Introduction

Background to the Study

The composition of the global workforce, especially in the services sector, has changed significantly over the last few decades. One of the core transformations, it seems, has been the increase in the number of short-term employees working in services-oriented organizations (Jacobsen 2000). A strand of existing literature (e.g., De Gilder 2003; Burgess & Connell 2006; Haden, Caruth & Oyler 2011) demonstrates that the utilization of temporary workers to fulfill staffing requirements is a practice that gained prominence in the 1990s and is being executed by an estimated nine out of ten services-oriented organizations doing business in the United States. Overall, the number of temporary workers employed in all sectors of the United States economy is staggering. In 2005, for instance, official statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics revealed that contingent employees (i.e., temporary and part-time employees, outsourced contractors and subcontractors, contract employees, and university interns) comprised 26 percent of the total workforce in the United States, with an estimated 1.2 million people being categorized as temporary workers (Haden et al 2011).

There are several justifications why organizational managers settle on temporary employees and this type of staffing strategy. Undoubtedly, the most substantial justification is the mounting demand for labor flexibility, both from the organizations and from organizations (Haden et al 2011). Additionally, human resource literature demonstrates that enterprises engage temporary workers not only to cut labor costs and manage the temporary absence of core staff (Van Breugel, Olffen & Olie 2005) but also to access the opportunity to screen employees for permanent positions within the organization (Burgess & Connell 2006).

Despite the considerable increase in temporary work in the services sector (Van Breugel et al 2005; Haden et al 2011), there has been comparatively minimal theoretical and empirical work set to understand the ramifications of the shifts in the organization’s labor force on work commitment (Jacobsen 2000; Johnson, Change & Yang 2010). Moreover, it remains unclear which specific forms of commitment should be addressed in practice when dealing with temporary employees since management studies (e.g., Biggs & Swailes 2006; De Cuyper & De Witte 2007) have shown their work behaviors and motivating factors to be substantially different from those of core staff. The purpose of the present study is to expand the current knowledge on these cardinal issues, by comparing the work commitment for permanent workers and temporary workers who perform comparable jobs in a hotel setting. A further aim, which is related to the first, would be to investigate to what degree job status (permanent versus temporary) play a role in the emergence of work commitment; that is, whether or not job status informs or influences the level of work commitment an organization gets from employees.

Scholars have found it difficult to define commitment because the term has been obscured by definitional ambiguity and inconsistency (Klein, Molly & Brinsfield 2012), and attempts to provide an all-inclusive definition have not been fully leveraged through a shared comprehension of what commitment is and how it operates (Haden et al 2011). In this light, extant literature demonstrates that the same operationalization of the notion of commitment has stood for almost three decades, yet the working and competitive environments have shifted tremendously since then (Singh & Vinnicombe 2000). However, it is suggested in the management literature that committed employees to contribute to the organization in more productive ways than less committed employees (Crawford & Hubbard 2008), and that the commitment that employees have toward their organization and its constituents is a critically fundamental work attitude (Johnson et al 2010). It is with this predisposition that the current project attempts to critically analyze the work commitment levels for permanent versus temporary employees at Jing Jiang Tower Hotel, Shanghai.

The Study Context

Opened in 1990 to a rousing welcome and achieving a five-star status a year later (Jin Jiang Tower 2012a), the Shanghai Jin Jiang Hotel is ideally positioned in the former French concession close to the Huai Hai Road Central Business District, and thus attracts plenty of foreign dignitaries, tourists and businessmen due to its convenient traffic and exquisite oriental-attentive services (ChinaTour.Net 2010; Jin Jiang Tower 2012b). As a flagship hotel facility of Jin Jiang Hotels Conglomeration, the largest hotel group in China and Asia, the 43-storey hotel is one of the outstanding sites to overlook the beautiful Shanghai downtown landscape and is further catapulted to star status by the fact that it has hosted more than 370 heads of states, international dignitaries and celebrities since its inception. The notable guests’ list includes the presidents of the United States, France, United Kingdom, Germany, Israel, Singapore, and the Republic of Korea, as well as the general secretary of the United Nations (Jin Jiang Tower 2012b). The hotel has a huge pool of highly qualified permanent members of staff but routinely provides employment to temporary workers and college interns depending on need and season (He, Lai & Lu 2011).

China is of theoretical, as well as practical significance, and presents an ideal environment and context for the study of work commitment for permanent and temporary employees. There are two reasons that inform the choice of China. First, there is an interesting trend that results in atypical challenges for organizations doing business in China. With the mounting inflation and cut-throat competition for talents and skills in the marketplace, numerous Chinese enterprises have increased their workers’ remuneration packages. Nonetheless, according to He et al (2011, p. 198), “…an investigation conducted by Hande Consultant Co. in 2007 showed that 47% of companies reported that the employee turnover was still above 10%, and 13% of companies reported that employee turnover rate was as high as 20%.” The high level of employee turnover in China, as noted by these authors, is substantially upsetting organizational competitiveness and productivity.

The second reason for the choice of China rests on the premise that the country is transiting from a planned economy to a market economy (He et al 2011), and is experiencing rapid shifts in political, economic, and social contexts, which may appreciably influence organizational and employee behaviors (Sheng, Zhou & Li 2011). Allen and Meyer (1996) cited in He et al (2011, p. 201) suggest that “…the issue of commitment is particularly important for managers in organizations which are experiencing change at increasing speed and scale in their external and internal environments” Since the services sector is at the core of these shifts (Crawford & Hubbard 2008), it becomes plausible to investigate the work commitment for permanent and temporary employees working in Chinese hotels, with the view to spur positive organizational and employee behaviors.

Statement of the Problem

The study of commitment in the workplace came into the limelight in the 1960s and was grounded at first on the concept of organizational commitment (Cohen 2011). Today, as noted by this author, academics and practitioners recognize that workers are exposed concurrently to more than one entity of commitment. The multiple-commitments paradigm identifies a multiplicity of commitment foci other than the basal organization, both broader in context (i.e., the occupation, the labor union, work in general), and more specific (i.e., performance, satisfaction, cognitive withdrawal, workgroup, one’s particular job, and turnover) (Johnson et al 2010; Cohen 2011). Additionally, diverse justifications underlie why workers are committed – for example, they may identify with the objectives and mission statements advocated by the organization, or they may value the job security, training opportunities, and remuneration packages tied to their membership (Johnson et al 2010).

Extant management literature demonstrates that “…the increasingly competitive service sector is always looking for employees who can perform well while providing a superior level of service quality” (Crawford & Hubbard 2008, p. 117). One factor in the literature that has been demonstrated to influence performance and turnover, as well as organizational and employee behaviors, is commitment (De Gilder 2003; Freud & Carmeli 2003). In equal measure, current human resource practices demonstrate a marked deviation from the use of permanent staff to the engagement of temporary and contract workers to fulfill the staffing requirements of organizations (Burgess & Connell 2006), and in particular service-oriented establishments (He et al 2011). At present, however, there is an inadequate industry-wide snapshot of how job status (permanent versus temporary) influences work commitment in service-oriented settings, and if work commitment acts as an antecedent to turnover and employee behavior when evaluated through the lens of job status. It is believed that learning more about the relationship between these constructs might help in providing organizations with a framework through which they could make use of temporary employees and still remain competitive and productive. Consequently, a rigorous quantitative descriptive study is needed to provide solutions to the highlighted gaps in knowledge.

Aim & Objectives of the Study

The general aim of this study is to critically analyze the work commitment for permanent versus temporary employees at Jing Jiang Tower Hotel, Shanghai. The following forms the specific objectives of the study:

- To expand the current knowledge on work commitment among permanent and temporary members of staff in a hotel setting;

- To ascertain what degree job status (permanent and temporary) plays in informing the emergence of work commitment;

- To critically evaluate the interplay between job status and work commitment in informing employee turnover intentions;

- To compare and contrast how to work commitment across the two job statuses (permanent and temporary) influence organizational and employee behaviors, and;

- To analyze and report on probable alternatives that could be used by industry to strengthen work commitment levels for permanent and temporary workers.

Research Questions

Based on the mentioned objectives, the present study aims to address the following key research questions:

- What are the current practices and policies used by firms within the hotel industry to influence work commitment among permanent and temporary workers?

- How does job status informs the emergence, growth, and actualization of work commitment among permanent and temporary workers in a hotel setting?

- What issues within the job status context could be serving as obstacles to the realization of work commitment among permanent and temporary workers, leading to turnover?

- To what extent does work commitment influence organizational and employee behaviors across the two job statuses; that is, permanent and temporary workers?

Significance of the Study

The present study makes several contributions to the management literature. First, it provides managers in the hotel and hospitality domain with current knowledge on how to spur work commitment among permanent and temporary workers for the sustenance of competitive advantage and productivity. Second, the study enriches our understanding of how job status informs the emergence and progression of work commitment. Such knowledge, according to Haden et al (2011), is important in informing human resource policy directions as organizations increasingly rely on temporary employees to get the job done. Third, and perhaps most important, it is a well-known fact that most of the existing studies on commitment were undertaken in western contexts, in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom (Elizur 1996; De Gilder 2003; He et al 2011; ). The generalizability of these findings may be put to question, in large part due to the fact that cultural variations do play an essential role in informing the antecedents and consequences of work commitment (He at al 2011). Therefore, the evidence from the hotel industry of China in the present study will go a long way to fill this gap.

Scope of the Study

There are various types and forms of commitment. The present study concerns itself with only one type, namely work commitment. This implies that the study will exclude the analyses of other types of commitment, including organizational and group commitment. Additionally, there exist various types of employees under the umbrella of contingent workers, such as temporary workers, contract workers, sub-contractors, and outsourced staff (Haden et al 2011). The analyses of the present paper will be limited to temporary workers only. Lastly, data were collected in one hotel facility through an online survey; however, it is assumed that the data were representative of the hotel industry in China, and therefore, results could be generalized to other hotel facilities within the services sector.

Structure of the Dissertation

Chapter one has laid the groundwork for the study by discussing the background to the study, the study context and problem discussion, as well as the aim and objectives of the study, key research questions, and significance and scope of the study. Chapter two undertakes a critical analysis of existing relevant literature and theories on work commitment and related concepts. Chapter three discusses the methodology of the study, including issues of the study design, population and sample, data collection approaches, ethical considerations, and data analysis techniques. The results of the study, along with their discussion, are presented in chapter four. The study terminates by outlining and briefly discussing some conclusions and recommendations in chapter five.

Literature Review

Introduction

The present study seeks to critically analyze the work commitment levels for permanent and temporary workers in a hotel setting. This section, among other things, undertakes a critical analysis of the existing literature on work commitment and other issues considered as antecedents or consequents to the broad topic of commitment. Apart from analyzing several theoretical underpinning to the study of commitment, key among them the psychological contract, this section also analyzes current and relevant literature on some issues of interest, including job status and work commitment, turnover and work commitment, employee behavior, and work commitment, as well as work commitment, issues predominant in the hotel and hospitality industry.

Understanding the Concept of Commitment

Werkmeister (1967) cited in Elizur (1996) defined commitment as a manifestation of the person’s own self, and reflects value prepositions as well as standards that are core to the individual’s existence as a person. Porter et al (1974) cited in Van Breugel et al (2005, p. 542) defined commitment in terms of “…the strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization.” Commitment, especially organizational commitment, and work commitment is one of the most extensively researched issues in the study of organizational behavior (Johnson et al 2010) and has been analyzed from multiple points of view (Steenbergen & Ellemers 2009). Extant literature demonstrates that, in nearly all domains and sectors of the economy, the commitment continues to be “systematically linked to lower absenteeism, turnover and turnover intentions, as well as higher job satisfaction, organizational citizenship and job performance” (van Breugel et al 2005, p. 539).

Commitment, as it is known today, is characterized by three core aspects. First, organizationally committed workers to believe in and accept their organizational goals and values, and act to meet them through their demonstrated work behaviors and plans. Second, organizationally committed workers to have a unique readiness to exert effort towards organizational goal achievement, and third, these employees demonstrate a strong aspiration to preserve organizational bond and membership (Van Breugel et al 2005). Klein et al (2012) postulate that the bond that acts to maintain organizational membership in committed workers can be described in terms of volition, dedication, and responsibility. Using this lens of analysis, commitment is conceptualized in the management literature as an affective or emotional attachment to the work carried out by the organization (work commitment), or to the organization itself (organizational commitment) (Chon et al 1999; Van Breugel et al 2005). It, therefore, follows that workers form a bond with their work or with an organization based on their unique emotional feelings towards these entities.

As noted by Elizur (1996, p. 26), commitment “…has served as both a dependent variable for antecedents such as age, tenure, gender, and education and as a predictor of various outcomes such as turnover, intention to leave and absenteeism.” In a study on reconceptualizing workplace commitment, Klein et al (2012) proved the existence of many relationships between commitment and important individual and organizational outcomes, such as motivation, performance, turnover, and wellbeing. Extending this view, McKeown (2003), concurs that the concept of commitment is a traditional area of human resource management (HRM) concern and, certainly, the real justification for introducing HRM policies in an organization is to enhance levels of commitment so that other positive employee and organizational outcomes can follow. As acknowledged by this particular author, it is this conjecture which inspires the popular employer affirmation that “employees are our most valuable resource.”

Commitment within the Work Domain

A strand of existing literature (e.g., Miller et al 2002; Meldrum & McCarville 2010) shows that the quality of services in the hotel and hospitality sector depends on a number of variables, including but not limited to, work commitment, job satisfaction, job involvement, and morale. This view is reinforced by Carmeli, Elizur, and Yaniv (2007), who argue that work commitment has been demonstrated to affect performance and, consequently, practitioners must always strive to construct a deeper understanding of worker concerns and the unique characteristics of workers who drive organizational performance through their commitment approaches. On their part, Nath and Raheja (2001) note that studies on the service profit chain have demonstrated how important committed workers are to an organization’s overall growth strategy and performance. In their study on competencies in the hospitality industry, Nath and Raheja (2001) show a link between employee work commitment and the service concept, directly impacting customer satisfaction and repurchase behavior. Such a business orientation, according to Crawford and Hubbard (2008), affects customer loyalty, which in turn influences organizational competitiveness and revenue growth.

To better understand work commitment, it is imperative that various forms of commitment be analyzed. Extant management literature demonstrates that commitment is normally conceptualized as a multidimensional phenomenon, consisting of multiple forms – affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment (Singh & Vinnicombe 2000). The first form, affective commitment, “…entails an acceptance and internalization of the other party’s goals and values, a willingness to exert effort on that party’s behalf, and a strong attachment to that party” (Johnson et al 2010, p. 227). In the work context, Meldrum & McCarville (2010) argue that this type of commitment can be formed through self-determined motivations from the workers, which reflects independent tendencies to engage in goal-directed actions because they are believed to be significant in and of themselves.

Contributing to this domain of research, Steenbergen, and Ellemers (2009) note that explicit self-determined motivations that inspire affective commitment in the process of influencing work commitment include identification and internalization. Identification reflects a craving for affiliation on the part of employees, which then causes them to align their self-identity with the work processes and the organization (Lam et al 2003; Crawford & Hubbard 2008; Johnson et al 2010), and demonstrate behaviors that are consistent with work-related as well as organizational expectations (De Cuyper & De Witte 2007). Internalization occurs when the values and objectives of the workers become congruent with those of the work processes as well as the organization (Johnson et al 2010), because these employees have incorporated them into their self-concepts (Singh & Vinnicombe 2000; Gonzalez & Garazo 2006).

A second form is a normative commitment, “…which entails perceived obligations to maintain employment memberships and relationships” (Johnson et al 2010, p. 227). A strand of existing literature (e.g., Steenbergen & Ellemers 2009; Cohen 2011) demonstrates that in the exchange for employment and other benefits that come with it, including commissions, salaries, and other perks, workers feel obliged to respond with loyalty and commitment that originate from morality and value-oriented standards grounded on reciprocity norms and socialization practices. Van Breugel et al (2005) refer to this form as moral commitment, essentially implying a sense of obligation demonstrated by the worker to remain with the organization.

Normative commitment is not only less organization-specific than affective commitment, in large part because workers’ levels of the former type are affected more by cultural socialization and general beliefs regarding employment than by actual experiences with an explicit organization (De Cuyper & De Witte 2007), but it is characterized by introjection rather than identification or internalization (Meyer et al 1997; Johnson et al 2010). In work-related contexts, it is suggested by these authors that introjection is in operation every time a worker accomplishes obligations, with the view to reduce feelings of guilt and anxiety. The difference between the two forms is thus clear in that felt obligations and emotional experiences, including feelings of guilt and anxiety, are internal constraints on behavior that are uniquely distinct from external constraints, such as promotions and monetary recompenses (Johnson et al 2010). An important point floated by these authors is that introjection demonstrates minimal self-determination principles than both identification and internalization, and, consequently, compared to affective commitment, normative commitment has fragile relationships with enviable work-related behaviors, including work attendance and task performance.

More recently, as suggested by Van Breugel et al (2005), researchers have identified a third form known as continuance or calculative commitment, which differs in its psychological state, the antecedent conditions leading to its development, and the behaviors that follow from its characteristics. Continuance or calculative commitment is a type of psychological attachment to an employer, which illuminates the level to which a worker experiences a sense of being locked in place due to myriad factors – key among them being the soaring costs of leaving. Johnson et al (2010) acknowledge that such investments may be of financial nature (e.g., paid holidays, paid doctor visits, retirement packages, paid annual leaves, job security), or non-financial nature (e.g., good management style, responsive organizational structure, organizational goals, friendship with other employees, status). Meyer and Allen (1984) cited in Johnson et al (2010) argue that this form of commitment entails appraisals of individual investments tied to one’s current employment and the accessibility of employment options.

Contributing further to this debate, Cohen (2011) argues that continuance or calculative commitment is a form of the motivational phenomenon, in large part because it entails self-regulatory sequences such as identification, internalization, and compliance. This view is reinforced by Johnson et al (2010), who argue that workers demonstrating a strong continuance/calculative commitment maintain their current employment since it avails them with enviable individual outcomes that they are reluctant to sacrifice or because they recognize a lack of employment openings elsewhere. One major characteristic of this form of commitment is compliance, which, in work-related contexts, entails behaviors that are initiated and maintained by workers with the view to gratify exterior constraints, such as acquiring a reward or evading a loss (Steenbergen & Ellemers 2009).

It is imperative to note that because of the fact that continuance commitment originates principally from external constraints (e.g., rewards and reprimands conveyed by leaders), this form of commitment is not self-determined; however the ends themselves may be fundamentally desirable (e.g., job opportunities for personal and professional growth), and appreciated for justifications other than compliance-based motivations (e.g., working hard to earn bonuses to satisfy familial responsibilities; Johnson et al 2010). Consequently, management literature shows that continuance commitment in work-oriented contexts bears weak or negative relationships with desirable job behaviors (e.g., attendance, citizenship behaviors), particularly due to the fact that its fundamental compliance motivation is minimally self-determined than other constructs, notably identification, internalization, and introjection (Yousef 1998; McDonald & Makin 2000; Johnson et al 2010).

Theoretical Underpinnings of Commitment

Extant literature demonstrates that commitment theory is grounded on reciprocity theory, which “…essentially states that when one person treats another person favorably then the norm of reciprocity stimulates a proportional return” (Biggs & Swailes 2006). In organizational as well as work-oriented contexts, positive treatment from an employer in the form of respect, provision of favorable work environment, consideration, or financial and non-financial resources afforded to the worker should be reciprocated in the form of positive attitudes and work-oriented effort.

Another theory – organization support theory – acknowledges that workers hold perceptions about how much their employer values their contribution (Biggs & Swailes 2006), as well as how the employer care about them as individuals; that is, whether the employer is concerned about the workers’ sense of (dis)satisfaction with some characteristics of their working life (Cohen 2011). This theory further presupposes that in instances where workers feel that organizations do care about their plight and do indeed value them in their individual contributions, then this gesture should be reciprocated through a commitment to the organization’s objectives (organizational commitment), as well as through work performance (work commitment) and positive behavior.

The last concept under consideration is the psychological contract, which, in organizational and work-related contexts, denotes the fairness or balance between 1) how the worker is treated by the employing entity, and 2) what the worker puts into a particular job situation (Raulapati, Vipparthi & Neti, 2010). Cohen (2011, p. 648) defines the psychological contract “…as an unwritten agreement between an individual and the organization about the terms of employment, signaling expectations about issues of exchange and obligation on both sides.” The psychological contract can enhance our comprehension of commitment, especially work commitment, to the extent that it is grounded on the concept of exchange (Jafri 2011), with available empirical findings demonstrating that the type of psychological contract, as well as infringements of such contracts, influence workers’ attitudes and behaviors such as commitment, performance, productivity, turnover, and extra-role performance (Cohen 2011). Research demonstrates that the nature of current employment trends, typified by an increase in temporary employment (Bulut & Culha 2010) and loss of job security (Carmeli et al 2007) have not only resulted in a redefinition of career expectations and the nature of the employment relationship but is increasingly triggering psychological contract breaches, resulting in numerous adverse job-related behaviors for the organization such as diminished commitment, reduced citizenship behavior, lowered worker trust, as well as enhanced likelihood to leave the organization (McDonald & Makin 2000; Lewis 2011).

Changing Trends in Modern-Day Workforce

In recent decades, there has been a noted shift in the workforce composition, from an overreliance on permanent workers to the provision of numerous opportunities for temporary employees (Haden et al 2011). Indeed, available literature demonstrates that temporary work was the most rapid type of atypical employment in the 1990s, doubling its share in most EU member countries (Van Breugel et al 2005), and dramatically changing the composition and landscape of American organizations (Haden et al 2011). Today, a substantial component of the workforce comprises temporary workers – individuals who are ready and willing to perform a job for the organization on the basis of a contract of the strictly limited duration of maybe a week, a month, six months, or more (De Gilder 2003). This particular author further posits that whatever the lifespan of their contract is, temporary employees know that the relationship with their organization and with their work colleagues, in principle, will terminate at a time they generally know when they commence their job. Such knowledge, according to Burgess and Connell (2006), bears far-reaching consequences on their work commitment and performance.

There exist a multiplicity of justifications why organizational managers make a decision to utilize temporary employees and this type of staffing strategy. Temporary employment arrangements, according to Haden et al (2011, p. 145), “…allow organizations to supplement their core workforces, adding the flexibility often needed in an environment of fluctuating labor demands.” Additionally, temporary arrangements not only grant the capacity to minimize labor costs, safeguard the job security of permanent workers, and serve as an effective way to screen employees for permanent positions (De Gilder 2003; Rosendaal 2003; Haden et al 2011), but they provide temporary workers with the much-needed work experience, thus improving their employability ratings (Burgess & Connell 2006). It is also reported in the literature that an increasing number of individuals are resorting to temporary work with the view to gratify particular individual needs and preferences, such as the opportunity to sample diverse organizations and employers, or a need for job diversity, time flexibility or shorter-term obligations (Van Breugel et al 2005).

Job Status & Work Commitment

Job status is taken here to mean either permanent or temporary employment. Gallagher and McLean (2001) cited in Van Breugel et al (2005) note that the majority of current research has studied the concept of commitment in the context of a continuous, ongoing employment relationship known as permanent employment. This assertion imply that considerably less research has centered on work commitment in more flexible and temporary employment arrangements, such as is widespread in the rapidly expanding temporary work placements, especially in the services sector. Yet, such an analysis is important since temporary work arrangements (described in terms of varying from nonessential, alternative, contingent to atypical and non-standard) are increasingly becoming the norm rather than the exception (McKeown 2003).

Extant management literature shows that the existence of temporary work arrangements remove one of the basics motivating work commitment – that of the substitution of commitment for ongoing employment security (McKeown 2003). Extending this thread of thought, () argues that the organization’s treatment of temporary workers has been found to influence the perception and commitment of permanent members of the workforce. In their informative study on “job insecurity in temporary versus permanent employees”, De Cuyper and De Witte (2007) noted that enhancing the ratio of temporary workers in the organization, in turn, dwindles the levels of organizational trust and work commitment of permanent workers. Another study by Pearce (1993) cited in McKeown (2003) supports this finding, but also revealed that temporary workers aggressively took part in extra pro-social behavior in obvious efforts to “fit in” with the employing entity – perhaps to achieve permanent employment status.

The Hotel Industry & Work Commitment Issues

The hotel industry today, as is the case in many other services-oriented businesses, is a diverse composite of ownership prototypes, varying management arrangements and which provide a multiplicity of services. In this industry, it is becoming increasingly important that employees – permanent and temporary – work towards realizing and maintaining differential competitive positioning grounded on the provision of excellent service standards (Nath & Raheja 2001). This proposition is reinforced by Crawford and Hubbard (2008, p. 116), who acknowledges that “…the increasingly competitive service sector is always looking for employees who can perform well while providing a superior level of service quality.” One factor in the literature that has been demonstrated to influence performance in this way is work commitment (Klein 2012). Indeed, a meta-analysis done by Kini and Hobson (2002) and cited in Crawford and Hubbard (2008) revealed that work commitment in the hotel industry shares a relationship with intrinsic work satisfaction, goal-setting behavior and job involvement, intrinsic total quality initiatives, intention to quit, and organization-based self-esteem.

The hotel industry is in a constant mode of change, to remain abreast of the myriad challenges affecting its external as well as the internal environment (Crawford & Hubbard, 2008). The industry, for example, is currently engaged in a shift away from overreliance on permanent workers, not only to cut down on mounting labor costs but also to maintain flexibility and manage the temporary absence of core members of staff (Van Breugel et al 2005). A strand of existing literature (e.g., Burgess & Connell 2006; Bulut & Culha 2010; Cohen 2011) demonstrates that a foremost aspect in driving the preferred behaviors in the organization is how the changed strategies, processes, and innovative concepts are implemented and communicated to employees down the line. This aspect, according to Nath and Raheja (2001), is of fundamental significance as a shift in the job status due to changed processes obliges a different competency requirement on the part of the job incumbents, leading to differential skill sets and performance measurement standards. Here arises the urgent need for a common thread that would run across all human resource systems in the organization, with the view to assist organizational leaders to drive and measure the work commitment of individual employees, especially temporary workers (Burgess & Connell 2006). Hospitality and leisure management literature show that although academic aptitude and knowledge content do not predict job performance or success (Nath & Raheja 2001), work commitment does, in part due to its capacity to help employees create value and reinforce positive organizational and individual behaviors (Meldrum & McCarville 2010).

Summary

Commitment is typified by three core principles – belief in and accepting of organizational goals and values, unique readiness to exert effort towards goal achievement, and a strong aspiration to preserve organizational bond and membership. Commitment has served as a dependent variable for precursors such as age, tenure/job status, sex, and educational standing, and as a forecaster of a multiplicity of outcomes, including job involvement, turnover and quit intentions, on-the-job performance and productivity, employee health and well-being, as well as absenteeism. Available literature demonstrates that commitment is normally conceptualized as a multidimensional phenomenon, consisting of multiple forms – affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment (Singh & Vinnicombe 2000).

The quality of services in the hotel and hospitality sector depends on a number of variables, including but not limited to, work commitment, job satisfaction, job involvement, and morale. Studies on the service profit chain have demonstrated that committed workers not only directly impact customer satisfaction and repurchase behavior, but they are the driving force behind are an organization’s overall growth strategy and performance (Nath & Raheja 2001).

In organizational contexts, it has been shown that recently, there has been a noted shift in the workforce composition, from an overreliance on permanent workers to the provision of opportunities for temporary employees. Temporary work arrangements not only permit organizations to supplement their basic workforce and afford the flexibility often required in the context of irregular labor demands, but also minimize labor costs, safeguard job security of permanent staff, and serve as an effective way to screen employees for permanent positions.

However, considerably less research has centered on work commitment in more flexible and temporary employment arrangements, such as is widespread in the rapidly expanding temporary work placements, especially in the services sector. Collecting and analyzing data on work commitment for permanent versus temporary workers, especially in the context of the services, is an important milestone since temporary work arrangements are increasingly becoming the norm rather than the exception. It is this comprehension of facts that provides the impetus for chapter three, which aims to demonstrate the techniques used to collect data for the present study.

Methodology

Introduction

Chapter 3 purposes to provide information on how the study has been conducted, in addition to outlining the justifications for using the mentioned methodologies and procedures. The section discusses (a) the research design used in the study, (b) population and sample, (c) data-gathering instruments, (d) issues on reliability and validity, (e) ethical considerations for the study, and (f) data analysis procedures.

Research Design

The present study, which is quantitative in approach, utilizes a descriptive research (survey research) design to critically analyze work commitment levels for permanent versus temporary workers in a hotel setting. Available literature demonstrates that quantitative methods can utilize three research designs, namely descriptive, correlational and causal-comparative, to collect and analyze numerical data acquired from formal instruments (Creswell 2002; Sekaran 2006). Descriptive research involves not only identifying the unique characteristics of an observed phenomenon or sets of phenomena but also examining the situation as it is without changing or modifying it (Creswell 2002).

Consequently, the descriptive/survey research design selected for the study receives justification from the perspective that it assisted the researcher to acquire important information about the groups under investigation (permanent and temporary workers), including their characteristics, opinions, values, attitudes, expectations, or previous experiences, by simply posing questions to them and tabulating their responses (Philips & Starwaski 2008). A second justification is grounded on the fact the descriptive/survey research design enabled the researcher to learn about a large population (permanent and temporary workers in the hotel industry) by surveying a sample of permanent and temporary employees at Jing Jiang Tower Hotel, Shanghai.

Extant literature shows that a descriptive/survey research characteristically uses a face-to-face interview, a telephone interview, or a previously written and pretested questionnaire instrument (Sekaran 2006). It is important to mention that the present study employs an online questionnaire schedule requiring participants to respond to a series of statements or questions about themselves through the self-report technique. Although the self-report technique is easy to use, less costly to manage and provides participants with the flexibility to respond to the questions (Bryman & Bell 2007), it runs the risk of intentional data misrepresentation as some people may only be interested in creating a favorable impression to the researcher rather than outlining the “facts” as they know them (Creswell 2002).

Target Population & Sample

The target population for this study comprises employees working in the hotel and hospitality industry. Specifically, the study targets both permanent and temporary employees working in the hotel industry within the Chinese context. The justification for selecting this population is premised on two interrelated facts, namely (1) temporary work is increasingly gaining prominence in the services-oriented sector (Van Breugel et al 2005), thus the need to understand the variables that influence this group of the labor force to become more committed to their work, and (2) Available literature demonstrates a divergence of triggers and consequences of work commitment among permanent and temporary workers (De Cuyper & De Witte 2007), thus the need to evaluate the two groups to note points of divergences.

It is imperative to note that the researcher uses online protocols to identify a pool of permanent and temporary employees working at Jing Jiang Tower Hotel, after which purposive sampling technique is used to select a sample of 80 participants – 40 permanent employees and 40 temporary employees – for purposes of data collection. As postulated by Sekaran (2006), respondents in a purposive sample are selected to take part in a study based on two factors, namely (1) compatibility to the study aim and objectives, and (2) demonstrated comprehensive understanding about the phenomena under investigation. Consequently, the justification for using this sampling technique is premised on the fact that the researcher receives responses rich in context as well as scope because participates have demonstrated knowledge and understanding about the topic of interest.

The Sampling Criteria

Since the study is knowledge- and job status-specific, the participants had to meet all of the following standards to be allowed participation:

- Must be between 18 and 55 years;

- Permanent workers must have worked in the hotel industry for a period not less than 5 years;

- Temporary workers must have worked cumulatively for a period not less than 1 year;

- May be of either gender, but conversant with issues affecting productivity and performance in the hotel industry;

- Must demonstrate sufficient understanding of the problem under investigation, and;

- Must be ready and willing to take part in the online survey.

Data Gathering Instruments

The questionnaire is used in this study as the primary data gathering instrument for permanent as well as temporary workers of the hotel. It is important to note that Mowdy, Steers and Porter (1979) organizational commitment questionnaire, cited in Carmeli et al (2007), has been adopted and modified to collect data on work commitment rather than organizational commitment. The questionnaire, containing 15 items (scaled, ranked, checklist, and free-response), underwent pretesting prior to the commencement of the data collection exercise, not only to gather information about deficiencies and propositions for improving the instrument but also to ensure that it provides greater content validity upon exposure to participants in the field (Phillips & Starwaski 2008). The instrument was first prepared in the English language but later translated to the Chinese language to ensure that workers who did not understand English also participated in the research. Secondary data for the present study is gathered through a critical analysis of relevant literature, which is important to any research process since it represents a reflection of reality (Sekaran 2006).

The questionnaire, administered using online platforms, contains items of different layouts, including but not limited to multiple-choice questions; asking either for a single choice or all that apply; dichotomous responses such as “Yes” and “No”; self-evaluation items assessed on a 5-point Lickert type scale, and; open-ended items that cannot be holistically captured by closed-ended items (Phillips & Starwaski 2008). The rationale for selecting the questionnaire as the principal data collection instrument for the study revolves around issues of cost-effectiveness when administered via online platforms (Bryman & Bell 2007), ease of application and adaptability (Sekaran 2006), ability to guarantee the anonymity of respondents, as well as liberty to incorporate unstructured items in the pursuit of new information or new horizons of knowledge, which may be unknown to the researcher (Phillips & Starwaski 2008).

Reliability and Validity

In quantitative research, the reliability of the measuring instrument (survey questionnaire) is of massive significance as it acts to reduce errors largely associated with the use of faulty measurement parameters (Balnoves & Caputi, 2001). Reliability, which essentially refers to the exactness and correctness of a measurement technique (Philips & Starwaski, 2008), shows that the same set of study findings would have been collected from the field each time in repeat evaluations of an identical variable or phenomenon of interest, otherwise statistically referred to as consistency of measurement (Sekaran, 2006). Reliability of the study findings has been achieved by (1) pilot-testing the questionnaire schedule, (2) making sure that measures incorporated into the questionnaire instrument only capture data that is of interest to the main topic under investigation, (3) employing multiple indicators to guarantee the collection of quality unabridged data from the field, and (4) increasing the range of measurement of the questionnaire instrument (Creswell, 2002).

Validity in quantitative research denotes the suitability, meaningfulness, and usefulness of the deductions, propositions, and conclusions made by the researcher on the basis of the study data gathered from the field (Creswell, 2002). Internal validity, which is concerned with guaranteeing the soundness of an evaluation, has been achieved by (1) employing a broad spectrum of content rather than a constricted one, (2) utilizing appropriate sampling technique to meet the needs of the study, (3) accentuating important material, and (4) utilizing a validated and reliable instrument for purposes of collecting data (Sekaran, 2006). The external validity of the present study findings has been attained by enrolling an adequate sample size to ensure that the results can be easily generalized to other study contexts.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical concerns were noted during the data collection phase and addressed as they arose. Necessary approval to undertake a research study involving human subjects was sought from the University and filled out as required. A letter seeking permission from the Hotel’s management to collect data from the facility’s workforce was also prepared, dispatched, and approved. An informed consent form with explicit details regarding the nature and purpose of the study, along with an exposition of the rights of participants (e.g., right to informed consent, right to withdraw from the research process, right to privacy), was prepared and dispatched to the field for the participants’ perusal and signing. Lastly, returned questionnaires were numerically kept in a protected user file to protect the anonymity of participants.

Data Analysis

Since the present quantitative study utilizes a descriptive research (survey research) design, the researcher has made use of a statistical software program known as SPSS for Windows for purposes of analyzing quantitative data. In summary, the analysis has undergone various steps, including data coding, entry, cleaning, analysis, and interpretation of results. The researcher has largely relied on descriptive statistics and/or univariate methodology to analyze data, get frequency distributions and cross-tabulations, and present them in various formats including normal text, mean scores, pie-charts as well as bar graphs, with the view to demonstrate work commitment issues affecting permanent and temporary workers in the hotel industry.

Results and Discussion

Introduction

The present study is hinged on the urgent need for organizations within the services industry in general, and the hotel sector in particular, to develop and implement strategies and interventions that would make employees – permanent or temporary – become more committed to their work. More importantly, organizations in this sector need to develop focused strategies on how to indulge temporary workers since labor dynamics point out to an increased reliance on this cluster of workers as opposed to permanent staff. Towards the realization of the study’s broader aim of analyzing the work commitment levels for permanent versus temporary employees working in a five-star hotels located in China, a survey was conducted on a sample of 80 participants drawn from the hotel. It is important to note that the researcher received 54 duly filled questionnaires, representing a 67.5% response rate. Overall, 28 permanent and 26 temporary workers responded, representing 51.9% and 48.1% of the total responses, respectively.

Statement of Results

The major highlights of the study results are not only interesting but informative too, although they are generally in line with the expectations of the researcher. An analysis of demographic information demonstrates that organizations within the hotel sector employ a young workforce, with the majority of the sampled participants (68.2%) acknowledging there are yet to celebrate their 30th birthday in both clusters – permanent and temporary. 17 (60.7%) in the permanent job status and 12(46.2%) in the temporary job status are male, while the rest of the distribution comprises female employees. A substantial number of core employees (56%) have been inactive employment for a period not less than five years, while only a handful of temporary workers (26%) report working for the hotel for a cumulative period totaling one year. An analysis of the participant’s educational status demonstrates that slightly above two-thirds of the core staff (67.8%) has attained university-level education, while all temporary workers have graduated from middle-level colleges offering courses in hotel and hospitality management. Below, the results are presented based on the study’s objectives and key research questions.

Relationship between Job Status & Work Commitment

Descriptive means are employed to demonstrate how core and temporary workers rate some underlying issues thought to influence work commitment, including clarity of goals and objectives, ability to manage and control work, knowledge and practical skills, job experience, management support, and responsiveness, as well as self-discipline. It is important to note that a 5-point Lickert-type scale has been used to rank the responses, with 1 representing “strongly agree” and 5 representing “strongly disagree.” As demonstrated in the Table next page, temporary workers show less commitment as their level of agreement with core variables thought to positively influence work commitment are substantially lower in comparison to the core workers, and there is a similar, but marginally significant, outcome for continuance commitment.

A major finding demonstrated in the table is that most temporary workers strongly agree that they experience high levels of job uncertainty. Equally, they strongly agree that they do not get what they deserve from the organization. Overall, it can be demonstrated from the table that job status directly influences important variables related to work commitment, with core staff identifying more with variables that positively influence work commitment while temporary workers identify more with variables thought to hinder the progression and growth of work commitment. This finding has important ramifications for the hotel industry.

Table 1: Descriptive Means for Work Commitment Variables depending on Job Status.

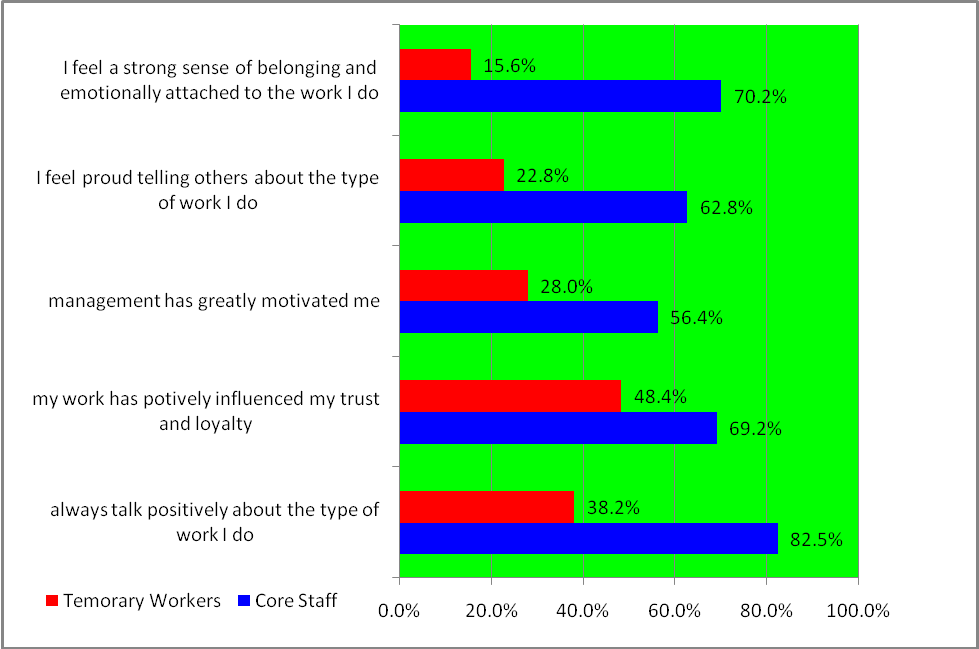

Frequency distributions have also been run on important work-related characteristics thought to influence work commitment, with results demonstrating that job status is an important predictor to these characteristics. For instance, eight in every 10 core employees (82.5%) always talk positively about the kind of work they do for the hotel, while in excess of two-thirds (69.2%) think that the kind of work they do for the organization has positively affected their trust and loyalty to the organization, and more than half (56.4%) feel the hotel’s management has done much in terms of motivating them to offer their best. However, the situation is different for temporary workers, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Job Status, Work Commitment & Turnover Intentions

With regard to the interrelationship between job status, work commitment and turnover intentions, temporary workers demonstrate more exit intentions and other negative actions considered to be counterproductive to organizational efforts made toward work commitment. Descriptive means employed to demonstrate how core and temporary workers rate various statements related to quit intentions and disloyal OCB confirm that indeed job status is indeed a predictor to quit intentions, job neglect, and disloyalty. Table 2 samples some of the results of how the workers either agreed or disagreed with the statements. Again, it should be noted that a 5-point Lickert-type scale has been used to rank the responses, with 1 representing “strongly agree” and 5 representing “strongly disagree.”

Table 2: Descriptive Means for Job Status & Quit Intentions.

Organizational/Employee Behaviors & Triggering Issues

All the variables included in the questionnaire instruments to evaluate organizational and employee behaviors as influenced by job status and work commitment demonstrate that temporary workers show less positive behaviors and more negative behaviors towards their work than core employees do; that is, they display less voice and loyalty, and more exit intentions, labor market activity, as well as feelings of neglect. Monetary and non-monetary rewards and incentives, for instance, have been found to be important determinants to work commitment and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Employees who feel satisfied with the reward system set by the hotel facility demonstrate less exit and neglect, and more positive OCB, voice and loyalty. Again, there is a marked difference between core and temporary workers with regard to organizational rewards and incentives, with more core staff (72.4%) saying they are satisfied with the reward/incentive system while two-thirds (66.8%) of temporary workers register dissatisfaction.

Opportunity for career growth and development has also been found to be an important determinant of work commitment and OCB. Again, majority of core staff (72.2%) feels that the job presents opportunities for career progression, and this makes them more loyal and committed to their work. However, only 5 (19.2%) temporary workers feel their current job presents an opportunity for career growth and personal advancement. The absence of this opportunity for temporary workers affect their loyalty to their work and organization, increase quit intentions if granted the opportunity to work for another organization, and adversely affect their job morale and motivation.

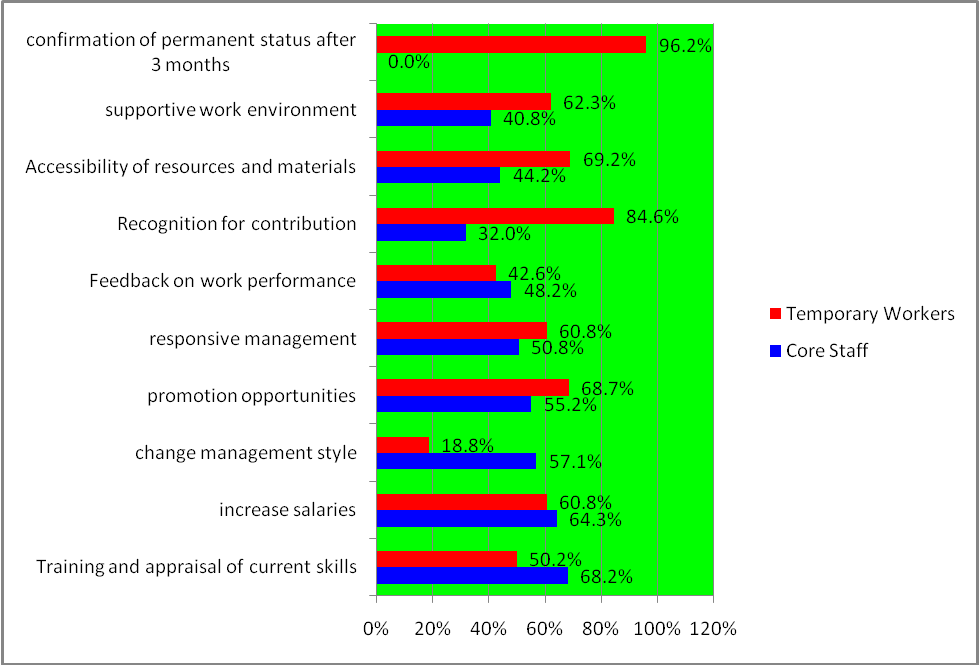

In issues that need to be done to improve work commitment, slightly over two-thirds (68.2%) of the core staff feels the organization needs to increase training and appraisal of current skills, 18(64.3%) feels the management needs to enhance salaries, while 16(57.1%) are of the opinion that a change of management style is needed to spur work commitment. An important finding for the present study is that most temporary workers do not view the confounding issues to work commitment using the same lens as the core staff do. For instance, 25(96.2%) of the temporary workers feel that their status need to be changed to ‘permanent staff’ upon providing services to the organization for a period of up to three months, while 22(84.6%) feel they need to be recognized by management for services provided and 18(69.2%) feel they need to have more access to resources and resources to do the job. The rest of the distribution is shown in Figure 2.

As demonstrated in the figure above, the three most important issues that need to be addressed to spur work commitment among core staff include (1) provision of training opportunities and appraisal of current skills, (2) increasing salary packages, and (3) enhancing promotion opportunities. Similarly, the three most important issues for temporary workers include (1) conformation of permanent status upon working for three months, (2) recognition for contribution, and (3) provision of promotion opportunities.

Discussion

The initial objective of the present study is to critically analyze the work commitment for permanent versus temporary workers at Jing Jiang Tower Hotel, Shanghai. In line with Kini and Hobson (2002) meta-analyses cited in Crawford and Hubbard (2008), the findings demonstrate that work commitment is not only predicted by job status variables, including job security, payment and bonuses as well opportunities for further training and career progression, but also shares a relationship with intrinsic work satisfaction variables, goal-setting behavior and job involvement, intrinsic total quality initiatives, intention to quit, and organization-based self esteem. The findings are conclusive in demonstrating how temporary workers feel emotionally detached from some key variables thought to be instrumental to work commitment and quit intentions. For instance, most temporary workers agree they have contemplated leaving due to job insecurity, have no problem working for another organization, not mentioning that they feel workers in other organizations have better work environments and reward packages. In line with the affective commitment literature, these workers have neither identified nor internalized the explicit self-determined motivations that would enable them become more committed to their work (Steenbergen & Ellemers, 2009).

More importantly, and in line with the extant literature, the results of the present study demonstrate that job status (either permanent or temporary) indeed influence attitudinal and behavioral responses towards the type of work an individual does for the organization. This finding implies that people who perform the same type of jobs within the hotel setting, but who have divergent contracts with the organization regarding the type of work they do, differ substantially in their attitudes and behavior towards the work. The psychological contract literature explains these divergences as emanating from (1) how the worker is treated by the employer, and (2) what the worker puts into the job (Raulapati et al., 2010). Further analyses demonstrate that the concept of ‘mutual exchange’, which is an intrinsic determinant of work commitment, is lacking in the interactions between the hotel’s management and temporary workers, but is present in the interactions between the management and core staff. This finding reinforces the assertion by Cohen (2011), who acknowledges that the type of psychological contract, as well as infringements of such contract, influence workers’ attitudes and behaviors, including commitment, performance, productivity, turnover, and extra-role performance.

In the present study, it is clear that temporary workers demonstrate relatively low affective commitment constructs (e.g., I enjoy discussing the organization with people outside the hotel; I feel I am emotionally attached to this organization; I feel a strong sense of belonging, etc) to their work, not mentioning that they exhibit less constructive, and more destructive organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) when compared to employees hired on a permanent basis. This orientation implies that temporary workers are yet to accept and internalize the goals and objectives set by the organization, and therefore are not willing to neither exert effort on the organization’s behalf, nor demonstrate a strong attachment to the party (Johnson et al., 2010).

The findings of the present study are also clear that majority of core staff demonstrates relatively high continuance commitment constructs (e.g., see myself doing the same type of work five years to come; I would be very happy spending the rest of my career life in this organization, etc), as well as normative commitment variables (e.g. loyalty to the organization; commitment and responsiveness demonstrated by management, etc). It is imperative to note that temporary workers score poorly in these constructs, implying that there exists a relationship between favorable continuance and normative work commitment constructs on the one had, and work commitment behaviors on the other hand. More importantly, the current findings demonstrate that job status is a predictor of whether these constructs attain positive or negative work-related and organizational outcomes. Available literature demonstrates that high continuance and normative commitment variables are positively correlated to improved worker performance, sustainable OCB, as well as diminished turnover intentions (Jafri, 2011). Equally previous research shows that the nature of current employment trends, typified by an increase in temporary employment (Bulut & Culha 2010) and loss of job security (Carmeli et al 2007), have not only resulted in a redefinition of career expectations and the nature of the employment relationship, but is increasingly triggering psychological contract breaches, resulting in numerous adverse job-related behaviors for the organization such as diminished commitment, reduced citizenship behavior, lowered worker trust, as well as enhanced likelihood to leave the organization (McDonald & Makin 2000; Jafri 2011).

Lastly, the findings of the present study demonstrate clear differences between temporary and permanent workers in their choice of issues that need to be addressed to enhance work commitment. When evaluated under the prism of reciprocity theory, the discordance of options along job status implies that this theory works more for core staff than it does for temporary workers. Previous research findings have demonstrated that in organizational as well as work-related contexts, positive treatment from an employer in the form of respect, provision of favorable work environment, consideration, or financial and non-financial resources afforded to the worker should be reciprocated in the form of positive attitudes and work-oriented effort (Biggs & Swailes 2006). This theory is therefore effective in demonstrating the reasons why core staff develop high levels of affective, continuance and normative commitment towards their work.

Conversely, the organization support theory effectively demonstrates why temporary workers posses extremely low levels of affective, continuance and normative commitment towards their work as demonstrated by the findings from the present study. This theory, according to extant literature, acknowledges that workers hold perceptions about how much their employer values their contribution (Biggs & Swailes 2006), as well as how the employer care about them as individuals; that is, whether the employer is concerned about the workers’ sense of (dis)satisfaction with some characteristics of their working life (Cohen 2011). From the study findings, it is clear that the hotel’s management does little to demonstrate consideration and recognition of temporary workers contribution, not mentioning that it is less concerned in improving the working conditions of temporary workers, leading to extremely low levels of work commitment and subsequent turnover. These findings are extremely important in designing various interventions to improve work commitment, outlined in the following section.

Conclusions & Recommendations for Practice

Conclusions

The present study is, to a large extent, informed by the need to learn more about the relationship between the various constructs thought to influence work commitment, with the view to assist organizations within the services sector to develop a framework through which they can make use of temporary workers and still remain competitive and productive. The exposition of current management literature has demonstrated that many organizations are moving away from overreliance of core staff towards utilization of temporary workers, not only to cut down on mounting labor costs but also maintain flexibility and effectively manage temporary absence of core members of staff (Van Breugel et al 2005).

Several conclusions can be drawn from the findings. First, it is clear that the hotel sector is yet to develop effective policies and strategies aimed at triggering work commitment behaviors among temporary workers. However, core members of staff are stimulated towards work commitment through provision of adequate training opportunities, endowment with capacities to manage and control own work, demonstrated experience on the job, reinforcement of organizational goals and objectives, as well as exposure to a supportive and responsive management. It is clear that these policies/strategies have been successfully used to enhance affective, continuance and normative commitment for core staff, but not for temporary workers.

The second conclusion is that job status is a strong predictor of work commitment because temporary workers have been found to neither identify nor internalize the explicit self-determined motivations that would enable them become more committed to, and involved in, their work. The third conclusion is that job status is a predictor of organizational citizenship behavior as well as quit intentions. Temporary workers have been found to demonstrate less constructive and more destructive OCB when compared to core staff, a scenario that is inherently tied to relatively low affective commitment among people who work on temporal basis. Due to prevalent inadequacies in their affective, continuance and normative constructs, it has been found that temporary workers are more likely to redefine their career expectations, experience diminished commitment, exhibit negative or undesirable OCB, as well as demonstrate an elevated likelihood to leave the entity.

The fourth conclusion relates to the obstacles to the realization of work commitment among permanent and temporary workers. It is clear from the findings that the two groups are affected by completely different obstacles, with temporary workers highlighting management issues (unsupportive and unresponsive management), lack of training opportunities, high level of job uncertainty and limited opportunities for upward career mobility, while permanent workers highlight issues related to salaries and remuneration. In essence, it can be surmised that the obstacles that hinder temporary workers to achieve work commitment efficiencies are largely operational, while those hindering core staff are largely personal.

The last conclusion is in regard to the issues that need to be addressed to enhance work commitment for permanent and temporary workers. From the study findings, the three most important issues that need to be addressed to spur work commitment among core staff include (1) provision of training opportunities and appraisal of current skills, (2) increasing salary packages, and (3) enhancing promotion opportunities. Similarly, the three most important issues for temporary workers include (1) confirmation of permanent status upon working for three months, (2) recognition for contribution, and (3) provision of promotion opportunities. These divergent needs can only be achieved by applying the following recommendations.

Recommendations for Practice

Organizations doing business within the hotel industry need to consider the following if they are to make effective and efficient use of available labor resources in the form of temporary workers:

- Introduce programs and policies that will ensure temporary workers identify and internalize the explicit self-determined motivations that would enable them to become more committed to their work. Introducing policies that will ensure the availability of worker training programs, opportunities for career advancement and growth and conducive working environments is a step in the right direction, especially in enhancing work commitment and positive organizational behavior while at the same time curtailing turnover;

- Management needs to be more proactive in providing support and feedback to temporary workers to provide them with an avenue through which they become well versed with the goals and objectives of the organization, as well as demonstrate effective capacity to control and manage their own work;

- Management needs to work on spurring the affective, continuance and normative commitment constructs among temporary workers not only to enhance their productivity and performance, but also to constrict counterproductive behavior, disloyalty and quit intentions. This can only be achieved by embracing positive treatment of all the workers regardless of job status;

- Training resources should be provided to temporary workers so that they posses the skills needed to be effective and productive on the job, and;

- Workers should be remunerated adequately for their input as such a gesture urges them to reciprocate in the form of developing positive attitudes and work-oriented effort.

Study Limitations

The present study has been limited by financial constraints and time resources, forcing the researcher to use a small sample size. As such, it will be difficult to generalize the findings to other hotels doing business within the services sector. Additionally, it has not been possible to collect primary field data by directly surveying the participants due to the mentioned limitations. It is generally felt that one-on-one interactions with participants could have resulted in data that were rich in context and scope.

Reference List

Balnoves, M & Caputi, P 2001, Introduction to quantitative research methods: An investigative approach, Sage Publications Ltd, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Biggs, D & Swailes, S 2006, ‘Relations, commitment and satisfaction in agency workers and permanent workers’, Employee Relations, vol. 28 no. 2, pp. 130-143.

Bryman, A & Bell, E 2007), Business research methods, 2nd ed, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bulut, C & Culha, O 2010, ‘The effects of organizational training on organizational commitment’, International Journal of Training & Development, vol. 14 no. 4, pp. 309-322.

Burgess, J & Connell, J 2006, ‘Temporary work and human resources management: Issues, challenges and responses’, Personnel Review, vol. 35 no. 2, pp. 129-140.

Carmeli, A, Elizur, D & Yaniv, E 2007, ‘The theory of work commitment: A facet analysis’, Personnel Review, vol. 36 no. 4, pp. 638-649.

ChinaTour.Net 2010, Shanghai Jin Jiang Hotel, Web.

Chon, K, Sung, K & Yu, L 1999, The international hospitality business: Management and operations, Routledge, New York, NY.

Cohen, A 2011, ‘Values and psychological contracts in their relationship to commitment in the workplace’, Career Development International, vol. 16 no. 7, pp. 646-667.

Crawford, A & Hubbard, SS 2008, ‘The impact of work-related goals on hospitality industry employee variables’, Tourism & Hospitality Research, vol. 8 no. 2, pp. 116-124.

Creswell, JW 2002, Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative approaches to research, Merrill/Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

De Cuyper, W & De Witte, H 2007, ‘Job insecurity in temporary versus permanent workers: Association with attitudes, wellbeing, and behavior’, Work & Stress, vol. 21 no. 1, pp. 65-84.

De Gilder, D 2003, ‘Commitment, trust and work behavior: The case of contingent workers’, Personnel Review, vol. 32 no. 5, pp. 588-604.

Elizur, D 1996, ‘Work values and commitment’, International Journal of Manpower, vol. 17 no. 3, pp. 25-30.

Freund, A & Carmeli, A 2003, ‘An empirical assessment: reconstruct model for five universal forms of work commitment’, Journal of Managerial Psychology, vol. 18 no. 7, pp. 708-725.

Gonzalez, J & Garazo, T 2006, ‘Structural relationships between organizational service orientation, contract employee job satisfaction and citizenship behavior’, International journal of Service Industry Management, vol. 17 no. 1, pp. 23-50.

Haden, SSP, Caruth, DL & Oyler, JD 2011, ‘Temporary and permanent employment in modern organizations’, Journal of Management Research, vol. 11 no. 3, pp. 145-158.

He, Y, Lai, KK & Lu, Y 2011, ‘Linking organizational support to employee commitment: Evidence from hotel industry of China’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 22 no. 1, pp. 197-217.

Jacobsen, DI 2000, ‘Managing increased part-time: Does part-time work imply part-time commitment’, Managing Service Quality, vol. 10 no. 3, pp. 187-201.

Jafri, H 2011, ‘Influence of psychological contract breach on organizational commitment’, Synergy, vol. 9 no. 2, pp. 19-30.

Jin Jiang Tower 2012a, History, Web.

Jin Jiang Tower 2012b, About Jin Jiang Tower, Web.

Johnson, RE, Chang, CH & Yang, LQ 2010, ‘Commitment and motivation at work: The relevance of employee identity and regulatory focus’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 35 no. 2, pp. 226-245.

Klein, H.J, Molloy, JC & Brinsfield, CT 2012, ‘Reconceptualizing workplace commitment to redress a stretched construct: Revisiting assumptions and removing confounds’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 37 no. 1, pp. 130-151.

Lam, T, Pine, R & Baum, T 2003, ‘Subjective norms: Effectiveness on job satisfaction’, Annals of Tourism Research, vol. 30 no. 1, pp. 160-177.

Lewis, T 2011, ‘Assessing social identity and collective efficacy as theories of group motivation at work’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 22 no. 4, pp. 963-980.

McDonald, DJ & Makin, PJ 2000, ‘The psychological contract, organizational commitment and job satisfaction of temporary staff’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, vol. 21 no. 2, pp. 169-186.

McKeown, T 2003, ‘Commitment from a contractor workforce?’, International Journal of Manpower, vol. 24 no. 2, pp. 169-186.

Meldrum, JT & McCarville, R 2010, ‘Understanding commitment within the leisure service contingent workforce’, Managing Leisure, vol. 15 no 1/2, pp. 48-66.

Meyer, J & Allen, N 1997, Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Miller, J, Walker, K, Drummond, K & Hoboken, M 2002, Supervision in the hospitality industry, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken.

Nath, R & Raheje, R 2001, ‘Competencies in hospitality industry’, Journal of Services Research, vol. 1 no. 1, pp. 25-35.

Phillips, PP & Starwaski, CA 2008, Data collection: Planning for and collecting all types of data, Willey & Sons, London.

Raulapati, M, Vipparthi, M & Neti, S 2010, ‘Managing psychological contract’, IUP Journal of Soft Skills, vol. 4 no. 4, pp. 7-16.

Rosendaal, BW 2003, ‘Dealing with part-time work’, Personnel Review, vol. 32 no. 4, pp. 474-491.

Sekaran, U 2006, Research methods for business: A skill building approach, 4th ed, Wiley-India, Mumbai.

Singh, V & Vinnicombe, S 2000, ‘What does commitment really mean?: Views of UK and Swedish engineering managers’, Personnel Review, vol. 29 no. 2, pp. 228-254.

Van Breugel, G, Van Olffen, W & Olie, R 2005, ‘Temporary liaisons: The commitment of ‘temps’ towards their agencies’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 42 no. 3, pp. 539-566.

Van Steenbergen, EF & Ellemers, N 2009, ‘Feeling committed to work: How specific forms of work commitment predict work behavior and performance over time’, Human Performance, vol. 22 no. 5, pp. 410-431.

Yousef, DA 1998, ‘Satisfaction with job security as a predictor of organizational commitment and job performance in a multicultural environment’, International Journal of Manpower, vol. 19 no. 3, pp. 184-194.

Appendix: Data Collection Instrument

Hello! My name is ……………………..from ……………………………University. This data gathering exercise is informed by the need to fulfill the academic requirements set by the university towards the conferment of a Bachelor of Science degree in Hotel and Hospitality Management, implying that data provided by you – the participant – will be used for academic reasons only. I therefore want to take this opportunity to kindly request for your input in completing this survey to help the researcher develop a better understanding on the issues related to work commitment for both permanent and temporary workers at the hotel.

Important

The survey will take between 30 and 35 minutes to complete, and is entirely voluntary. The researcher guarantees that all the information provided by you (the participant) will be kept and used in strictest confidence, and for the purpose initially intended.

Section A: General Information

- Age……………………………….

- Gender

- Male

- Female

- Employment type

- Permanent

- Temporary

- Length of service Less than 6 months

- >6 months – one year

- > one year – three years

- > three years – five years

- >five years – seven years

- >seven years – ten years

- 10 year +

- Highest level of education Primary

- Secondary

- Middle-level colleges

- University

- Masters

- PhD

Section B: Work-Related Characteristics & Behavior

- Please indicate the level to which you either agree or disagree with the following work-related statements (tick where appropriate; 1= strongly agree, 5= strongly disagree)