the funding through loan syndication process, which has the disadvantage of being time consuming. The provider of corporate term-loans has a remedy to the assets of the corporate raising funds and retained earnings consist of a huge proportion of the sources of funds (Davis, 1996).

Project Funding

Project funding is when finances are raised to carry out a particular project. Multinational corporations have an extensive range of funding alternatives available to fund any practical selected projects that is selected through existing criteria. These restrictions came about when selecting project funding that require financing and include public sector funding restrictions, firm’s consolidated statement of financial position restrictions and the contractual regulation as well as focus enforced on the project managers operating on contracts in the execution process with borrowed finances (Davis, 1996).

Project funding discipline takes account of understanding the underlying principle for the project being funding, how to set up a financial plan, evaluate risks, design funding mix and also raise finances.

Additionally, a firm should comprehend the cogent evaluation of why a number of project funding plans have thrived whilst others have not succeeded (Davis, 1996). An information-base is needed before considering the blueprint of any contractual planning to sustain project funding such as governmental provisions, private or public infrastructure joint ventures, private or public funding systems; loan needs of creditors as well as how to establish the borrowing capability of the project (Tinsley, 1996). Other information needed pertains how to set up cash flow predictions and utilize them to gauge anticipated rates of required return, accounting and tax considerations in addition to analytical techniques needed to authenticate the feasibility of the project (Tinsley, 1996).

Emerging nations

The terms “developing” and “Emerging” nations are used interchangeably to mean any country with middle-to-low income per head; developing nations comprise of about 80% of world populace, representing approximately 20% of large-scale economies (Luo, 2002). Emerging nations have been in existence for many years, and most of the time they have tried two mixed and linked strategies in dealing with challenges of syndicated loans that include; drawing on global investment and developing their financial markets or institutions (Luo, 2002). A development in overseas investment of an economy for instance is a sign that the economy has been successful in building confidence in its economy.

The term used in describing these countries markets have considerably changed over time; in 1950s and 60s, these countries were described as “underdevelopment nations” but in 70s and 80s the term was refined to “less developed nations” and from 1990 up to date they are termed as “Emerging Financial Markets” (EMEs) (Luo, 2002).

This change of name reflects the change of world’s ideas, moving towards free market from the state-sponsored growth which has brought about bust of development and performance. Luo (2002) has defined emerging nation as

“a country in which its national economy grows rapidly, its industry is structurally changing, its market is promising but volatile, its regulatory framework favors economic liberalization and the adoption of a free-market system and its government is reducing bureaucratic and administrative control over business activities” (Luo, 2002).

Although, Luo (2002) recognized it is actually deceiving to presume that all developing nations are same since he discovered a number of differences and commonalities that run across them. The general factors recognized include first, legal infrastructures in these economies mainly consist of legal structure advancement and implementation, which are commonly weak (Luo, 2002). Secondly, institutional support and market factors for the country growth and business advancement are normally weak (Luo, 2002). The factors market like labor market, capital market, forex market, information market and raw materials markets are normally less developed and yet usually intervened by the governmental departments and institutions (Luo, 2002).

Third, emerging economies tend to undergo more rapid economic development than developed nations although this development is frequently accompanied with volatilities and uncertainties. Fourth, developing countries are frequently characterized by high market demand, particularly from middle-class clients. Fifth, all the countries have different size measured by market capitalization, and income per head among others; for instance, Mexico and the BRICS are large while some countries from Asia-Pacific are smaller in size. Lastly, different countries adopt different economic policies; for example, economies like China, Indonesia and India adopt administrative, monetary and fiscal policies while others adopt monetary and fiscal policies to manage their economies (Luo, 2002). In the following section we shall briefly discuss in general the various common forms of financing that exist in many countries, since this knowledge will form the foundation of later discussion on the concept of syndicated loan market itself.

Methods of financing

Entrepreneurial finance

This type of financing starts with the commencements of the need to use personal financing such as personal savings and money borrowed from family and friends and makes up a significant financial pool of most countries particularly in developing nations. Unfortunately, the unavailability of data on financial operations of new businesses operating in developing countries makes it hard to evaluate how investment is carried out, and thereby the extent that this form of financing is used (Boot and Thakor, 1993).

In most situations, more efforts are being put to offer a number of formal financial institutional structures that will fund the start-ups, this mostly entail government’s efforts to help entrepreneurial funding like the small enterprise administration in US. Several developing nations have developed same programs with support from quasi-governmental that aims at supporting entrepreneurs financially (Boot and Thakor, 1993).

Lastly, credit offers a vital source of the unofficial intercompany funding that is specifically important to small companies; the trade credit is also important in the developed nations but a frequently disregarded source of funding. When channelled from big companies to small companies, it offers the latter the working capital needed as well as facilitates them to deal with financial hardships. The trade credit usually has bad reputation in developing nations because it frequently leads to intercompany arrears and budget constraints (Boot and Thakor, 1993).

Bank lending

Firms turn to the financial institutions as they grow for funding requirements, beginning with the banks. In a number of developing nations, bank financing to businesses has remained principally a mere expansion of government soft financing to public sector (Boot and Thakor, 1993); thus, the banks accrued huge portfolios of loans that were not performing and needed broad recapitalization. However, bank financing in most developing countries sponsored by the government has ended and most of the banks in many nations have privatized productively. In these nations, bank financing to firms is on business terms utilizing suitable credit standards (Dennis, 2000). Nonetheless, there is propensity to anticipate banks to put more effort than they may practically achieve.

Several developed nations capital market funding is also important just like bank funding since banks are still vital institutions because of banks’ credit ratings and their associations with other firms and lending markets (Dennis, 2000).

Capital market funding

After utilizing other sources of finance the firm may opt to access the capital market; the activities of capital market can begin at earlier levels of company’s enhancement during venture capital. Primarily, institutions offer start-up finance to entrepreneurs who do not have the track record required for bank financing.

A completely developed firm is more likely to go public to obtain funding but most infrastructure of the financial sector and financial institutions have been sluggish to grow in most developing nations even though more complex institutions exist or appear to be in existence. But equity markets are widespread in developing nations (Boot and Thakor, 1993).

This field of funding relates to sources of funding normally extended to a company as it expands from start-up to being a publicly held firm as well as to enhancement and maturation of financial institutions of the developing nation. This is even though the developing nations are not equivalent to conventional developed economies given that their pre-evolution environment varies considerably from those of other emerging nation’s environment. Numerous inherited business sectors have firms, which are extremely developed to battle in the international markets by selling superlative products; many of them have very unequal development pockets throughout their sectors. All of them have financial institutions that are underdeveloped compared to the economic development level of the country they do business in. Simultaneously, these economies have financial institutions having several traits similar to institutions in the industrialized economies. Additionally, the transformation process resulted to the rapid enhancement of other financial institutions which were forced into eminence by privatization procedures in many developing nations.

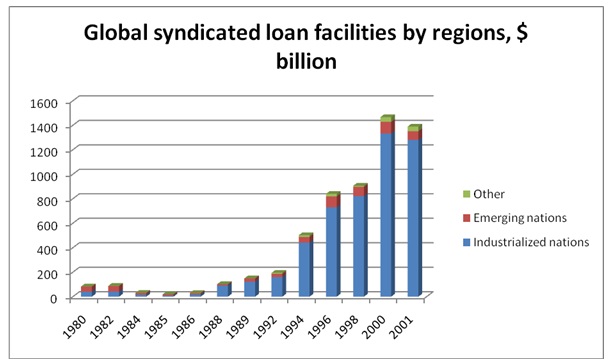

The management of global bank lending

Management of global banks and changing function tend to be the main aspects behind cross-border lending by banks. Three major stylized specifics concerning the changes in the global banking seem to be significant for the cross-border lending in the developing nations in the past two decades. First, the foreign banks turned out to be the main participants in the local financial sector of many developing nations (Gyntelberg, McGuire and Goetz, 2009). The bank lending by overseas banks’ affiliates at the year ending 2008 for instance had totaled $1.5 trillion in the developing countries of Asia, $0.8 trillion in Latin America, and $0.9 trillion in developing countries in Europe (McGuire and Tarashev, 2008). Secondly, the development of global banks mostly embraced the improved form of local currency loan provision of the domestic members, particularly in the Latin America.

This meant that cross-country lending by banks turned out to be comparatively less significant in those areas (McGuire and Tarashev, 2008). In real sense however, most of those branches operated as domestic banks but with overseas ownership. In addition, currency disparities were restricted in those areas as well. The provision of loan through the local currency by domestic members propose that when considering the function of the global banks away from cross-country lending, a broader perspective requires to be incorporated as well. Although to some extent exceptionally developing countries in Europe mostly depended on the cross-country lending. Such dependence, particularly on the cross-country wholesale financing exposed those banks to sudden stops risks. The exposure was made worse by the overseas currency credits which further contributed to the currency discrepancies (Gyntelberg et al, 2009).

Lastly, two diverse models of global banking have surfaced, building considerable dissimilarity in cross-country bank loan provision and the bank’s behaviour (McGuire and Tarashev, 2008). Conversely, a number of global banks centralized management of liquidity, lending decisions and capital structure, connecting developing nation’s operations more directly to the total lending bank’s decisions. Alternatively, other banks decentralized these operations, administering liquidity individually (Takats, 2009).

Such global banking structure may have been significant in easing credit crunch or aggravating it. Some facts from Mexico propose that banks that are decentralized offer more firm lending during credit crunch scenarios. The Bank Negara Malaysia noted that needing overseas banks to be domestically incorporated as well as committing assets domestically limited any contagion effects (Takats, 2009). Therefore, it is probable that distressed banks that are centralized could not offer sufficient lending to comparatively robust developing markets. Although centralized banks in some cases might be able to offer support for sternly distressed markets through steadily distributing liquidity. These aspects may have reformed developing nation’s experience at the time of crisis; additionally, the foreign bank’s size, the loan provision channels that they opted for and their management structures may have impacted on the manner in which financial crisis impacted lending in the developing markets (Takats, 2009).

Syndicated loan

This section will discuss the syndicated loan market development, how the market operates as well as how it is structured. Syndicated loan is normally offered by a group of financial institutions such as banks to borrowers like the firms or the government. Syndicated loans are traded publicly and they allow banks to share the risk involved without having to disclose or market the instruments like the bond issuers therefore these types of loans include both features of relationship loan provision and debt (Allen, 1990). Syndicated loans are considerable source of global funding since global syndicated credit facilities accounts for at least a third of the entire global funding, together with bonds, equity issues and commercial paper (Robinson, 1996).

This unique aspect presents a historical analysis of advancement of this ever-important international market and portrays its operation, focusing on contributors, pricing systems, secondary trading as well as principal origination; in addition, it measures its geographical integration degree (Allen, 1990). Also, the largest banks in Europe and US tend to instigate loans for the emerging nation’s borrowers and distribute them to the local banks. The European banks appear to have enlarged pan-European loan provisions and now cover financing outside the European region (Coffey, 2000); to understand this, there is need to discuss the market development.

Market Development

The development of the syndicated lending may be categorized into three stages; loan syndications developed first in the 70s as a superior business (Coffey, 2000). The repayment hardship experienced by most developing countries that had borrowed loans in the 80s led to the streamlining of the Mexican loan into Brady bonds in the year 1989 (Coffey, 2000). The transformation procedure triggered a move in the developing countries borrowing pattern toward bond funding, leading to a reduction in the syndicated lending trade. But in developed countries syndicated lending increased; since 1990s for instance the syndicated loan market has experienced a renewal and has increasingly turned out to be the largest market for corporate finance in the US. In fact, in 1990s it was the major source of lenders underwriting income (Robinson, 1996).

The first stage of the development started in 1970s, and from 1971 to 1982, the medium range syndicated credits were broadly utilized to direct foreign assets to the emerging nations in Asia, Africa and particularly Latin America (Finnerty, 1996). The syndicated loans allowed the financial institutions that were small in size to obtain developing nation’s experience without instituting any local existence. Syndicated loans to developing nation’s borrowers advanced from little amounts in first quarters of 1970s to $46,000 million in the year 1982, progressively relocating mutual lending (Finnerty, 1996).

Loan provision suddenly stopped in the third quarter of the year 1982, following Mexico suspension of interest repayments of its sovereign loan, then other economies followed suit including Argentina, Brazil, Philippines and Venezuela (Finnerty, 1996). The lending capacity attained its lowest peak at $9,000 million in the year 1985 while in the year 1987 Citibank recorded a huge percentage of its developing nations’ credits and some huge banks in the US banks followed later (Finnerty, 1996).

This shift catalyzed the plan negotiation commenced by the US Treasury, Mr. Brandy, which made lenders to swap their developing nations syndicated credits for the eponymous credit securities (Finnerty, 1996). Thus, Brady bonds rate of interest repayments primarily benefited from diverging collateralization degrees on the US Treasury (Gadanecz, 2004).

Brady plan offered a new drive to the market of syndicated credit; on the first quarter of 1990s, the banks that had experienced serious losses in debt crunch began applying more complex risk charging to the syndicated lending. They also started to make broad covenants use that affected the companies’ ratings and debt servicing (Finnerty, 1996). Whilst banks turned out to be more complicated, more data turned out to be accessible on the loan performance because of the advancement of the secondary market that steadily drew other financial institutions such as insurance firms and pension funds (Rousseau and Paul 2000).

While the unfunded and guaranteed risk shift systems like synthetic securitization made it easy for the banks to acquire security against risk of credit and at the same time keep the credit on the statement of financial position.

The beginning of these risk management systems made it easy for broad range of financial institutions to provide loans to the market, together with those who’s lending strategies as well as loan limits may not have permitted them to take part previously. More significantly, borrowers from developing countries as well as companies in developed nations increased the appetite for syndicated credits since they viewed these loans to be essential, elastic because they could be approved rapidly and critical to harmonization of other external funding sources like bonds and equities (Rousseau and Paul 2000). Therefore, these advancements led to the growth of syndicated lending ever since 1990s up to now because in 2003, the total loan signed totaled $1,600 billion which was in excess of 1993 amount (Rousseau and Paul 2000).

Developing markets borrowers and developed nations comparable have tapped the market with emerging nations recording 16% of trade while developed countries (Europe and US) shares the remaining 74% in half. In Japan syndicated lending market is developing but currently it makes up only a small proportion of the total local bank loan provision and it’s not as a result of conventional significance of major banks that credit the companies (Rousseau and Paul 2000).

Syndicated loans have in effect turned out to be a very important financial source in such a way that the global market report approximates that one-third of worldwide funding utilizes equity, commercial paper and bond (Rousseau and Paul 2000). Current figures indicate that the percentage of acquisition, mergers and buyout-linked credits were 13% of total capacity in the year 2003, compared to the 7% in the year 1993 (Rousseau and Paul 2000). Subsequently, the increase in privatizations in developing nations in firms that deals with utilities, mining firms, transportation and banks over the recent past has began to be more independent and are currently the main borrowers in these areas (International Finance Corporation, 1998).

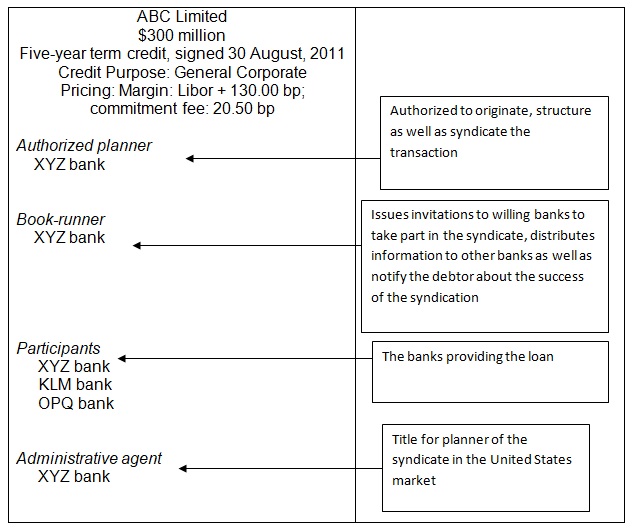

A crossbreed between dis-intermediated debt and associations lending

This section will deal with how the syndication process is carried out and who are normally involved. In order to carry out the syndication process two or more financial institutions must jointly agree to give loan to the borrower; thus, each member in a syndicate has a different allege on the borrower, though there is only one agreement (Rousseau and Paul 2000). The lenders may be in two groups the first group comprises of “superior syndicate members”; these superior banks are employed by the creditor to draw together the banks syndicate, which is prepared to offer the loan at the conditions specified by the credit (Rousseau and Paul 2000). The syndicate is created around the planners who maintain a percentage of the credit and seek for junior partakers, while the small banks form the second group of lenders and are normally partakers or manager (International Finance Corporation, 1998).

The small banks’ identity and number may differ based on size, difficulty as well as pricing of credit and willingness of debtor to raise the array of its relationship banking. Therefore, syndicated loans lie someplace between association loans as well as dis-intermediated debt.

Table 1 indicates in ascending order the banks that may take part in uncomplicated syndicate structure in order to provide credit to ABC Limited (Gadanecz, 2004).

Superior banks might have a number of motives for planning syndication. This can be a way of keeping away unnecessary single-name disclosures that complies with legal limits on the risk focus whilst sustaining an association with the debtor; or it may be a way of earning fees that assists in diversifying their revenue (Rousseau and Paul 2000). Generally, banks have to plan on how to provide syndicated credit in order to meet the debtor’s requirements for credit without having to be exposed to risks like credit or market risks (Rousseau and Paul, 2000).

For smaller banks taking part in syndicated credit may be beneficial for a number of reasons; these financial institutions may be inspired by a need for origination capacity in specific forms of geographical regions, transactions, industries or the need to reduce the cost of origination (Rousseau and Paul 2000). Whilst small banks that are participating normally receive only a margin without fees, they also expect that they will earn a reward in terms of profit for their participation through corporate finance, advisory work or treasury management (International Finance Corporation, 1998). Therefore, the banks must decide on how to price the syndication process which is discussed in the following section.

Pricing structures

In addition to receiving spread above the floating rate yardstick commonly referred as libor on the fraction of the credit that is given, banks involved in implementing syndicates earn a number of various fees as their commissions (Rousseau and Paul 2000). The planner and the members of the syndicate normally receive several types of fees in advance in return for placing the transaction together frequently termed as arrangement or praecipuum (Rousseau and Paul 2000). Those who underwrite the deal receive the underwriting fee because of assuring the accessibility of finances. Other partakers may anticipate earning the participation fee because of approving to connect with the facility although the real fee size varies with commitment size (Rousseau and Paul 2000). The small banks in the syndicate normally receive only the spread over and above the reference return. Syndicate members may earn a yearly facility or commitment fee relative to the member’s commitment once the loan is instituted and given (Rousseau and Paul 2000).

Once the loan is given, the debtor will have to give yearly utilization fee on the loan withdrawn and the bank acting as the agent receives agency fee that is normally paid yearly to cater for administration costs. Table 1 above offers a case of uncomplicated fee structure in which ABC Limited has to disburse the commitment fee together with the margin; fees and spreads size varies depending on various aspects. Fees are actually less important for Libor-based loans than for Euribor-based loans (Gadanecz, 2004). Furthermore, the developed market debtors allocation of fees in aggregate loan cost is more than in the developing nation’s ones. Possibly this may be linked to industrial composition of debtors in these sectors.

Those entities that are non-sovereign in the developed nations may be interested in tax or the market revelation motives so as to earn a huge percentage of total cost of loan in terms of fees instead of spreads. This is despite the fact that the aggregate cost of the loans given to developing market debtors is superior than facilities provided to the developed nations, also the commitment fees on the facilities offered to developing economies vary widely. In total, creditors appear to ask for extra compensation for superior and added credit risk in the developing world in terms of fees and spreads, meaning that lenders ask for more from the borrowers apart from fees and spreads in exchange for taking risks. Collateral, guarantees and credit covenants provide the likelihood of clearly relating pricing to the firm events; thus, guarantees and collateralization are more frequently utilized in developing market debtors (Figure 3) whilst covenants are widely utilized for debtors in the developed nations (Gadanecz, 2004).

Secondary and primary markets: transferring versus sharing risk

This section of the paper will discuss the secondary and primary markets of the syndicated loan in which commercial banks have dominated the loan primary market at the junior finances provider and senior planner levels. The investments banks have benefited since they are experts in underwriting as well as in increasing incorporation of bank loan provisions and dis-intermediated loan market in planning for loan syndications. In addition to the superior contribution of the investment banks, multilateral agencies like Inter-American Development Bank or IFC are also participating (International Finance Corporation, 1998).

Syndicated loans are more and more transacted on the secondary markets. Document standardization for credit transaction established by the professional bodies like the Asia Pacific Loan Market Association and Loan Market Association, have added to enhanced liquidity on the markets (International Finance Corporation, 1998). A gauge of tradability of credits on this market is the occurrence of moveable clauses that enables the shift of claim to a different lender (International Finance Corporation, 1998). For instance, the United States market has produced the uppermost share of moveable credits, 25% of aggregate credits from the year 1993 to 2003 followed by European market with 10% (Rousseau and Paul 2000). The market is normally supposed to comprise of three sections such as leveraged, distressed and near par (Rousseau and Paul 2000). The distressed section has the most liquidity and credits to the huge firm debtors also appear to be vigorously traded (Rousseau and Paul 2000).

Partakers in secondary market may be split into three groups: active traders, market-makers and occasional investors or sellers (Gadanecz, 2004). Market-makers are normally huge investment and commercial banks putting their capital or assets to create liquidity as well as take complete positions. Financial institutions actively involved in the loan origination in the primary market are at an advantage in transacting on secondary loan market because of “skills gained in comprehending and assessing loan documentation” (Gadanecz, 2004). But commercial and investment banks are the most active traders as well as expert loan traders and the so-termed “venture finances”; non-financial firms and institutional investors like insurance firms also transact, though to a lesser degree (Gadanecz, 2004).

As financial institutions institute the credit management divisions, there tends to be a growing awareness paid to comparative trade values; these removes inconsistencies in return or yield involving credit and other financial instruments like equities, bonds and credit derivatives. Finally, the presence of irregular partakers is felt on the market as sellers of credits to manage the facility on their statement of financial position or like investors who acquire and hold positions. Risk’s sellers can take away credits from their statement of financial positions so as to meet legal limits, liquidity and hedge risk or handle their risk exposure. For instance, some of the US banks have outstanding credit commitments and are normally controlled by Federal Reserve Board as a result the banks have been successful in distributing the syndicated loans as shown in the table below (Gadanecz, 2004). The small size borrowers transfer risks to their country or sector because they participate in the secondary market and their small size cannot allow them to participate in the primary market (Gadanecz, 2004).

Chart 2: US Syndicated loans. Source: Gadanecz, 2004.

Increasing secondary volume traded remains comparatively reserved against aggregate volume of syndicate loans planned on primary loan market. The US has the largest secondary loan market for the loan trading that has a trading volume of $145,000 million in the year 2003 which is equal to 19% of emerging originations on the prime market in that particular year and equal to 9% of the outstanding syndicated credit obligations (Gadanecz, 2004). In Europe, the trading volume totalled $46,000 million in the year 2003, increasing by over 50% compared to year 2002.

In US and Europe distressed credits continued to comprise a large portion of aggregate secondary transaction (Gadanecz, 2004). Admittedly, to a certain degree this mirrors superior stages of firm distress in the European region, although as investment grade section grows it pinpoints to sustained investor’s appetite as well as the market’s advanced capability to take in a huge allocation of below-par-loans (Gadanecz, 2004). In the region of Asia-Pacific, secondary capacities still represent a small proportion of those in Europe and US with at least seven banks operating devoted desks in the Hong Kong SAR without non-bank partakers (Gadanecz, 2004). In 1998, the Asian secondary market was extremely active because huge credit portfolios were exchanged as a result of what the banks in Japan termed as “distressed credit portfolios” (Gadanecz, 2004). As a result, dealing was more unresponsive in following years, though banks’ interest seems to have presently been revived by the resultant prices of credits that have declined below those of guaranteed loan bonds and obligations (Gadanecz, 2004).

Secondary Prices for Emerging Market Loans

This section will describe the secondary prices that emerged in 1980s as a result of Brady plan. The concessions between the borrower and lender countries in the 1980s global debt crisis was a sequence of loan conversion plans usually known as “Brady Plan” (Ramcharran, 1999). A number of significant alternatives in this plan were first, translation of the existing debt into new bonds that can be traded with assurance fastened and put on the market at a markdown (Ramcharran, 1999). Secondly, the translation of the debt into bonds with comparatively reduced return, third, the preservation of the existing debt though with new assurances as well as new lending for in so far as 25% of risk value is concerned (Petersen and Rajan, 1995). Lastly, access to extra capital provisional on the market-oriented financial reform intended to raise the efficiency as well as competitiveness of the borrower countries (Petersen and Rajan, 1995).

This Brady plan saved $3,800 million in Mexico in one year in loan-servicing repayments and was later implemented by Uruguay and Venezuela (Mian, 2006). However, arguments existed amongst academicians, government officials and bankers relating to the precedence and somewhat the efficacy of these alternatives. The idea was to decrease the banks’ risk exposure, increase their creditworthiness as well as the debt-serving capability of borrower countries and finally decrease debt-serving commitments of these countries. Indeed, the debt translation policies promoted a market that was active for the developing nation’s sovereign loans (Mian, 2006). This market has grown enormously in the latest years and has turned out to be very liquid as result of the rising number of partakers, a broad range of loan reduction alternatives and a number of legal changes impacting on the banks.

The lending loss impacted the market price considerably in excess of basics in the borrower countries. Recently the prices of the debt have been determined strongly by the market forces as a result of the market growth in terms of trading volume and liquidity. Also the most significant influence on the present prices is actually the financial development policies of the borrower countries as well as their capability and readiness to service loan repayments (Mian, 2006).

As a result the emerging nation’s loan was among the greatest investments in the year 1996; earning 24% which was superior to the US bonds and stocks (Mian, 2004). The developing countries debt revaluation was characterized by: first, improved economic performance, second, increasing confidence in that the governments were dedicated to repay the loan and lastly, numerous investments emerging from various sources taking in investors that invested in mutual funds (Mian, 2004). Since the developing countries’ loan shows market consensus concerning present and anticipated cash flows from these debts and the possibility of repudiating or rescheduling these debts, many countries with debt are still being influenced by economic impact of the loan overhang issue and therefore still bargaining with global lending creditors and institutions for loan amnesty (Mian, 2004). Further to this, the following section will deal with the loan market in the developing economies.

Market for emerging nation’s loan and Brady plan

The IMF played a significant role during credit crisis by providing a huge amount of debt to the borrower countries. Whilst the borrower countries and the IMF were searching for new cash, banks were searching for a solution to the crisis in order to decrease the risk exposure (Khanna and Palepu, 1999). During the first stage of the credit crisis, from 1982 to 1987 the borrower nations and commercial banks agreed on processes to reorganize some of the loans (Khanna and Palepu, 1999). The accords on terms of reorganization were contentious because the cost extent and benefits to debtors as well as creditors varied. By 1986 the banks advanced some beneficial approaches for loan diminution in a deliberate manner that included exit bonds, loan for equity exchange and loan buyback among others. The incentives for most of these strategies were suggestions by Brady and Baker, the US Secretaries at the time (Khanna and Palepu, 1999).

In the years to follow the credit crisis suffered a decline as was the case in 1987 when a suspension on more interest reimbursements to banks was announced by Brazil. This announcement prompted Citibank, the main lender to declare a debt loss reserve amounting to $3,000 million against developing nations’ debt risk exposure; consequently, other main banks made the same decision and by 1989 the global financial society made a decision to completely implement Brady plan (Khanna and Palepu, 1999). Fundamental to this Brady plan was formal support of loan decrease policies provisional on the execution of the structural financial reforms (Ramcharran, 1999).

Particularly, the Brady plan aimed to attain several objectives; first, to support the market-oriented financial reforms to develop efficiency and competitiveness (Ratha and Shaw, 2007). Secondly, translate existing loan into Brady bonds, third, encourage borrower countries to repurchase a number of their formal loan from the World Bank and IMF to offer motivation for extra private debt (Ramcharran, 1999). Fourth, to attract capital from abroad in form of equity and finally to reduce the bank’s risk exposure and enhance the developing nations credit ratings (Ramcharran, 1999).

A milestone in crisis history took place in the year 1985 at the time when Chile bargained its first loan for the equity swap; this plan made it possible for lenders to decrease a proportion of their loan in trade for equity in the domestic firms. International firms and investors who were speculative took the advantage of the Brady plan to raise the Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) in these nations. The plan assisted in privatization part of market-oriented structural change plan that was approved by IMF. Ineffective government-owned public utility firms were privatized first followed later by banks, as was the case in Mexico (Institutional Shareholders’ Committee, 2002). Active secondary loan market emerged from the loan translation plans for the developing nations’ loan with partakers including huge investment and commercial banks, wealthy investors and MNC. As a result, about $132,000 million of the debt from the developing nations have been translated into bonds in the plan (Ramcharran, 1999).

Recently, this market has developed steadily based on the liquidity and the trading volume, in the year 1995 the bank’s sovereign debts were approximated at $350,000 million of which $250,000 million was from the secondary market (Ramcharran, 1999). An important feature is the recognition of determinants of the debt prices of the developing nations; primarily, the trading was experiencing depressed prices mostly because of legal factors that affected the US banks. The capital restriction discouraged US banks from putting on the market huge proportions of their developing countries’ credit while the main banks in Europe were actively selling theirs. Most of the trading comprised of the debt-for-debt exchange, though with the start of the debt-for-equity swaps the US banks turned out to be active partakers (Ramcharran, 1999).

The degree to which financial institutions have written-down the loan in their balance sheet strongly affected the supply situations and hence prices. In the early years of 1990s, prices turned out to be more market established mostly because the governments of the lending banks amended the tax structures and regulations while various loan decrease schemes significantly raised the level of the consumer market participants, therefore improving liquidity. Such prices can have a major influence especially to the policies of borrowing nations themselves based on their capability and readiness to repay loan and execute the policies of the economic growth (Ramcharran, 1999). For this to be effective banks must have systems that operate effectively; consequently, the following section will discuss how this can be dealt with and attained.

Principles of effective banking in developing countries

In the planned country cash acted as a unit of account and took part in a limited role as a medium of exchange. The two-track financial sector was upheld in which family units used money for transactions whereas transactions in the state sector in addition to those between state-possessed production enterprises involved no monetary payment (Simons,1993). The compliance for cash was sustained by a banking sector in which the mono-central bank was an archive for record entity for transactions between production units. In many economies, banks work independently from the central bank and carries out specific roles where a United Kingdom saving bank with a broad branch network was accountable for gathering family unit deposits and a foreign trade bank handled all transactions involving foreign legal tender (Zuckerman and Sapsford, 2001). But risk management and credit evaluation were inappropriate, so these proficiencies were never developed locally as foreign banks’ workers and those at the central bank engaged in worldwide financial arrangement as well as analysed overseas exchange risk but in an elementary way (Preece and Mullineaux, 1996).

The first step in banking sector reform in all economies was structural which involved the formation of a two-tier system with retail activities and commercial that was carved out of the portfolio of the mono-central bank. The new central bank was alleged with pursuing fiscal policy, together with exchange rate and was accountable for the management and supervision of the nascent banking sectors (Arestis and Demetriades, 1999). The commercial tier comprised of the recently made commercial banks, the de novo private banks, specialty banks and foreign banks (Narayanan, Rangan and Rangan, 2004). But the bank in general has three vital operations that is disbursements, recording keeping, settlement as well as the well-organized intermediation between investors and savers (Megginson, Poulsen and Sinkey, 1995).

While the banks in the emerging nations are not very well developed though with some exceptions of countries such as Slovak and Czech Republic which had a ratio of M2 to the GDP of 65% and 75% in the year 1999 respectively (Harjoto, Mullineaux and Yi, 2006). Poland and Hungary had a ratio of approximately 45% just like Estonia and Croatia who decreased their inflation rate (Arnone et al, 2006). The ratio of monetization in some other countries such as former Soviet Union was normally 25% which was comparable to developing countries (Megginson et al, 1995).

Thus, for any banking sector to be efficient two pillars must be in existence that include financial strength and independence. In terms of independence, banks should have a governance structure intended to promote effective intermediation as well as a legal system for effectively managing the existing banks in addition to licensing practically new banks. The major objectives of the legal agency are to sustain the steadiness of the system of payments and secure household savings (Arnone et al, 2006).

This made many banks in the developing nations to be acquired because of fairly small banking market, so just a few local banks were feasible, and this led to emergence of bankrupt banks that triggered the authorities’ action in coercing mergers and acquisitions with bigger banks. This sparked the big United Kingdom owned banks to take-over the failing smaller banks that had deteriorating balance sheets (Bird, Graham and Rowlands, 1997). The reduction of small banks was needed to downsize banking sectors after extreme entry and the means to attain this was to coerce small insolvent banks to merge with bigger feeble banks making the acquirers even weaker (Davies, 2001). Alternatively, the other option was to inflict stricter licensing requirements on banks during registration so as to regulate the industry and avoid unhealthy competition (Bird et al, 1997).

Therefore, as a core future business banking industry must provide high quality products and services to commercial and retail consumers and must fulfil the short terms and long terms expectations of profitable commercial clientele in order to increase its future income (Bird et al, 1997). In developing economies the license value of banks has frequently been related to short terms and rent seeking activities, so when designing policies the regulator must pay much attention to the license value of banks (Arnone et al, 2006). For these banks to be effective corporate governance must be incorporated into the system. Thus the following section will discuss will deal the corporate governance.

Corporate governance

In the year 1992, the corporate governance report on the aspects of finance by Cadbury Committee was published and led to the establishment of codes for the corporate governance in economies like UK, India and Russia (Cadbury, 1992). This committee was instituted after the collapse of several high profile businesses in UK that had traumatized the market confidence (Adrian, 1992). In the year 2001, the fall of Enron sent ripples throughout the economy and caused ripples in US. As a consequence the Enron downfall and several other scandals that are of high profile from the time when it occurred made the US to re-evaluate the country’s structures of the corporate governance as well as provisions so as to enhance the same and hence avoid another Enron situation (CombinedCode, 1998). The European region likewise is enhancing legislation and principles to develop corporate governance because of Parmalat and Royal Ahold scandals that sparked reforms in governance (CombinedCode, 1998). Likewise in the European region governments are enhancing legislation and principles to develop corporate governance because of Parmalat and Royal Ahold scandals that sparked reforms in governance (High Level Group of Company Law Experts, 2002).

Corporate governance is defined by OECD (1999) as “a set of relationships between a company’s board, its shareholders and stakeholders”. Additionally, corporate governance entails providing “the structure through which the objectives of the company are set and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance are determined” OECD (1999). This definition clearly shows that corporate governance is more concerned with external features like the association with stakeholders and shareholders as well as internal features of the firm like board structure and internal controls. Additionally, it also provides the framework through which firm’s aims may be laid down, supervised and attained.

Various studies describe corporate governance to also comprise the means for transforming management and ownership as well as inducements in the capital markets that transform and determine administrative conduct. These inducements are in accordance with the requirements for external financing from public debt, equity markets and banks (CombinedCode, 1998). The accessibility of external financing sources, which is the main corporate governance aspect, was evidently cherished by Arthur Levitt (former US SEC chairman) when he stated

If a country does not have a reputation for strong corporate governance

practices, capital will flow elsewhere. If investors are not confident with the

level of disclosure, capital will flow elsewhere. If a country opts for lax

accounting and reporting standards, capital will flow elsewhere. All enterprises

in that country suffer the consequences (Cgdc.org.mn, 2011).

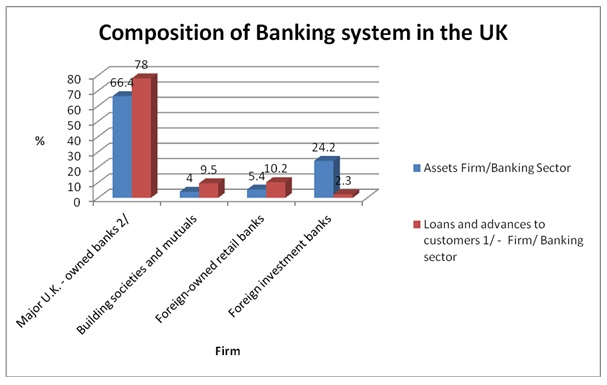

The emergence of corporate governance was driven by several main drivers that included the fall down of well-known firms, both in non-financial and financial sectors like BCCI, Polly and Barings resulting to improved prominence on regulatory to uphold assets (CombinedCode, 2003). Secondly, ownership of shares changed, specifically in the UK and US resulting to a superior focus of the ownership of shares to the institutional investors like the insurance firms and pension funds. For instance, the UK’s institutional investors possess approximately 80% of UK’s stock market while the US has a lower figure compared to UK, though this group of investors (institutional) controls the market (CombinedCode, 2003).

Thirdly, institutional investors seek to spread their portfolio by increasing overseas investments. Fourth, with technology development in the communication industry and in general market, facts can be circulated more broadly and rapidly, in addition to institutional investors communicating internationally with one another and creating universal viewpoints on the main features of the investments like corporate governance 9Franks and Sussman, 2000). Fifth, corporate governance has become essential in assisting to offer assurance in those firms and also in attaining external financing at the least cost possible to firms seeking external finances, whether it’s from local or global sources (CombinedCode, 2003). Lastly, a well-designed corporate governance system promotes stock market confidence in a country and to the economy in general, thereby building an investment environment that is more attractive (CombinedCode, 2003).

Based on this discussion it is apparent that the financial sector plays an integral function on the concept of corporate governance. The banks in the European Union by acting as creditors to the SMEs and the “Mittelstand” firms have conventionally played a key function in corporate governance through cross-shareholdings, equity-holdings as well as mutual wide membership (Capiro and Levine, 2002). On the contrary, the banks in the UK are not the main shareholders; as an alternative, mutual funds and pension insurance are highly enhanced mirroring the most significant role previously played by UK’s capital market (ESFRC, 2002).

However, the owners of the firms have become activist and presently this has started to materialize as an important strength in the UK and these owners have undertaken a number of functions as “strategic investors” in the Continental Europe (European Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee, 2002). Previously, the risk of the hostile takeover by Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) has been viewed as the major controlling UK force. The advance in the Continental Europe was to administer reformation through friendly bargaining amongst the strategic shareholders with regulating ownership-stakes in companies and at the same time evade challenging “mergers” and expensive bankruptcies (Franks and Sussman, 2000). Regulation cannot be openly put at risk in the marketplace because of takeover suspicion of voting-rights for varying share classes such as the strategic shareholders who are the “insiders” within the firms and the institutional shareholders who have conventionally been the “outsiders” (Greenbury, 1995: Khanna and Palepu, 1999). Therefore, the codes of corporate governance in UK may be considered as the mechanisms of transforming “outsiders” to “insiders” in the Continental Europe (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 1999).

The UK financial market was integrated and the US and Japan adopted the European style common banking and bancassurance since the capital markets rose significantly in the Continental Europe triggered by industry privatization and the pensions (Adrian, 1992). After the market integration pension, mutual funds and insurance increased in importance since they became institutional shareholders as opposed to strategic shareholders with close relation to the huge collective banks but the UK and US disputed the feasibility of collective banking model due to divergence of interest in the investment bank (Hampel, 1998). In addition, specific problems such as research independence meant to benefit the shareholders and also the likelihood that shares may be sold cheaply to those customers who may well acquire other bank services in future was a concern. For instance, commercial banks sell their loans and credit lines cheaply mostly to customers who are motivated to acquire more complicated investment services for banks emerging from salesperson (ISC, 2002). It is uncertain whether cautious utilization of the “Chinese walls” as well as independently capitalized branches will be sufficient, or whether possible conflicts must be done away with by extra branch and root reform since the US experiences have shown that divergences of interest are simply the photocopy of synergies in multinational financial institutions (ISC, 2002).

The financial sector should be effective so as to carry out the corporate governance. This sector is highly regulated given that it has several fiduciary duties that are involved and its existence is based on the information variation and the scale of production. Thus, the institution of effective system of corporate governance needs the institution of competitive and effective financial sector dependent on supervision and regulation to safeguard the economy and broad community from methodical failures (Lin, 2008). The main aim of competition in the financial industry is to decrease the extent for divergence, but this aim may contradict the supervision and regulation in attaining firmness leading to decreased systematic risk. The execution of Basel II Capital sufficient structure is to raise awareness in banking as well as financial industry in general and in case the rivalry is decreased in the industry, interest divergence is destabilized significantly (ISC, 2002).

The collapse of the Enron led to the debate on the extent to which the market will determine the behaviour of the firms. More exposure of information, as proposed by codes of corporate governance for the companies and the Basel II for the banks, is helpful if information exposed is to be reliable and accurate (Laeven and Valencia, 2008). Auditing and accounting standards together with the disclosure rules generally influence reliability and accuracy, but if these rules do not conform to banks and corporation inducements to disclose this will lead to questioning of the effectiveness of the rules (Mallin, 1994). Information inequality creates an advantage to make use of information not available to others and this motivates some market participants who take the initiative to decrease the gap of information by signaling and disclosing instruments (Ayuso and Blanco, 2001).

A bank which is specifically sensible in risk taking as well as contractual implementation may for instance like their shareholders to know this; conversely, there are constantly some financial institutions and companies that take advantage of information variation since they may result to insider trading or charging high for shares issued (Mallin, 2004). The team of managerial position would like to evade information on their actions being disclosed. But in a competitive industry the firms with superior quality have an inducement to assist in disclosing the real nature of the one not willing to disclose information. Therefore, in a non-competitive sector the disclosure rules may be very important. If these rules are contradictory with inducements to disclose information of banks and firms of superior quality, all participants in the market have the inducement to restrict disclosure as they may be dishonest (International Monetary Fund, 2008).

Generally, there is etiquette to reveal information in an obscured way but this can be avoided if the financial industry assures superior corporate governance through the creation of competition among companies in the capital markets. Competition in the capital market can effectively distribute capital leading to portfolio amendments and re-distribution of the capital (Greenbury, 1995).

The internationalization of the financial markets may lead to efficacy in the financial institutions due to competition in the capital market. But internationalization has been criticized by environmentalist and anti-poverty activists therefore, raising new challenges to corporate governance as well as to institutional investors’ responsibilities (ISC, 2002). For instance, in the US and UK in 1990s, socially responsible or ethical investments finances attracted potential investors ready to take risks if remunerated by extra socially responsible or environmentally conscious investment. In most cases the performance of such funds was to a certain degree less diverse from the mainstream finances throughout the long-standing upswing of the stock market (Mallin, 2004). The stock market upswing promoted firms to be more attentive to the CSR and environmental problems, resulting to use of indices in ranking of firms based on their performance within these non-financial fields, and in other situation they were based on financial auditing, environmental and social performance. In reality UK‘s Pension Law needed pension funds to verify their Social Responsible Investment plan. The government of the UK requires all institutional shareholders to declare their policies of investment as well as their rules of voting at Annual General Meeting (AGM) (KPMG, 2005).

In the past two decades, most governments from many countries in the world started utilizing prudential directive as an element of the process of reform in the financial industry (Arun and Turner, 2003). Prudential directive or regulations entails financial institutions having to maintain capital comparative to their extent of risk taking, early forewarning systems, bank decision schemes and financial institutions being evaluated on an off-site and on-site basis by the supervisors of the banking sector (International Monetary Fund, 2008). The major aim of the prudential directive is to protect the steadiness of system of finance and also the deposits (Cipe.org, 2002).

The reforms previously executed in emerging nations have been ineffective in protecting the banking sector crises, thus prudential arrangements were effective in nations where corporate governance was efficient (Barth, Caprio and Levine, 2001). The capability of emerging nations to reinforce their prudential control is questionable because of several reasons. First, it is recognized that financial institutions in the emerging nations must have significant superior capital needs than the ones in the developed nations even though most banks in emerging nations find it expensive to increase the amount of the capital (Basel, 1999). Secondly, the emerging nations do not have well trained controllers to evaluate the banks (Boot and Thakor, 1993: Mian, 2004: Mian, 2006). Thirdly, the emerging nation’s supervisory bodies usually do not have political independence that may weaken their capacity to persuade banks to conform to prudential needs and inflict appropriate penalties (Boot and Thakor, 1993). Finally, prudential control fully depends on correct and well-timed accounting information even though most of the emerging nations have accounting rules that are flexible and usually lack information disclosure needs (Institute of International Finance, 2008).

A prudential advance to regulation may normally lead to banks in emerging nations raising capital through equity so as to conform to capital sufficiency norms. Subsequently, before emerging nations deregulate their system of banking, attention must be paid towards quick execution of strong corporate governance instruments so as to secure the shareholders (Capiro and Levine, 2002). But in emerging economies, the institution of sound principles of corporate governance in the banking sector has been partly weighed down by weak disclosures of information needs, dominant owners and poor lawful protection. Additionally, in many emerging nations, the banking sector particularly the private sector is not keen to institute the principles of corporate governance. For instance, in India this issue can be summarized as an opportunity of one group interest over the other firm’s interest within the corporate industry (Muniappan, 2002).

However, in order to build a strong market for syndicated loan for any country the financial sector market must be developed in order to facilitate the running of the lending process by the banks involved in the syndicate. Therefore, developing countries must learn from the developed country’s experiences for this plan of a strong market for syndicate loan to work. Thus, the following section will collect the necessary information that will be used to identify the financial models used in the UK and developing nations. By the end of this analysis, this section will have unearthed the differences between the two types of economies i.e. developed and developing as far as syndicated loan market are concerned. As such this paper will be in a better position to provide recommendation for the same in developing nations.

Methodology

This chapter will discuss how the research was designed and structured; it outlines the approach of the research design and also gives details on how the data was collected, analysed and presented.

Research Design and Approach

The central objective of this research study is to identify and recommend strategies that can be applied to strengthen the syndicated loan market in the developing countries by using UK experiences in the same sector as our point of reference. The study will primarily analyze the collected data using normative comparison in both developed and developing nations banking systems. As such the most appropriate research designs to use will involve a mixture of several approaches which include descriptive design, literature review analytical method and comparative (normative) approach. These are preferred because the study will need to analyze wide range of data and variables, both from developed and developing countries banking industry.

Descriptive design is most appropriate where the objective of the research study is intended to generate answers regarding a particular phenomenon or set of issues and is primarily utilized when answers of what, how and so on are needed. Descriptive research design is also appropriate where the research study intends to investigate a topic that has several issues in an in depth manner inform of a case study as has been the approach in documenting the case of UK syndicated loan market. In this case all the three variables of this research study are concerned with investigation of particular issues and use of descriptive research design will therefore be very appropriate.

Literature review is the second most relevant research design that will be suitable for this research study; in literature review key data of interest is reviewed in order to identify trends and patterns of key variables of interest that the study intends to investigate. In this research study, review of literature sources will be central to this paper since no primary data is expected to be collected; without primary data to analyze secondary sources from literature review will form the basis of this paper. Consequently, since this study will not utilize primary data sources, sampling techniques, identification of population size and use of questionnaires will not be discussed in this study.

Advantages of mixed research design

The benefits of mixed research design utilized in this study are several and include; first, it simplifies the process of data analysis since a researcher is able to analyze data effectively by use of the most suitable research design. Secondly, the use of mixed research design is important in analysis of data that has both aspects of qualitative and quantitative as is the case in this study. Finally, the use of combination of two study designs is particularly helpful when investigating a range of objectives.

Data analysis

This research study will generate both qualitative and quantitative data since the sources of data collected will primarily be from secondary sources such as books, journals, articles and magazines as well from internet sources. Accordingly, the data analysis for this research study will be both qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative data will first be coded and the analysed using descriptive statistics techniques while quantitative data will be analysed by excel to and organized in form of graphs and tables. Once the data has been organized and analysed it would now be easy to identify trends and patterns across various variables of interest, and therefore form the basis for consequent discussion.

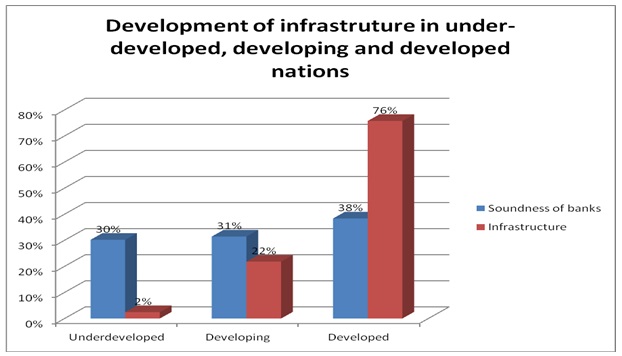

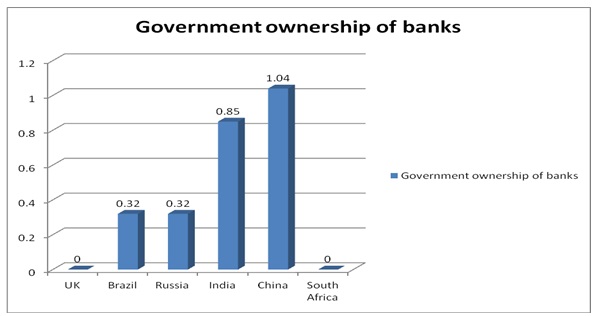

Study variables