Abstract

Germany’s economic landscape is based on a business environment fundamentally different from that of Anglo-Saxon economies like the US and the UK. Merger and Acquisition activities (M&A) offer an interesting academic study in understanding a country’s unique corporate culture. In this dissertation, I have conducted empirical research to understand a specific issue relevant to M&A activities in Germany: agencies – their roles, responsibilities, business costs, and potential conflicts.

Agencies will consist of individuals, shareholders, managers of a firm, employees having stock options, and also institutions like banks – especially in the case of Germany, agencies play a very important role in all M&A transactions. Agency costs are usually documented by executive compensation i.e. financial incentives allotted to top executives of M&A entities which will eventually translate into successful deals worth billions.

In order to tap into this resourceful insight into the complexities of M&A activities which translate into significant wealth for corporations, I have attempted detailed research into the impact of executive compensation on the financial health of merged entities. Around 200 German firms were short-listed for their post-merger financial scenario regarding successful M&A activities. This dissertation consists of agency theories and their empirical verification using statistics (regression analysis).

Executive Summary

Merger and acquisition (M&A) activities present a litmus test for corporations seeking to establish themselves in an increasingly competitive business world. From the trade environment to global suppliers, market, and business culture, M&A activities offer an unprecedented array of challenges and opportunities for firms seeking to increase their market presence using global tactics of expansionism. Germany, at the center of Europe, is considered a highly valuable focus of research when it comes to understanding the true facets of M&A transactions; Germany after all, is the fourth biggest M&A market in the world.

It is been established early on in this study that agencies play a very crucial role in supplementing the desire of corporations to expand their wings in a global marketplace. In order to facilitate these roles, various aspects of agency responsibilities have been clearly outlined in the research. The biggest and most important agency cost identified for my specific research is a preponderance of executive costs as a direct function of various output parameters e.g. financial ratios such as profitability, liquidity, debt ratio, activity ratio, and P/E ratio. Correct manipulation of agency costs can lead to a tremendous positive impact in all aspects of these financial parameters – the main aim of my research is to document this impact – through case studies as well as statistical analysis.

One of the important highlights of researching agency costs is understanding the unique environment of Germany. It’s a country where labor unions are stronger than anywhere else, banks have the power to appoint a board of directors, institutional laws are set up to prevent a hostile takeover of German firms by foreign firms. Among this unique scheme of things, the aim has been to find a positive impact of agency costs using case studies (Daimler-Chrysler and Mannesmann-Vodafone). This has simultaneously opened up understanding on the issue called agency conflicts. Various agencies face their own unique conflict scenarios (which have been defined in section 2.6) – how they actually manage to emerge from there is the central focus of my research.

The evidence from my research supports the hypotheses/theories discussed early on.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor ______ for all his support and guidance and suggestions throughout this research project.

I also would like to thank _____ for generating interest in mergers and acquisitions through his impressive M&A lectures.

A special thanks to Professor _____ and Professor ______ for providing the initial knowledge in the corporate finance field.

I also would like to thank my family and friends who have been always supportive.

List of figures

- Fig.1: Comparison between Executive compensation (agency conflict) and Profitability ratio for 200 sample firms

- Fig.2: Comparison between Executive compensation (agency conflict) and Liquidity ratio for 200 sample firms

- Fig.3: Comparison between Executive compensation (agency conflict) and Debt ratio for 200 sample firms

- Fig.4: Comparison between Executive compensation (agency conflict) and P/E ratio for 200 sample firms

List of Tables

- Table 1: Top 10 German Corporations in terms of M&A activities

- Table 2: Ownership of Listed Corporations in Percent, the 1990s

- Table 3: Corporate Performance, Selected Averages 2000

- Table 4: Mergers by Type of Diversification in Germany

- Table 5: Largest shareholders (ownership) of Mannesmann AG

- Table 6: Regression statistics for comparison between executive compensation (agency conflict) vs. profitability ratio for 200 German firms

- Table 7: Regression statistics for comparison between executive compensation (agency conflict) vs. liquidity ratio for 200 German firms

- Table 8: Regression statistics for comparison between executive compensation (agency conflict) vs. debt ratio for 200 German firms

- Table 9: Regression statistics for comparison between executive compensation (agency conflict) vs. P/E ratio for 200 German firms

Introduction

Overview of Research

Global mergers and acquisition activity (M&A) stood at $4 trillion in 2006 (Fin Facts Ireland, 2007) and is expected to scale $5.1 trillion by the end of 2008 (Fin Facts Ireland, 2007). Germany is today the fourth largest source for M&A after the US, Japan, and the UK with a gross valuation exceeding $300 billion in 2007 (Financial Times team, 2007). According to the German Central Bank, M&A activities are today, acknowledged as the main driving force behind the country’s enduring attempts at controlling recession, rising interest rates, and other economic problems such as unemployment issues (Bundesbank, 2007).

The importance of these activities can be gauged from the fact that almost 1 out of 2 public listed corporations (at DAX, Germany’s premier Stock Exchange) have some kind of M&A activity to keep it in business in the current economic scenario (Bundesbank, 2007).

A salient feature of German M&A activities is the preponderance of its Central Bank (and as of now, the European Central Bank) in conducting and facilitating such movements (Bundesbank, 2007). It is remarkable to note that even though there aren’t any major structural differences between German corporations and their Anglo-Saxon counterparts the USA and the UK, banks in Germany historically had a more active say in deciding the fate of such major issues (Bundesbank, 2007), a bureaucratic hurdle which often proved costly because it inevitably led to failed mergers, especially when it came to international M&A.

However, old traditions are now fast-changing; Germany, like other competitive global economies, is totally upbeat about endorsing radical M&A deals which depend on a new textural framework – the underlying medium of Banks is now replaced by what are called agencies – an assortment team of executives, management and stakeholders (including shareholders) (Bundesbank, 2007).

This dissertation aims to understand and evaluate the precise role of German agency conflicts in steering the course of corporations towards an eventual successful merger. The output of these mergers is measured in terms of indices like profitability (and other financial ratios in Chapters 3-4), a number of bidders, forms of payment, the relatedness of the businesses, and additional model specifications to calculate variations from desired functionality of such M&A activities (Feils and Josephine, 1993). In this dissertation, I’ve attempted to achieve approximate values of these indices through a detailed study analysis of 200 German corporations in lieu of the presence/absence of such agencies in consolidating the deals.

Table 1: Top 10 German Corporations in terms of M&A activities (2008) Source: Rothschilds, 2008.

The above table gives a schematic look into the present worth of top German corporations which have been affected by M&A deals in the last two years.

Rationale for Study

As a Masters’s student in Finance, research into M&A activities is of enormous academic interest to me because of its vast potential and application in today’s economic scenario. In keeping with my career aims as a financial analyst with leading global investment banks, this dissertation offers an unprecedented approach in analyzing crucial situations which pass through conflicting stages before a perceived M&A activity translates into real action. Future prospects of study can be extrapolated from findings and discussions centered on major financial movements in the world.

The choice of Germany as the focus of my research is based on various factors of economic/academic interest:

- Germany is the largest and most stable European economy and considered a respected heavyweight in EU decision matters along with France, a fact which renders it the ability to project importance on a global scale as no other European country can.

- Modern-day M&A activity from a financial analyst point-of-view, is studied as a reflection of the sheer diversity of corporations in a given economy: Germany is home to a plethora of global multinationals in all diversified sectors: banking and finance, pharmaceuticals, automobiles, the high tech industry and software, news media, telecom, retail sector, advanced fields such as biotechnology and space research. In almost all sectors of its economy, Germany has made itself a definite impact across the global stage. This unique situation allows financial analysts to decipher subtle nuances of economic parameters associated with any M&A activity.

- German corporations have some of the most nuanced formulas in operationalizing pending M&A deals which offers a unique glimpse into the corporate environment and business culture of that country, a trait observed in various modules of deal finalization that will be recorded in this dissertation.

In order to translate M&A activities taking place under the above criteria, one has to peruse various theories of accounting as a direct function of investment situation for any entity undergoing transformation. M&A study offers a lot of scopes for financial analysts to sharpen their accounting skills because of the sheer complexity of mechanisms that deal with their finalization. By conducting my own independent research in this field, I seek to develop my profile for internship in renowned agencies/brokerage firms – to form a close picture of my research capability in analyzing strengths and weaknesses of firms undergoing different forms of M&A deals.

Outline

In order to properly illustrate different aspects of M&A study, I have taken a holistic approach to how these deals influence various levels of corporate decision-making in Germany; a society that thrives on a famous propensity for industriousness and efficiency. M&A deals undergo strictures of bureaucratic rules and elimination criteria before they can be implemented and merger agencies play a very important role in facilitating these mergers. The dissertation has been divided into the following chapters:

- Chapter 1, Introduction, consists of a basic overview of the German M&A industry and the main research aim concerned with M&A deals in the country. In order to properly evaluate the aims of the present research, various indices like profitability have been mentioned.

- Chapter 2, Literature Review, offers a theoretical framework of M&A activities, as applied to understanding the precise role of agencies (executives, shareholders, management) in conducting M&A activities in Germany. The information presented in this review is developed from a database of books, journals, and public databases derived from peer-reviewed sources. The facts mentioned in the Literature Review aid in the consolidation and validity of findings which will be discussed in our case study for German firms which had successful M&A activity in the last three years.

- Chapter 3, Data and Methodology deal with standard equations, evaluation methods, etc. (in our case, regression analysis) – attributes that help in understanding desired functionalities for successful M&A firms. Examples from validated research studies (peer-reviewed journal sources) have been tabulated and summarized with the aim of guiding further study objectives.

- Chapter 4, Analysis and Discussions presents a statistical overview of parameters illustrated in the previous chapter. The software Minitab version 6.0 has been used to achieve various correlation values for M&A parameters like profitability index and other financial ratios. Since statistics comprises the core part of this review, it has been done with the aim of verifying secondary information presented in the literature review.

- Chapter 5, Conclusion and Study Recommendations highlights the main achievements of this dissertation and offers conclusive guidelines for my future academic/work interest in the field of corporate finance – the role of this M&A dissertation study in preparing my career interests has been framed.

Literature Review

Overview

The aim of this chapter is to present a comprehensive theoretical framework on which global corporations achieve successful M&A deals and the unique role of agencies in facilitating and consolidating such deals. This chapter will seek to theoretically establish that with the passage of proper agency controls such as perks and incentives, any enterprise maximizes its business value amid the fast-changing scenario of international mergers. Also, a varied discussion of unique Germany’s business climate and its application in consolidating M&A deals has been made to support the research aims of this dissertation.

Understanding Mergers and Acquisitions in an international business scenario

According to Hitt, Harrison, and Ireland (2001), understanding international M&A deals comprises of understanding effective actions and processes, as well as common pitfalls/hurdles which give a more realistic evaluation sheet of how a merger will go ahead (p.4). According to a McKinsey study, only 23% of global M&A deals actually culminate into eventual business entities (Hitt et al, 2001, p.5). This envisages the agency teams behind the mergers to look more closely into obstacles that will lead to problems in the long run. Some of the common pitfalls/hurdles identified are:

- Managerial differences: When executives (especially board directors) differ on the general direction in which the corporation is going ahead and the eventual propensity of enterprise to integrate the acquired firm into acquiring firm. Personal differences between management teams may exacerbate the situation in which the corporate entities finalize an agreement (Hitt et al, 2001, p.7).

- Cultural differences between merging firms: Two large corporations have diverse business environments which often preclude any smooth sailing in an agglomerate formed by their merger. This diversity is based on cultures, structures, operating systems, competitiveness criteria and thus, can prove to be the biggest stumbling block towards an eventual merger (Hitt et al, 2001, p.7). Any mismatch in business cultures can prove to be fatal as far as the corporation’s reputation is concerned – a bad merger is like a failed marriage and conflicts in business environments has been found to be the singlemost factor in corporations declining potential M&A activity. The role of facilitating agencies, in such uncertain scenarios, becomes even more pronounced and worth appreciation.

- According to Walter (2004), the biggest problem in successful M&A activities comes from firms having systems integration using Information Technology (IT). Most modern organisations have to provide consistent customer experience for their products/services in fields as varied as analysing market demand, data distribution, product quality coordination etc. (Walter, 2004, p.129).

Today, most major corporations have a thriving demand for upgrading their IT infrastructure in keeping with customer-centric business approach. This infrastructure extends to several domains including ERP, sales, marketing, inventory analysis, advertising and other such endeavours. It is evident that any successful merger between (two large organizations) leads to a complete upheaval of existing IT systems which have to be now coordinated in a combined corporate entity. Combining information systems from two disparate cultures leads to a mind-boggling array of data which has to be processed correctly in order to avoid inconsistencies in the long run (Walter, 2004, p.130). IT savings are at the central focus of agencies seeking to achieve successful final mergers in a competitive business environment.

Agency theory in M&A

The biggest responsibility of agencies supervising intended mergers is their ability/capacity to create value from the intended merger (Sudarsanam, 2004). According to Chandler (1990), financial management (internal) of big corporate entities is only possible in “stable environments” which are relatively debt-free. However, in case of M&A activities – such corporations always look up to external creditors to fund the mergers and thus, Chandler’s theory predicts that conglomerates investing in mergers need to do the bidding of major shareholders/creditors that invest in such ventures.

A conflicting opposite theory analysing the approach of corporate behaviour called “Agency Theory” that in case of M&A activities, managers should pursue their own self-interests to that of shareholders (Peck & Temple, 2002, p.364). This includes a set of processes such as value maximisation, compensation arrangements for executives (this parameter will play a major role in our data analysis for this dissertation), debt financing and takeovers, sometimes even hostile takeovers (Peck & Temple, 2002, p.364). Hostile takeovers in agency theory refers to spending “excessive amounts” of money on an M&A investment which is a non-value maximising behaviour (Jensen, 1986).

According to Ravenscraft and Scherrer (1987), the biggest step that must be taken before finalising a merger is identifying situations which will “benefit” the agency against those situations which will create problems in the long run. Market efficiency rules dictate the general direction in which a merger is conducted by the agency and eventually, consummated by market forces as a general win-win situation for all parties concerned (‘acquiring” as well as “acquired”) Ravenscraft and Scherrer (1987). Like other authors’ definition, Ravenscraft and Scherrer (1987) identify a good merger as a successful marriage where agencies role is always prominent.

Apart from financials, Agency theory also encompasses “social” dimensions. Let us take a closer look into the psychological side of M&A activities from the focus of key decision-makers in the mergers: the management. According to Frensch (2007), agency theory envisages that the interests of principals (owners) and agents (executives/management) cannot be taken for granted i.e. assumed to be a smooth sail (p.30).

No matter how much consensus one generates, there is bound to be “conflict” between different sides on subtle issues of the proposed merger. Thus, any management motives for the conduct of mergers is unilaterally based on some measure of agency conflict – according to different experts, the best an agency could do is start with the assumption that there will be some conflict as the merger goes ahead (Eisenhardt, 1989; Buhner, 1990).

The best way to override such conflicts in key merger situations is to suggest incentives that alleviate financial concerns of one and all. Jensen (1986), in this regard has proposed a “free cash flow theory” which is going to be the underlying principle for our data analysis in this dissertation. This theory suggests that in the event of successful M&A activities, managers have incentives to grow their firms beyond the optimal size (Jensen, 1986, p.323). Thus, managers should prefer to leave free cash flow in control of their own teams instead of relegating the responsibility to shareholders (owners) of the firm. This enables them to achieve realistic and pragmatic solutions to any agency conflict that may arise due to differences in financial settlements.

A related hypothesis is based on the principle of size maximisation for the merging firm. According to Malatesta (1983), the aim of firm management should be to increase its power and prestige with the help of corporate growth (i.e. maximum value to the “firm”) regardless of the value it generates for shareholders (owners) in the merged entity. Whenever executives get a free rein over the way firms have to be steered in the most suitable direction for ensuring steady cooperation with all parties in the M&A activity, agency theory dictates it would automatically translate into maximum value for the enterprise (Malatesta, 1983).

Coleman (1990) mentions in his Rational Choice theory that individuals (in our case, agency heads) will invest in only those relationships where the expected gain – given by probability of the gain multiplied by the height of the gain will be higher than the expected loss in a relationship. These parameters are calculated based on “past experience” and “individual aspiration” level for various executives in question. Agency theory offers plenty of scope/opportunity for merging firms to evolve within a proper framework of successful management principles and culminate in meaningful deals in due passage of time.

Correlation between Executive Payout and successful M&A activities

According to Tosi & Gomez-Mejia (1989), there is a strong correlation between executive payout of a firm (measured in terms of ownership distribution in that firm) and the eventuality of a successful merger. A survey conducted on 175 US manufacturing firms revealed that there was a direct relationship between shareholder (ownership) interference in payout packages and the ability of firms to successfully complete big mergers (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1989).

This principle is corroborated by other sources of literature for Canadian and Australian M&A activities (Bakir, 2005; Macdonald, 2001; Palmer & Barber, 2001). “Contracts” between the agency and ownership define the degree to which incentives should be awarded to managers in the best interests of the merging firm (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1989). Also, most managers prefer “less monitoring” and “lower risks in the reward system” as a way to disentangle payout from performance (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1989). It eventually leads to reduced potential agency costs (Demski, Patell & Wolfson, 1984).

The level of monitoring and control in such enterprises is decided on the basis of different possibilities (hypotheses). For the purpose of our dissertation, the following hypotheses have been identified which detail the contribution of executive compensation in ensuring smooth M&A activities:

Hypothesis 1

The level of monitoring and incentive alignment will be greater in owner-controlled firms than in management-controlled firms (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1989). This basically suggests that agency costs are automatically minimised when CEO compensation is related to firm performance or other determiners regarding actions taken by executives (Mirrlees, 1976; Holmstrom, 1979; Lazear and Rosen, 1981; Grossman and Hart, 1983; Lambert, 1983; Murphy, 1986).

Hypothesis 2a

There will be lower “compensation risk” in CEO pay policies in management-controlled firms than in owner-controlled firms (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1989). As a corollary Hypothesis 2b, too much monitoring and incentive alignment will increase the level of risk for both owner-controlled firms as well as management-controlled firms (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1989). This hypothesis validates our earlier assumption separation of “ownership” and “control” is a mandatory requirement for any agency proceeding with bold M&A activities (Shavell, 1979).

This is based on research that a downside hedge in the pay of CEO’s in mnanagement-controlled firms is more closely related to size and not performance (Dyl, 1998). Accordingly, it can be suggested (by combination of hypotheses 2a and 2b) that it in the absence of monitoring, owner-controlled firms will do good by transferring most risk to agencies and management, a condition which should be reflected in executive compensation strategies (Antle and Smith, 1986).

Hypothesis 3

The third set of hypothesis deals with the influence of various stakeholders in setting executive compensation in given scenario. It suggests that the structure of CEO pay (associated stocks, perks etc.) relates directly to the degree and type of control reflected in an organisation (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1989, McEachern, 1975; Allen, 1981; Kroll, Simmons and Wright, 1975). In management-controlled firms, board appointments are made by the management (Herman, 1981) and sometimes, consultants are hired to create a level-playing field for “rational pay determination process” for concerned management team (Pfeffer, 1980).

Although, such measures have warranted a lot of criticism from auditing agencies which confer that there are fewer “checks and balances” in the system and decision-making process (Williams, 1985). However, in all fairness, such measures have won the approval and support of large management/auditing teams in Anglo-Saxon countries and as modern M&A trends emerge in Germany, these legitimising processes can gain as much popularity in Germany.

Since, the objective of our assessment report was to document the most common principles (hypotheses) serving as determiners of executive compensation for merging (M&A) entities, an elaborate understanding of details will only serve to accentuate our knowledge of processes/systems/methodologies which ensure a successful correlation between executive payout and end results. The following research strategy is recommended for such goals:

Compensation Risk Score

It gives compensation risk scores for bonus, long-term incomes and other perks against greater managerial risk bearing (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1989).

Influence Measures

Various actors in an M&A entity, the CEO, major stockholders, compensation committee, outside consultants and the CCO are identified as influencing variables with a risk score varying between “low” and “high” from the start of the deal to its successful culmination (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1989).

Control variables

Three control variables identified for the purpose of compensation evaluation can be job tenure, outside hire and firm size (Tosi & Gomez-Mejia, 1989; Roberts, 1959; Agarwal, 1981; Hinkin, 1987). CEO’s hired from outside were given a value 1 and those promoted from within a value 0.

M&A’s in German-specific business scenario

Of recent, corporate governance in Germany has become the norm in all matters of business development, a model copied from Anglo-Saxon countries which basically envisages institutionalisation of shareholdings (Drobetz, 2003). As discussed in previous section, most “ownership” firms run on the belief that stringent laws and regulations can prevent management self-interest and thus, allow for smooth M&A activities (Drobetz, 2003). This assumption has been held incorrect by the set of hypotheses (I, II and III) discussed in previous section.

Germany as a macroeconomic entity, is of special interest to financial analysts in many aspects of capital market issues. The German Corporate Governance code for legal mergers is defined as follows:

“The purpose of corporate governance is to achieve a responsible, value-oriented management and control of companies. Corporate governance rules promote and reinforce the confidence of current and future shareholders. Lenders etc.” (Drobetz, 2003)

In terms of integrated financial markets in Germany, the traditional Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) predicts that expected returns on equity only depend on the level of risk with world markets scenario and corporate governance has no role. It has been discussed previously that banks (and other public institutions) play a leading role in governing corporate affairs in Germany, an aspect of M&A which is very different from Anglo-Saxon mode of business activities (Drobetz, 2003). The concerned model is reflected in “ownership controls” as depicted in following table, Table 2:

Table 2: Ownership of Listed Corporations in Percent, 1990s (Source: Höpner and Jackson, 2001).

As can be verified from above table, ownership in Germany is highest for non-financial firms and banks (at 13.5% and 29.3% respectively) which is far higher than either the UK or the USA. This translates into stronger centralised structures which allow for employees comprising an important force in any decision-making concerning M&A activities. M&A agencies in Germany simply cannot afford to ignore the voice of employees as they get a final say on decisions varying from long-term profit maximisation and are a serious force to reckon with in decisions concerning the organisation’s future (Höpner and Jackson, 2000).

Germany’s meteoric rise in international trade from the shambles of World War II has much to be associated with the ascendancy of labour unions in deciding terms of M&A activity in the country. These symbols of German industry are very different from the short-termism, opportunism and breach of trust that is common with Anglo-Saxon organisations (Höpner and Jackson, 2000).

In all fairness, as per our hypotheses in previous section (I, II and III), high ownership concentration as evidenced in Germany has serious repercussions in terms of lack of capital liquidity, lack of risk diversification, costs for small shareholders unable to share the private benefits of control accruing to large shareholders etc. (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). On one hand, it prevents foreign-owned firms from staging hostile takeovers of German firms leading to job loss. On the other hand, it can lead to long-term inefficiency and bureaucratic bottlenecks which are difficult to overcome for sensitive business decisions such as M&A activities.

One important question that comes to mind here: why do shareholders in Germany tolerate receiving less of the corporate value due to employee-centric financial mechanisms? This is because quite until recently, marginal returns to shareholders were favourable giving less reason to defect (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). High share prices can be sustained with high earnings or low prices can be sustained with low earnings as is demonstrated by the following equation:

Earnings/price share X dividends/earning = dividend yield where

Earnings = retained earnings + dividends = value added – depreciation – labour – taxes –Interest (Höpner and Jackson, 2000)

These patterns are described in following table, Table 3 which illustrate a comparison between German and British corporations as far as price-earnings ratio and dividend yields (refer equations above) are concerned. German companies follow a “low-level” equilibrium which indicate low earnings and dividends corresponding to lower share prices (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). Shareholders receive competitive returns in Germany because of “high turnover”, global market presence and lower payments to investors (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). In the long run, however, it has to be seen that such “equilibrium” models don’t work out in present-day recession scenario. Germany, like many other countries, is opening up to business cultures that have taken root in Anglo-Saxon countries.

Table 3: Corporate Performance, Selected Averages 2000 (Source: Höpner and Jackson, 2001).

As can be observed from above table, German corporations have traditionally relied on sales, profits and employment figures for sustaining their own in competitive markets as against market valuation and dividend yield goals more prevalent in Anglo-Saxon countries. The diminished importance of shareholders in firm decision-making prevents hostile takeovers. Thus, Germany has a guidance yardstick of M&A activities which strongly depend on corporate governance rules This fact has to be kept in mind when understanding associations of German companies with concerned M&A activities taking place in its own unique business culture. German business culture is also applicable to Switzerland and Austria.

Let us now understand the structural diversification of German M&A activities. Horizontal diversification refers to M&A activities within the same product line (range) for two or more companies. Vertical diversification refers to M&A activities within the stratified layers of supply chain delivery for the same corporation e.g. when Daimler-Chrysler merges its auto division with ancillary parts. As seen in table below, most mergers in Germany take place across a horizontal stratum. This indicates a high degree of openness as far as proceeding with mergers in the business interests of the companies are concerned. Germany is no less open to M&A activities compared to Anglo-Saxon business cultures.

Table 4: Mergers by Type of Diversification in Germany (Source: Höpner and Jackson, 2001).

Agency conflicts in German M&A activities

Agencies in Germany have to undertaking big corporate mergers have to address key conflict issues related to various institutional factors which are unique to the country’s business/economic environment. These conflicts highlight the challenges and opportunities present in various operationalisation stages of M&A activities which bolster the case for executive (management) insight.

- Ownership structure: Private companies in Germany exist as GmBH and there are no major open markets for shares in unrelated business scenarios (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). Out of every 100 German firms, 57 are majority-owned which is further divided into families, government and banks. This is in sharp contrast to Anglo-Saxon corporate entities which tend to be openly listed on the stock exchange.

- Influence of Banks: As has been discussed before, banks in Germany have a crucial role to play as far as successful mergers are concerned (Höpner and Jackson, 2000).

- Codetermination: Unlike Anglo-Saxon corporate entities, employees in Germany have their voice heard during any M&A activity discussions. Hostile takeovers of German firms by foreign owners is made difficult by the “veto” power enjoyed by employees, and employee organisations (Höpner and Jackson, 2000).

- Accounting and disclosure issues: German accounting and disclosure figures have a bad reputation for lacking transparency in records (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). Traditionally, German accounting has stressed on traditional accounting methods which vary from GAAP norms followed in Anglo-Saxon countries which consequently, are more investor-oriented (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). Bidders in Germany are able to achieve large stakes without being credit-detected.

- Company Law: Corporate law in Germany prevents hostile takeovers by separating voting rights from the factual ability to control (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). Under a two-tiered board structure, shareholder representatives in supervisory boards for German entities can only be removed when their actual term expires (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). In some cases involving hostile takeovers, minority have denied blockholders representation on the supervisory board using their veto power (Höpner and Jackson, 2000).

- Competition Law: Germany has a unique competition law upheld by the Federal Cartel Office which is basically an anti-trust law preventing foreign competition from gaining vital access points in such merging entities (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). This obtrusive law has come in the way of successful mergers in the past, e.g. the failed Daimler-Chrysler merger in 1998 where Chrysler was a US corporation which was unable to satisfy “internal criteria” relevant to Germany’s competition law (Höpner and Jackson, 2000).

- Defensive Actions: Managerial defences against takeovers are common in US corporate environment; Anglo-American managers are allowed to buy back shares, have multiple voting rights and apply intervention before a merger proceeds (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). German law does not give management similar powers to trouble-shoot the problem once an M&A activity is underway (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). Germany has a unique mechanism which requires “registration of management shares”, a concept unheard of in Anglo-Saxon business parlance (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). Management in Germany can refuse to “register” the shares of an acquiring firm thereby, delaying or denying their right to exercise shareholder rights.

- Corporate Culture: German corporate culture is based on a strong emphasis for “structural” and “organisational” aspects of management which is very different from the “financial-centric conceptualisation” common in Anglo-Saxon countries (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). There is a strong orientation towards consensus decision-making within the board itself. Germany has a relatively weak “equity culture” common in other countries which forestalls the possibility of agencies to write off biddings based on their own judgement and that of shareholders (owners) (Höpner and Jackson, 2000). M&A decisions are genuinely consensus-centric.

Some case studies highlighting agency roles and conflicts in Germany

In this study, we shall take the example of two M&A activities in recent times: the takeover of an overseas corporation (Chrysler, US) by a German one (Daimler Auto) and the acquisition of a German company (Mannesmann) by an overseas firm (Vodafone PLC).

Daimler-Chrysler

Stuttgart-based Daimler Motor Company acquired US automaker Chrysler Holding LLC in 1998 to forge one of the most powerful auto mergers in recent history (Business Week, 2003). Daimler had established itself as one of the pioneering automobile companies with several popular brands under its flagship: Maybach, Mercedes-Benz, Smart and Mercedes-AMG. The deal was worth over $36 billion and was completed over a period of time 3 years (Business Week, 2003).

The deal had met criticism from US media because of class-action lawsuits focused on technical illegalities of the arrangement which precluded any opinion of Chrysler shareholders; the deal itself was seen as a hostile attempt by the then-Daimler CEO Dieter Zetsche as a mismanaged business entity devoid of common principles/framework. By 2003, Chrysler ended with a loss peaking $2 billion and eventually Daimler was forced to re-sell the company to Cerebrus Capital Management in 2007 for $6 billion (Car and Driver, 2007). Clearly, business analysts see this failed merger as a disaster that was waiting to happen: it wasn’t all hunky-dory right from the very beginning of this event.

The reasons for Daimler’s miscalculation in associating itself with a company which was already in the red in terms of shareholder value can be attributed to the immaturity of German management in understanding American “fiscal” culture. There was already a relentless downward pressure in the US market as far as cash flow is concerned (Business Week, 2007).

Even before the deal was finalised, Daimler saw itself pumping a lot of money into a failed corporate entity because the merging agency (German-based) relied on failed criteria which failed to interpret Chrysler’s contemporary fiscal standing: it was a bottomless pit from the very beginning. The reasons why Daimler failed to read the signs can be attributed to the inexperience of merging agencies in assessing conflict situations that wasn’t part of German corporate dictionary (see section 2.5).

For the start, Daimler as all other German corporations back then did not have enough idea about trans-Atlantic accounting and fiscal standards. As has been mentioned previously, German corporations due to their unique culture rely more on “gut instinct” than “fiscal/financial/accounting” variables as far as finalising an M&A activity is concerned (Business Week, 2007). The merging agency chose to ignore recommendations made by concerned strategists that American corporations operate in a very different environment where share-price value can affect the health of a company much more rapidly than in Germany.

The two key people associated with this merger, Jurgen Schrempp (CEO) and Dieter Zetsche (“minority” member at Daimler Board of Management) were also “codeterminers” in terms of their background which was purely industry-based and lacking expertise in finance and equity (Business Week, 2007). Also, their interests were closely aligned to worker unions in Germany than ownership (shareholders).

The second hypothesis in executive payouts played a role in these unsuccessful mergers – according to section 2.4 Hypothesis 2a– a lower “compensation risk” in CEO pay policies in management-controlled firms than in owner-controlled firms led to inadequate attention paid by German board of directors on the “specific American situation” of the acquired firm and its unique business environment. Also, as a corollary Hypothesis 2b, too much monitoring and incentive alignment led to an increase in the level of risk for both owner-controlled firms as well as management-controlled firms

Vodafone-Mannesmann

Mannesmann’s hostile takeover by Vodafone PLC in 2000 was then seen as the biggest acquisition by an overseas firm on German soil (Höpner and Jackson, 2001). It used to operate Germany’s second-largest telecom company after Deutsche Telecom and by the 1990’s was a successful entity in its sphere of operations. Klaus Esser was appointed as the chief financial officer of the board (identical to CFO in Anglo-Saxon countries) and was acting as chair (CEO) by 1998 (Höpner and Jackson, 2001). As is common with German corporate culture, Esser was an engineer and not a financial analyst – in an environment where engineers are more valued for business decisions compared to financial experts.

According to the third hypothesis of executive payouts, the structure of CEO pay (associated stocks, perks etc.) related directly to the degree and type of control reflected in Mannesmann (section 2.4); events of the day made it obvious that Esser was having a difficult ride in trying to enhance the overseas image of Mannesmann a competitive firm – in order to salvage the loss-making situation, it was forced to undergo a competitive merger with its rival Vodafone in a private deal.

Even though the eventual deal was successful, the role of agency conflicts in shaping different facets of the takeover offer an excellent glimpse into the unique situation faced by overseas corporations when operating in a German business environment. The problems presented in Mannessmann’s acquisition by Vodafone offers a perspective into agency conflicts that exposed the inherent, intrinsic weaknesses of German corporations in their isolated business cultures. Let us take a closer look into different agency conflicts in the German corporation.

Ownership

Mannesmann’s ownership structure was unique from a German point-of-view. Most part of the company was foreign-owned (over 60%) well before the merger took place.

Table 5: Largest shareholders (ownership) of Mannesmann AG (Source: Höpner and Jackson, 2001).

Defensive Actions

Mannesmann’s defensive strategy was very different from traditional German companies (partly due to its foreign ownership but that is nullified by the fact that German corporations retain all veto rights as far as key business decisions are concerned. Partly due to its strong belief in German laws, Klaus Esser never considered any hostile takeover bid by Vodafone as a serious challenge to its business decisions (Höpner and Jackson, 2001).

The takeover bid was pursued when Mannesmann attempted along with Vodafone -to acquire UK-based Orange corporation in June, 1998 for around $30 billion – this eventually led to Vodafone controlling nearly 35% of Mannesmann’s shares (Höpner and Jackson, 2001). Since, this size of control was beginning to threat Mannesmann’s home market (unlike other German corporations, Mannesmann had no power under German law to “de-register” Vodafone’s acquired shares because they were based in overseas territory).

Later, when the deal started taking shape in terms of control contracts, Vodafone started claiming control in terms of simple majority which was challenged by German legal who suggested that Vodafone “did not go according to a routine managerial decision as mandated by German law” (Höpner and Jackson, 2001).

The Role of Banks

Even though banks play a major role in M&A activities taking place on German soil, it was not the case for Mannesmann – German banks showed little or no interest in Vodafone’s hostile takeover (Höpner and Jackson, 2001). In the late 90’s, German banks started attempting a major transformation into investment banking – a change from traditional relationship banking. In fact, according to Klaus Breuer, the chairman of Deutsche Bank –he saw this merger as a first “large case” within Germany’s financial culture (Höpner and Jackson, 2001).

The role of codeterminers (labour unions, work councils, employee share ownership and other unions)

This was the biggest agency conflict which came in the way of Vodafone attempting to pursue a full-scale merger of Mannesmann. Up until February 2000, individual employees had a 7.5% stake in the company and there were fears for job losses (Höpner and Jackson, 2001). Mannesmann had some of the strongest codeterminer laws among German corporations and Vodafone had to face off consequent negative publicity in German media and stiff resistance from conglomerate-level work councils (Konzernbetriebsrat).

Most legal codetermination rights were well in place in Germany as the conflicts arose between capital market-oriented management (Vodafone) and codetermination (Mannesmann). Vodafone had a lot of homework to do as far as placating the concerns of codeterminers –mostly reassuring employee stakeholders regarding job losses which were to be avoided by all possible means.

Vodafone’s legitimate attempt at taking over Mannesmann has heralded a new array of solutions for overseas corporations looking for M&A activity within German business environment. The outstanding merger highlights the changes and needs required of Germany if it has to thrive in an increasingly-competitive global market.

Data and Methodology

Data collection

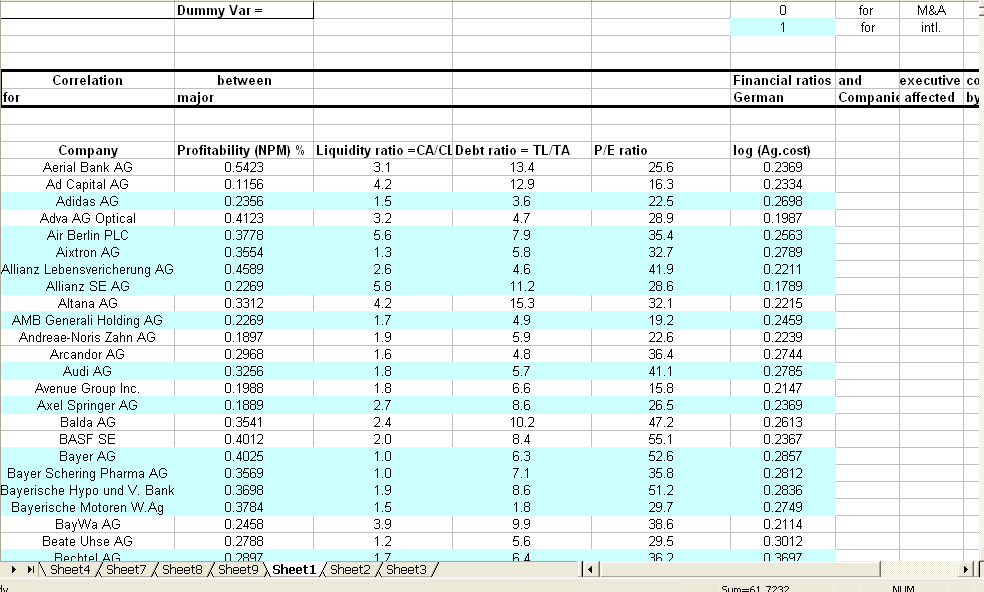

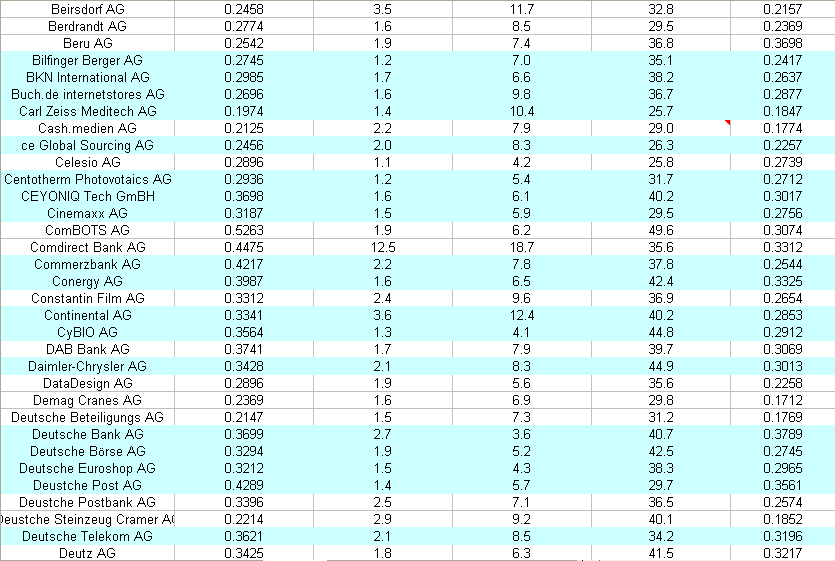

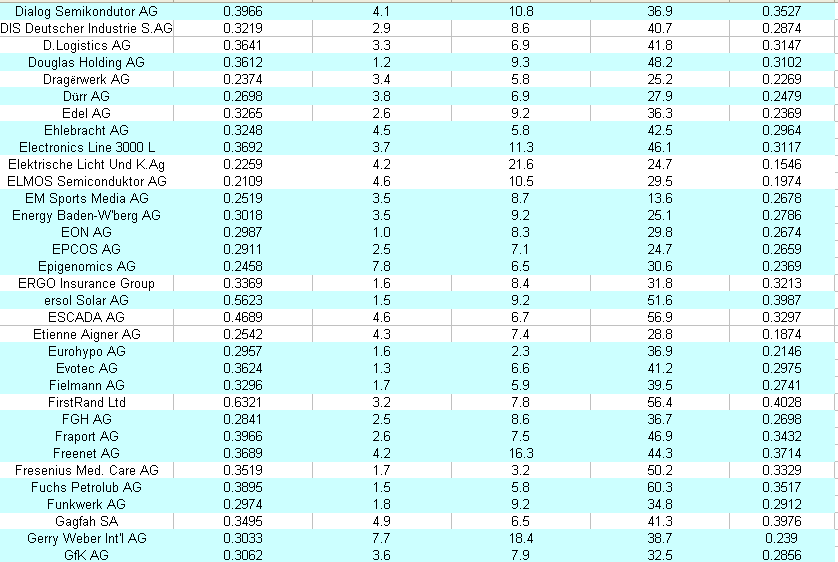

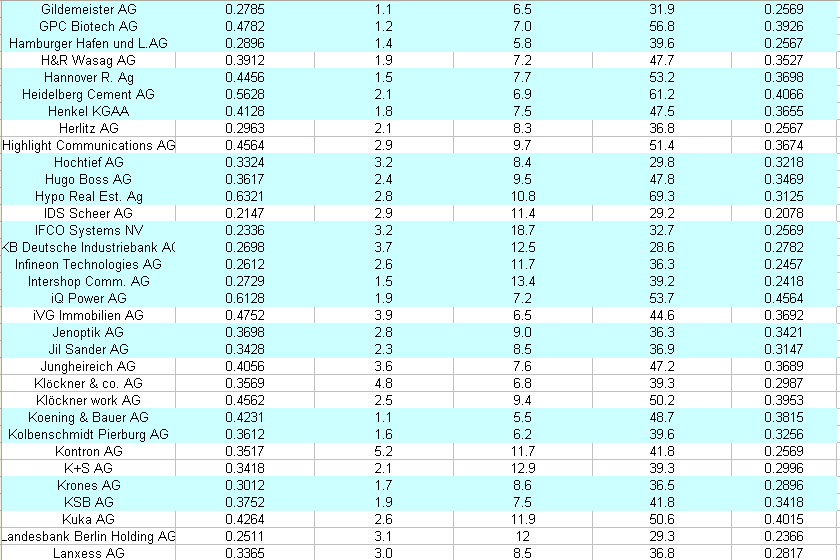

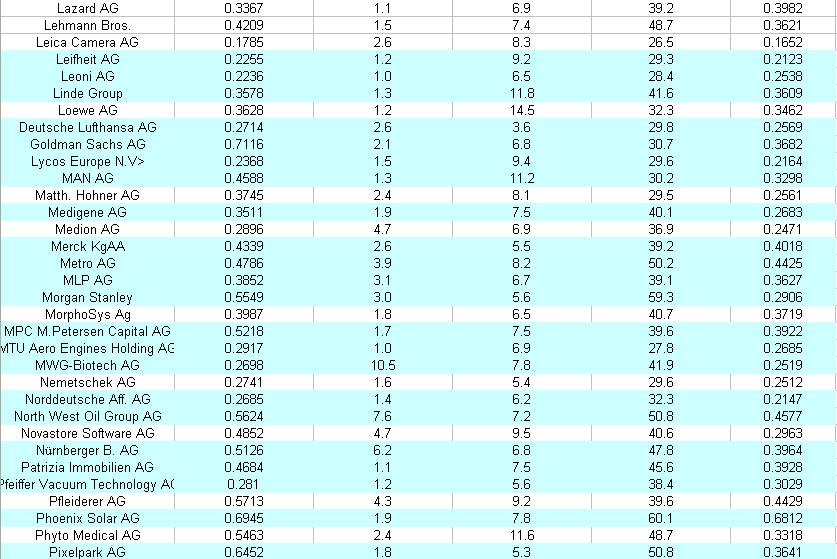

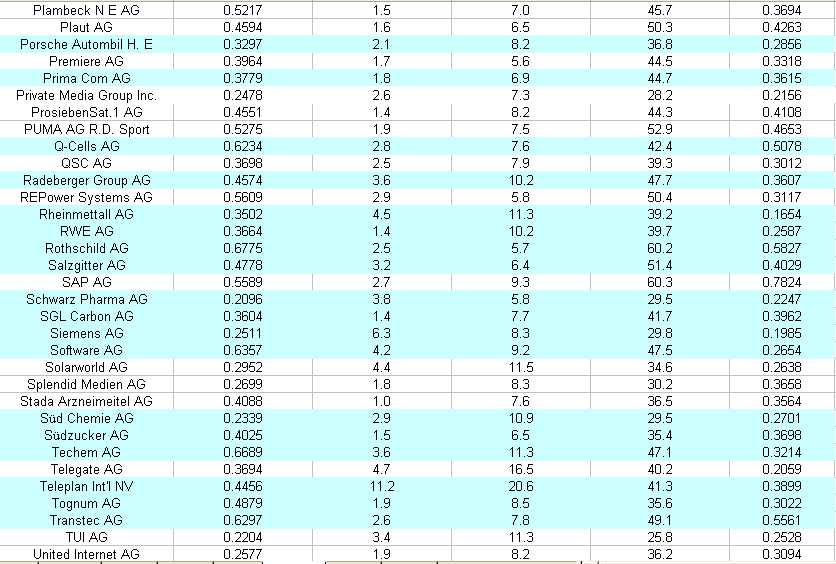

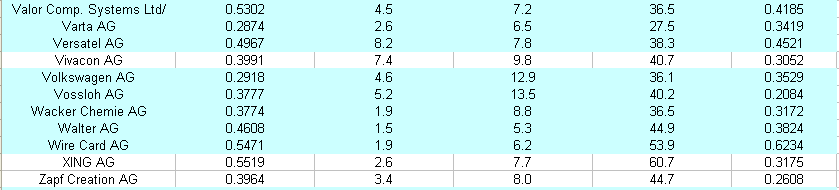

The data required for our analysis of agency conflicts in German M&A activities has been collected from Hoover Corporation which is a worldwide resource for company data in terms of market figures sales, profits, revenues etc. and also, financial ratios which will be discussed in this chapter. Around 200 German firms (see Appendix I) have been selected on the basis of their listing in German stock exchange (DAX). Also, all these organisations had some or other stake in M&A activities: horizontal integration (in case of international mergers) and vertical integration (domestic mergers). Refer Table 2.4 to understand the relevance of horizontal/vertical M&A entities in our present dissertation study.

Financial ratios

In this dissertation, we have repeatedly highlighted management compensation as the most significant-sized variable to affect agency conflicts. All financial ratios in our study have been compared to logarithm of management compensation in millions of Euros for 200 German public-listed companies between the time period 2004-2007 (gathered from company annual statements at Hoove.com). A dummy variable 0 has been used for mergers that took place within Germany and 1 for mergers outside Germany. See Appendix I for more details. All ratios used in our comparison are post-merger ratios which were based on different M&A criteria for given corporations.

Each and every agency in merging entities has its own goals and objectives as far as the general direction of the organisation is concerned. In order to conduct an empirical research on important agency parameters discussed in this dissertation, we must understand methodologies to be followed (in Chapter 4) and its impact on most strategic variables in a business scenario: financial ratios. Financial ratios for our statistical purpose has been gathered from Hoover’s entities and their annual balance sheets. These ratios have been collected from company balance sheets, income statements, cash flow statements and other accounting variables. The list of ratios used in our dissertation are:

- Profitability ratio: It measures the firms use of its assets and control of expenses to generate an acceptable rate of return. There are several ways to express this figure – in our dissertation, we use the parameter Net Profit Margin (NPM) which is basically net profit after sales/tax for the given corporation (Groppelli, 2007). The parameter NPM has been compared to logarithm of management compensation in millions of Euros for 200 German public-listed companies between the time period 2004-2007..

- Liquidity ratio: Liquidity ratio refers to the capability of a company to pay ready cash for finalised transactions. In our dissertation, we use the parameter Current Ratio which is the ratio of Current Assets over Current Liabilities (Groppelli, 2007). The parameter Liquidity Ratio has been compared to logarithm of management compensation in millions of Euros for 200 German public-listed companies between the time period 2004-2007.

- Debt ratio: Debt ratio refers to a company’s long-term capability to repay outstanding debt. In our dissertation, we use the parameter to denote a ratio of total liabilities over total assets (very different from current liabilities and current assets) (Groppelli, 2007). The parameter Debt Ratio has been compared to logarithm of management compensation in millions of Euros for 200 German public-listed companies between the time period 2004-2007.

- Market Ratio: Market ratios refer to investor response to owning and issuing a company’s stock. The most famous market ratio –P/E ratio (Price/Earnings per share) has been used in this study to completely understand the market situation of German companies involved in M&A activities (Groppelli, 2007). The parameter P/E Ratio has been compared to logarithm of management compensation in millions of Euros for 200 German public-listed companies between the time period 2004-2007.

- Activity ratio: It refers to how quickly a firm is able to convert non-cash assets to cash assets (Groppelli, 2007). Due to inconsistency of information from German sources on parameters like average sales per day and annual credits, it wasn’t possible to discuss activity ratios for the purpose of statistical evaluation in this dissertation.

Regression modelling analysis

Here is a brief discussion of linear regression modelling analysis used in this dissertation to achieve post-merger financial ratio comparison across diverse German companies used in our research sample. Regression analysis as a statistical tool is used to assess the cause-effect relationship between two variables (independent and dependent respectively). At the very outset of a regression analysis, one must make a hypothesis indicating relationship between two the variables (Sykes, 2007).

Later, a set of equations are followed (in our case, we use descriptive statistical tools in Excel software) which confirm whether or not there is a relationship between the two variables in question (Sykes, 2007). For simple situations and scenarios, it is always preferred to use simple regression analysis which suggests degree of closeness/separation between the variables as indicated by a base-line plot (Sykes, 2007). If all points in the chosen sample hug the base line, it indicates a high degree of closeness (Sykes, 2007).

Real life situations, however, are far too complex to suggest “linear” relationships

Between various variables in study. It is with this purpose in mind we must account for noise term ε in our study sample chosen. The “noise” refers to various unexplained factors which affect the final output of study (Sykes, 2007). The equation of simple regression is given as below:

I = α+ βE + ε where

α= a constant amount;

β= the effect in change of ind. (X)variable which affects output I

ε= the “noise” term reflecting other factors that influence earnings.

I = Output, the dep. (Y) variable.

When regression is carried out only between two variables, it’s called “single regression”. When it’s carried out between a number of independent/dependent variables all together, it’s called “multiple regression” which is more complex (Sykes, 2007). In our dissertation study, we have pursued single regression analysis for each and every financial ratio in discussion (except Activity ratio for which data was not available) with logarithm of management compensation in millions of Euros for 200 German public-listed companies between the time period 2004-2007 (gathered from company annual statements at Hoove.com). A dummy variable 0 has been used for mergers that took place within Germany and 1 for mergers outside Germany.

Advanced regression analysis is done in terms of statistical interpretation of empirically observed data using R2 value which is known as the sum of squared estimated errors. It basically indicates the degree of variation of dependent variable from the independent one and is considered the “meat” of regression analysis (Sykes, 2007). A high value of R2 obviously indicates a high degree of correlation between both variables which can be later used for forecasting purposes in terms of how closely-related trends are.

The R2 value also gives a real picture of the “goodness of fit” associated with concerned variables (Sykes, 2007). Residual analysis of concerned information sources gives a validated picture of how things should appear in “hypothetical” scenarios where there are no “residual” noise factors to create problems in statistical analysis.

Analysis and Discussions

Recapitulation of essential concepts

Chapter 2, Literature Review has explored various agency conflicts known for becoming bottleneck problems in M&A activities taking place in Germany due to executive (management)/shareholder (owner) difference of opinions. Unlike Anglo-Saxon countries, Germany’s unique corporate governance model does not allow for any leeway in terms of firm owners asserting their rights and privileges over company managers.

This essentially follows from key hypotheses suggested in section 2.4: Hypothesis 2a which indicates lower “compensation risk” in CEO pay policies in management-controlled firms than in owner-controlled firms, a salient feature of German corporate governance. Also, Hypothesis 3 suggests direct correlation between “executive payout/compensation” and profitability of a company/financial ratios.

Above hypothesis was put into practice in terms of identifying statistical correlation between various financial ratios and logarithm of executive compensation in millions of Euros. Around 200 German firms were short-listed on the basis of their post-merger status due to various M&A activities between the time period 2004-2007. The only reason no pre-merger comparison was possible is because our study focuses on the combined array of German firms {1,2,3,…200} rather than individual case studies.

Although, we have undertaken two case studies in isolation: Vodafone-Mannesmann and Daimler-Chrysler to achieve theoretical examination of agency conflicts and their roles in M&A activities in Germany. Primary/statistical analysis as undertaken in next section are a comparison of various financial ratios (profitability, debt, liquidity and P/E) with the most significant agency conflict parameter: executive compensation. It has been repeatedly established that the scale of executive compensation acts as the most defining instrument in signifying the degree and extent of conflict in a merging agency.

It’s clear that for our study purposes agency conflicts have been essentially summarised or attributed as a function of executive compensation. Higher the executive compensation, the better results for the company in terms of profits and improved financial ratios. As shown in Appendix I, each and every financial ratio is translated into figures to illustrate the impact of agency payout on a successful merger. The higher the given financial ratio, the better health the company has over its short-term and long-term business goals.

In order to capture the relevance of any theoretical correlation between executive compensation (agency conflicts) and various business parameters (financial ratios), the method of Regression model analysis with Residual Error has been brought into fore. The objective of this statistical analysis is not to achieve exact results as evinced in literature review case studies. It’s rather a holistic attempt at picturising real-world business scenario for various agencies in question (almost 200 in our full-fledged attempt at understanding agency conflicts in German M&A activities. These statistical results will be interpreted for any signifying agency conflict as described in section 2.6

Profitability ratio vs. Executive Compensation

Comparing the values as depicted in Appendix I at a confidence interval of 95%, we are able to achieve the following line fit plot as depicted in Figure 1.

A visual observation would confirm the obvious natural good fit for the variables of profitability ratio (and by extension, net profit) and solving agency conflict using suggested increase in compensation for executives. The executive compensation is based on data feedback from concerned annual reports. Above results can be statistically verified in terms of R2 observation in Table 6 given below. A high positive value in R2 observation (0.49) indicates dynamic similarity between the compared variables – less deviation from accepted mean definition.

Table 6: Regression statistics for comparison between executive compensation (agency conflict) vs. profitability ratio for 200 German firms.

While looking at results for standard error observations (non-existent in our case), it can be said with certainty that almost all post-merged German corporations, on average (by statistical means, over 70% as depicted in Multiple R values) were able to record a tremendous boost in net profits compared to their pre-merged status. It should be remembered these mergers suggested in our analysis refer to both vertical as well as horizontal mergers for given list of firms. Indeed, German corporations have a positive correspondence in terms of increase in profitability values with solutions of agency conflict using compensation.

Above set of results will establish the absence of any agency conflicts (refer section 2.6): except for Corporate culture: German corporate culture is based on efficiency and proper organisational aspects of management. This successful trend is reflected in the high measure of profits seen for German corporations in a given business activity – in our case, M&A activities that were selected in present study.

Liquidity Ratio vs. Executive Compensation

Comparing the values as depicted in Appendix I at a confidence interval of 95%, we are able to achieve the following line fit plot as depicted in Figure 2.

A visual observation would confirm the obvious natural improper fit for the variables of liquidity ratio (and by extension, cash flow) and solving agency conflict using suggested increase in compensation for executives. The executive compensation is based on data feedback from concerned annual reports. Above results can be statistically verified in terms of R2 observation in Table 6 given below. A low positive value in R2 observation (0.02) indicates very less similarity between the compared variables – more deviation from accepted mean definition. There are natural reasons to explain this discrepancy as these figures showcase potential agency conflicts as can be verified in the table below:

Table 7: Regression statistics for comparison between executive compensation (agency conflict) vs. liquidity ratio for 200 German firms.

In order to fully understand possible reasons for discrepancy in cash flow statements, one only needs to look at residual plots in Appendix II. They suggest several examples of companies which had an overall positive (high) correlation between the two variables –also, many companies had negative correlation. It should be kept in mind that cash flow statements only reflect the current health of an organisation i.e. the capability of an organisation to maintain liquidity against liability in uncertain business scenarios. Many companies especially start-ups remain in debt for extended periods of time. This renders them ineffectual in terms of maintaining adequate cash flow w.r.t general profits.

Above set of results will establish the presence of following agency conflicts (section 2.6):

- Accounting and Disclosure issues: It has already been mentioned that some German corporations still hesitate to follow US-based GAAP recommendations in their annual reports. This translates into bottomline figures which don’t indicate good health for the organisation.

- Bank influence: Banks in Germany often hedge funds meant for investment decisions. This prevents some corporations from maintaining regular cash flow.

Debt ratio vs. Executive Compensation

Comparing the values as depicted in Appendix I at a confidence interval of 95%, we are able to achieve the following line fit plot as depicted in Figure 3.

A visual observation would confirm the obvious natural moderate fit for the variables of debt ratio (and by extension, company output) and solving agency conflict using suggested increase in compensation for executives. The executive compensation is based on data feedback from concerned annual reports. Above results can be statistically verified in terms of R2 observation in Table 6 given below. A moderate value in Multiple R (0.12) indicates close similarity between the compared variables – comparatively less deviation from accepted mean definition as against previous example. Table below illustrate the statistics at hand in order to provide schematic glimpse into future business trends.

Table 8: Regression statistics for comparison between executive compensation (agency conflict) vs. debt ratio for 200 German firms.

Above set of results indicate similar agency conflicts as illustrated in previous example of liquidity ratio. It’s obvious many German firms do not have sufficient accounting standards and banks play a major role in allotting/blocking outlays of large sums of money for concerned operations.

P/E ratio vs. Executive compensation

Comparing the values as depicted in Appendix I at a confidence interval of 95%, we are able to achieve the following line fit plot as depicted in Figure.

A visual observation would confirm the obvious natural good fit for the variables of P/E ratio (and by extension, investor popularity) and solving agency conflict using suggested increase in compensation for executives. The executive compensation is based on data feedback from concerned annual reports. Above results can be statistically verified in terms of R2 observation in Table 6 given below. A high positive value in R2 observation (0.36) indicates dynamic similarity between the compared variables – less deviation from accepted mean definition.

Table 8: Regression statistics for comparison between executive compensation (agency conflict) vs. P/E ratio for 200 German firms.

The following agency conflicts can be posisibly deduced from above statistics/pools of information.

- Corporate culture: It has been repeatedly mentioned that Germany’s thriving corporate culture based on efficiency and workmanship is given more value than an “equity-based” financial culture prevalent in Anglo-Saxon countries. This manifests into business trends which allow better market capitalisation especially when firms consider overseas mergers.

- Role of Banks: As mentioned earlier, banks in Germany play a strong, centralised role in shaping investment solutions for firms involved in M&A activities. This role gets all the more strengthened in lieu of changing business scenarios.

- Competitive law: The relative stability in German equity markets (as against the volatility in major financial markets like London and New York) indicates the impact of the country’s unique competition laws. These protectionist measures indicate the relatively high stability of equity markets and a big hurdle for foreign firms willing to take over German firms.

- Defensive actions: It has been mentioned earlier German laws do not give managers the right to pursue defence actions in case of failed mergers e.g. buying back shares, multiple voting rights etc. Germany has a unique law which requires registration of important shares for the purpose of voting rights etc. These protectionist measures indicate the relatively high stability of equity markets and a big hurdle for foreign firms willing to take over German firms.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Summary

This dissertation has taken a highly-researched study of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) taking place in the unique business environment of Germany. This mainly involved answering questions about the scope and extent of agency conflicts on German M&A transactions. Using secondary literature evidence on “Agency Theory”, it was suggested that any two merging entities face common obstacles in terms of agency conflicts which eventually lead to unsuccessful/unhappy mergers. In order to get a firm grip on merging activities (M&A) as is the trend in Germany, we uncover the following theories/strands of information which were later tested using real statistical data drawn from balance sheets of German companies.

Agency Theory

which indicates that in case of M&A activities, managers should pursue their own self-interests ahead of that of shareholders. Literature evidence was suggested to indicate that most successful merging company managers arrogate high compensation payouts which positively impact their long-term vision for the M&A activity. Chapters 3 and 4 indicate the manner in which this theory was tested against real company data.

Germany’s unique corporate environment

This dissertation has taken a closer look into the unique business environment of Germany and its relative friendliness to M&A activities. According to the “free cash flow theory” which talk of greater management rights over shareholder ones – we are introduced to Germany’s unique economic landscape in contrast to Anglo-Saxon countries such as the United States and United Kingdom. As a nation, it has an unprecedented system of checks and balances in place which rely on

- greater role of banks in forging M&A deals;

- greater rights of managers (executives) over that of shareholders in important M&A activity decisions;

- less degrees of freedom for foreign firms seeking to stage hostile takeover of German-owned corporations;

- unique legal precedents which prevent shareholders from asserting their privilege over appointed board of directors;

- an efficiency-driven blue-collar based financial board is common to most German firms – this is as against purely equity-driven financial firm more prevalent in Anglo-cultures.

Agency conflicts

Understanding the unique business situation of Germany gives us an in-depth understanding into various agency conflicts which shape M&A activities. These conflicts mainly arise due to differences in perception between shareholders (owners), executives (managers), employees (codeterminers), banks (central institutions) and other push-and-pull factors. The common agency problems highlighted in this study (as observed from literature sources and confirmed using statistical analysis are:

- Ownership structures – Organisations in Germany are more employee-driven (social) as against private equity-based structures. This leads to numerous problems in different M&A scenarios.

- Bank Influence: Banks often have an intrusive role in deciding the course of a successful merger.

- Poor accounting standards: Germany is not up-to-date with modern accounting standards practised in Anglo-Saxon countries and this affects their deal perception with overseas merging clients.

- Defensive actions, Competitive anti-trust laws and other protectionist measures to ensure German companies don’t fall into the control of foreign Giant enterprises.

Case Studies

In order to consolidate and integrate above pieces of literature, we have analysed relevant case studies of two different scenarios: a German-firm acquiring an overseas firm (Daimler-Chrysler) and a foreign firm acquiring a German flagship firm (Vodafone-Mannesmann). Both case studies (2.6.1 and 2.6.2) expose us to the unique business environment of Germany as evinced in present research. These case studies are also a first-hand account into the agency conflicts inherent in German M&A environment.

Statistical (Regression) analysis

Finally, in order to validate findings derived from literature sources, regression analysis has been used to find out relationship between executive compensation (which is defined as summary of all agency conflicts) and various financial ratios: profitability, liquidity, debt ratio and P/E ratio. Since, financial ratios indicate health of an organisation, over 200 sample post-merged German firms were shortlisted for relevant data from Hoover.com (Appendix I). The Regression analysis performed using these statistical measures indicate a close relationship between agency conflict parameters (executive compensation) and various aspects of financial modelling: profits, investor-friendliness etc.

Results

- We’re able to achieve a good fit for data concerning profitability vs. executive compensation which indicates nearly a 70% positive trend for the sample of 200 German firms chosen. No relevant agency conflict has been identified from given sample.

- We’re unable to achieve proper fit for data concerning liquidity vs. executive compensation which merely indicates a 1-2% positive trend for the sample. The high variability in information has been association to residual plots in Appendix II which indicate many firms are not in proper position to maintain positive cash flow due to individual business circumstances. This, however, exposed various agency conflicts like bank issues and accounting problems -common ailments for German corporations.

- We’re able to get a moderate fit for data concerning debt ratio vs. executive compensation which indicates nearly a 12% positive trend for the sample of 200 German firms chosen. The agency conflicts inferenced are similar to that of liquidity-operated firms viz. bank issues and accounting problems.

- We’re able to achieve a good fit for data concerning P/E ratio vs. executive compensation which indicates nearly a 40% positive trend for the sample of 200 German firms chosen. A large number of agency conflicts were identified in this regard.

Limitations of Study

The following limitations of study have been identified for this dissertation:

- The use of regression analysis is fraught with problems of multicollinearity of points along a line and missing variables. This manifested in an unavoidable large residual plot for Fig.2 and thus, results weren’t strongly suggested.

- Activity ratios could not be compared with executive compensation because of lack of data from annual reports.

- All financial data collected from Hoover.com is subjected to market change especially P/E ratio. The results are indicative and not exhaustive. A formal procedure would consist of tabulating data from surplus sources to allow impartial data analysis based on concrete information.

- There is an apparent shortage in literature concerning case studies of German corporations in various aspects of agency conflicts. This unavoidable situation was averted by closely focusing on investment reports of two case studies chosen for this dissertation (Daimler-Chrysler and Vodafone-Mannesmann). Agency conflicts were deduced based on analysis of merger situations in both events.

Recommendations for further study

As a Master’s student of accounting and corporate finance, I intend to seek internship in global investment banking firms. M&A activities are at the sharp focus of a large number of such firms. The study will allow me to achieve a rewarding career in the long run. In this light, further recommendations for present study are

- Analysis of statistical terms like Beta to learn about cost of equity capital. This paper lacks a focus on stock market analysis because the pattern of study was based on descriptive statistics and not case study. A case study approach would give this paper more individualised, meaningful depth.

- Agency costs for M&A activities should be used to calculate valuation for various stocks in a given market scenario.

References

Agarwal, A., (1981). Managerial Incentives and Corporate Investment and Financing Decisions. Journal of Finance. Vol.17, No.4.

Allen, S.G., (1981), Pensions and Firm Performance. National Bureau of Economic Research. Madison, WI.

Antle, R. & Smith, A., (1986). An Empirical Investigation of the Relative Performance Evaluation of Corporate Executives. Journal of Accounting Research. Vol. 24, No.1.

Bakir, C., (2005). The Exoteric Politics of Bank Mergers in Australia. The Australian Journal of Politics and History. Vol.51.

Buhner, J., (1990). Globalisation and Strategic Concepts (German: translation). Gabler, Hannover (West Germany).

Bundesbank, (2007). Special Statistical Publication 5: extrapolated results from financial statements of German Enterprises. Web.

Business Week, (2003). Daimler-Chrysler Stalled. Business Week Online. Web.

Car and Driver, (2007). Chrysler Announces Major Downsizing. Web.

Chandler, A.D., (1990). Scale and Scope, Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA.

Coleman, J.S., (1990). Foundations of Social Theory. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA.

Demski, J.S., Patell, J.M., & Wolfson, M.A., (1984). Decentralised Choice of Monitoring Systems. The Accounting Review –JSTOR. Vol.59. No.1.

Dyl, E.A. (1988). Corporate Control and Management Compensation: Evidence on the Agency Problem. Managerial and Decision Economics. Vol.9, No.1.

Drobetz, W., (2003). Corporate Governance: Legal Friction or Economic Reality. University of Basel: Department of Finance (Working Paper)

Eisenhardt, K.M., (1989). Agency Theory: An Assessment and Review. Academy of Management Review, 57-74.

Feils, D.J., (1993). Shareholder Wealth Effects of International Mergers and Acquisitions: Evidence from the United States, United Kingdom and Germany. Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 25.

Fin Facts Ireland, (2007). Global M&A Predicted to Peak in 2008, Smashing through the $5 trillion Glass Ceiling. Web.

Financial Times Team, (2007). Germany is fourth largest M&A destination. Financial Times, London.

Frensch, F., (2007). The Social Side of Mergers and Acquisitions: Cooperation Relationships. DUV, Paris.

Gropelli, A.A., (2000). Finance, 4th Edn. Barron’s Educational Series. 433.

Grossman, S. & Hart, O., (1983). An Analysis of the Principal Agent Problem. Econometrica. Vol.51, No.1.

Herman, E.S., (1981). Corporate Control, Corporate Power. Cambridge University Press. (Cambridge and New York).

Hinkin, T. (1987). Managerial Control, Performance and Executive Compensation. Academy of Management Journal. Vol.6, No.9

Hitt, M.A., Harrison, J.S. & Ireland, R.D., (2001). Mergers and Acquisitions: A Guide to Creating Value for Shareholders. Oxford University Press, London. p. 4-7.

Holmstrom, B., (1979). On the Theory of Delegation. Center for Mathematical Studies in Economics and Management Science at Northwestern University. Web.

Höpner, M. & Jackson, G., (2003). An Emerging Market for Corporate Control? The Mannesmann Takeover and German Corporate Governance. Max Planck Institute of Corporate Governance (German translation). Köln, Germany.

Jensen, M.C., (1986). Agency Cost of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance and Takeover. American Economic Review. Vol. 17.

Kroll, M., Simmons, J. & Wright, P., (1989). Form of Control: A Critical Determinant of Acquisition Performance and CEO Rewards. School of Business Administration: University of Texas.

Lambert, R.A., (1983). Long-term Contracts and Moral Hazards. The Bell Journal of Economics. Vol.14, No.2.

Lazear, E.P. & Rosen, S., (1981). Rank Order Tournaments as Optimum Labour Contracts. The Journal of Political Economy. Vol.89, No.5.

Macdonald, E.H., (2001). GIS in Banking: Evaluation of Canadian Mergers. Canadian Journal of Regional Science. Vol.24.

Malatesta, C., (1983). Affect and the Research Agenda: K-Vexing about the States of Emotion Research. American Psychology Publication (APA). Vol.3.

McEachern, W.A., (1975). Managerial Incentives and Firm Performance under Three Different Control Conditions. Doctoral Dissertation: University of Virginia.

Mirrlees, J.A., (1976). Optimal Tax Theories: A Synthesis. Working Papers: MIT, Department of Economics.

Murphy, K.J., (1986). Executive Compensation. Web.

Palmer, D. & Barber, B.M., (2001). Challengers, Elites and Owning Families: A Social Class Theory of Corporate Acquisitions in the 1960’s. Journal of Administrative Science Quarterly. Vol.24.

Peck, S. & Temple, P., (2002). Mergers and Acquisitions: Critical Perspectives on Business and Management. Taylor and Francies, Louisville, KY.

Pfeffer, J., (1980). Organisation Theory and Structural Perspectives on Management. Journal of Management. Vol.17, No.4.

Ravenscraft, D.J. & Scherer, (1987). Mergers, Sell-offs and Economic Efficiency. The Brookings Institution, Washington DC.

Roberts, D.R., (1959). A General Theory of Executive Compensation Based on Statistically-Tested Propositions. Glencoe: The Free Press.

Rothschild, (2008). NM Rothschild and Sons Ltd. Ratings Report. Rothschild Inc.